JONES, John Percival, 1829-1912

Senate Years of Service : 1873-1895 ; 1895-1901 ; 1901-1903

Party : Republican ; Silver ; Republican

JONES, John Percival, a Senator from Nevada ; born at ‘The Hay,’ Herefordshire, England, January 27, 1829 ; immigrated the same year to the United States with his parents, who settled in the northern part of Ohio ; attended the public schools in Cleveland, Ohio ; moved to California and engaged in mining and farming in Trinity County ; sheriff of the county ; member, State senate 1863-1867 ; moved to Gold Hill, Nev., in 1868 ; engaged in mining ; elected as a Republican to the United States Senate in 1873 ; reelected in 1879, 1885, 1891, and 1897 and served from March 4, 1873, to March 3, 1903 ; declined to be a candidate for reelection ; chairman, Committee to Audit and Control the Contingent Expense (Forty-fourth and Forty-fifth Congresses, and Forty-seventh through Fifty-second Congresses), Committee on Epidemic Diseases (Fifty-third through Fifty-seventh Congresses) ; resumed his former business activities ; retired to his home in Santa Monica, Calif.; died in Los Angeles, Calif., November 27, 1912 ; interment in Laurel Hill Cemetery, San Francisco, Calif.

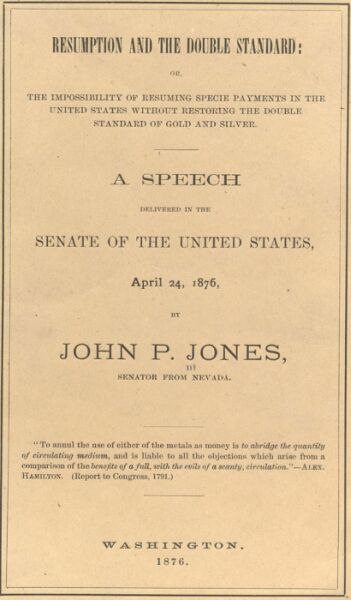

SPEECH

OF

HON. JOHN P. JONES.

The Senate, as in Committee of the Whole, having under consideration the bill (S. No. 263) to amend the laws relating, to legal tender of silver coin ; the pending question being on the amendment of Mr. Bogy to the amendment reported by the Committee on Finance—

Mr. JONES said :

Mr. PRESIDENT : The act of February 12, 1873, now incorporated in title 37 of the revised Statutes, an act which, under the guise of regulating the mints of the United States, practically abolished one of the precious metals, was a grave wrong ; a wrong committed no doubt unwittingly, yet no less certainly, in the interest of a few plutocrats in England and in Germany and as certainly in the interest of the entire pagan and barbarian world ; a wrong upon the people of the United States and of the whole civilized globe ; a wrong upon industry, upon the natural tendency of wealth toward equalization, upon the liberties of peoples which are born out of the effects of such equalization of wealth, upon every aspiration of man which depends for its realization upon the development of those liberties.

The act alluded to practically abolished one of the precious metals as money, the one chiefly produced in this country, the one chiefly consumed in the semi-civilized countries of Asia, and the one which at the date of its abolition and under the time-honored laws that previously prevailed was becoming, as it has since become, the more available metal of the two in which to transact exchanges and liquidate debt.

Under the act of April 2, 1792, both silver and gold coins—dollars or their multiples—were made a legal tender in this country for the payment of debts to any amount, at the rate of 15 in weight of silver to 1 of gold. This co-ordination of silver and gold is called the double standard. A similar arrangement existed in the other countries of the civilized world ; the relation fixed by law in those countries being either 15½ or 16 for 1. A few countries had a single silver standard, but no country, until 1816, had a single gold standard. In this country, up to 1853, the Government defrayed the expense of manufacturing coins, while in Europe, except in England, where the coinage is also free, the owners of the bullion offered for coinage are assessed with a charge for manufacture. Thus, under our old laws, and, as I shall endeavor to show under the requirements of the Constitution, the owner of either gold or silver bullion had the right, if the Government chose to coin any money at all, to have his bullion coined free of charge ; and once coined it became a legal tender to any amount for the payment of debts, whether the bullion was of gold or silver.

