Thomas Hart Benton was born on March 14, 1782, in Harts Mill, (near Hillsboro) North Carolina. As a young man, he studied to follow his fathers profession of law until called home by his widowed mother to manage the family estate. Like many other ambitious young Southerners of his day, Benton was attracted to the opportunities and excitement of the raw frontier state of Tennessee. In 1799, he moved his family to a 40,000 acre tract near Nashville, bequeathed him by his father, and set to work building a plantation, roads, mills, school and meeting houses, and other buildings necessary to the town he founded there. Meanwhile, he finished his studies, was admitted to the Tennessee bar, and was soon active in state politics and military affairs. He attracted the attention of Andrew Jackson, even then one of the most powerful men in Tennessee. At the outset of the War of 1812, General Jackson appointed Benton his aide-de-camp, with the rank of lieutenant colonel. The young colonel saw no military action, however. His political connections, sharp mind, and fluent speech made him more valuable to Jackson at the nation's capital, smoothing over the General's differences with the federal government. Already impatient at the lack of opportunity for military glory, Benton was enraged at the news of an insult offered his brother Jesse by Andrew Jackson himself. The two quarreled bitterly; Jackson publicly threatened to horsewhip Benton. The hot tempered Benton exploded, and the affair climaxed in a brawl in Nashville's City Hotel. As Theodore Roosevelt put it: "The details were so intricate that probably not even the participants themselves knew exactly what had taken place, while all the witnesses impartially contradicted each other and themselves. At any rate, Jackson was shot and Benton was pitched headlong downstairs, and all the other combatants were more or less damaged." While Jackson was carried off for medical attention, Benton seized the General's sword and ceremoniously broke it over his knee. Shortly thereafter, the Benton brothers beat a hasty, but prudent, retreat to Missouri.

The move to Missouri was a turning point in Benton's career. In Tennessee, he chafed at his role of second to "Tennessee's first citizen"; in Missouri, he would be the first citizen. By 1815, he was settled in St. Louis, active in law and politics, and editor of The Missouri Enquirer. The force, energy, and earnestness of his oratory won him a wide following in the territory. Upon the famous Missouri Compromise of 1820, admitting Missouri to the Union as a state, Benton was elected the first U.S. Senator. He would subsequently be re-elected to serve five consecutive terms, the first man to serve 30 years in the U.S. Senate. For most of those years, he virtually controlled Missouri, was one of the most powerful and influential men in the country, and "grand old man" of the Democratic Party. The development of the West was his greatest passion, and he worked unceasingly on all projects important to western interests. Benton was famous for his efforts to establish a liberal system of land distribution that would discourage speculators but enable honest settlers to purchase public lands at low prices. He championed the pony express, the telegraph, interior highways, the opening of the Oregon and Santa Fe trails, and transcontinental railroads. When Andrew Jackson became President, the two men forgot their old quarrel and joined together in a crusade against monopolies and eastern capitalists. Benton steadfastly supported hard currency and so acquired his popular nickname, "Old Bullion".

Most importantly for the Pacific Northwest, Benton worked throughout his years in the Senate to realize his vision of a United States stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific. He favored the annexation of Texas, continually agitated for a settlement of the Canadian-U.S. border on the most favorable terms possible to the United States, and was the first to introduce in the Senate a bill demanding exclusive American control of the Oregon country, A treaty of 1818 allowed the U.S. and Great Britain equal rights and joint occupancy of the Pacific Northwest. From 1820 on, however, Benton repeatedly demanded the treaty be abrogated and a definite boundary be set – if not at the famous 54'40", at least at the 49th parallel. In 1846, his efforts met with success, and the United States laid claim to all of the Pacific Northwest south of the present boundary. At a time when most Americans could see little value or future promise in this region, Benton passionately championed its potential. Even the arid lands of what would one day be called Benton County were glorified in his grand oratory. Speaking in the Senate on May 22, 1846, Benton described the country at the mouths of the Yakima and Snake Rivers :

"In some respects, it is a desert – barren of wood – sprinkled with sandy plains – melancholy under the somber aspect of the gloomy artemisia – and desolate from volcanic rocks, through the chasms of which plunge the headlong streams. But this desert has its redeeming points – much water, grass, many oases, mountains capped with snow, to refresh the air, the land, and the eye – blooming valleys – a clear sky, pure air, and a supreme salubrity. It is home of the horse found there wild in all the perfection of his first nature – beautiful and fleet – fiery and docile – patient, enduring, and affectionate. The country that produces such horses must also produce men, and cattle, and all the other animals; and must have many beneficient attributes to redeem it from the stigma of desolation."

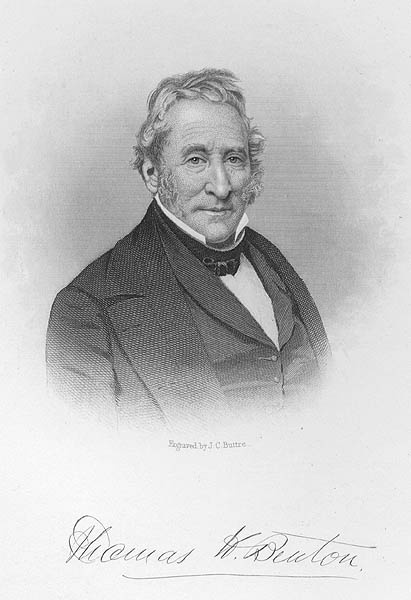

Benton died in Washington D.C. on April 10, 1858 at the age of 76.

Remembering Benton's great services to the West, generations of Westerners named counties, towns, avenues and buildings to honor their champion. It was hardly surprising that Eastern Washingtonians would follow this time honored practice. In 1901, Nelson Rich, of Prosser, proposed a new county to be created from the eastern sections of Yakima and Klickitat counties. The plan met with such opposition that it never came to a vote. In 1903 a similar proposal met with a little more success, but the bill was defeated in the legislature. Finally, in 1905, the new county was created and named in honor of Thomas Hart Benton. The bill from the legislature establishing the county and defining its boundaries was approved by Governor Albert I. Mead on March 8, 1905, and the official proclamation was issued June 17, 1905.