Although free coinage only dates from that era of other free institutions, the American Revolution, the double standard of money has existed since the remotest past. This arrangement, so far as we know, has existed everywhere and forever, notwithstanding the fact that at certain periods silver, as compared with gold is yielded by the, mines in deficit of the world’s consumption, while at other periods gold, as compared with silver, is yielded in deficit. At the period in question—that is to say, from 1792 until the effects of the discovery of the Russian, the American, and the Australian gold mines were felt—gold was produced in deficit ; and by reason of this fact, silver, at the legal rate of 15 for 1, was the cheaper metal in which debts could be discharged. Accordingly, silver was used for this purpose in this country to the exclusion of gold, the debtor being at liberty to tender either metal he thought proper. By the act of June 28, 1834, this relation was changed to 16.00215 for 1, and by that of January 18, 1837, to 15.98837 for 1, in both cases substantially 16 for 1, at which figure it stood up to February 12, 1873.

When the great Russian mines threw their auriferous products upon the markets, gold became the cheaper metal at the legal relation of, then, substantially 16 for 1 ; and our silver legal-tender dollar disappeared from circulation. Nevertheless this coin was not abolished, and the privilege of free coinage and the right to tender the silver dollar for debt remained the same as before. The pivotal point of this event was the period of depression which followed the panic of 1837. About the period of 1863-’73 another great change in the relative production of the metals occurred, and gold instead of silver was produced inadequately. This occurrence began to operate about the year 1865, when the world’s product of gold had attained its maximum. However, this change did not appear to have been felt until some few years afterward, when its influence upon the relative value of the metals was greatly intensified by the threatened demonetization of silver by the German Empire and its partial actual demonetization by other European states. In 1855 the relation of gold to silver in the London market was 1 to 15.33 ; in 1872 it was 1 to 15.63. This is, considered the pivotal point of the change, because the legal relation of gold and silver in most of the countries of Europe was 15.50. In 1874 the London quotation rose to 16.15, and at the present moment it is about 17.60, a relation which shows that the value of gold to silver is about 10 per cent. above that fixed by our law of 1792, as amended by the acts of 1834 and 1837.

The double standard, or the legal establishment of a fixed relation between silver and gold at the calculated center of their mutual oscillations, is not the unnatural and one-sided measure which some recent writers have supposed it, but the fulcrum of a just balance whose scales are alternately depressed. Both gold and silver are indispensable, and needed for the coins of the world—gold for large payments, silver for large and small ones ; and it will be found that in great commercial countries both gold and silver are needed. Outside of the great bulk of mankind who use either one or both of those metals for money, there is a small number on the one side who are too poor even to use silver, and a small number on the other who are too rich even to use gold. The very poor employ copper ; the very rich paper notes and checks. In both of these cases the substitutes for gold or silver are not real money, but representatives. Copper coins are never of full weight, and are called tokens ; paper instruments are intrinsically worthless, and are merely promises, direct or remote, to pay money of gold or silver. To the mass of mankind gold and silver are both indispensable for the purpose of exchange, and these two metals constitute the money of the world.

Were their quantitative relation unknown or changing always in one direction—for example, was silver always becoming cheaper or gold dearer—a double standard would prove inconvenient. But such is not the fact. The relation of these metals to one another for many centuries has been very constant, the pivotal point being 15½, and the oscillations—until within the past year, and chiefly in consequence of the demonetization of silver in Germany—quite inconsiderable. This constancy of relation is due to the stock of precious metals already in the world, to the proportion of gold to silver needed for the world’s convenience, to the vicissitudes of production, to the occurrence of gold and silver in the same ore matrices, and to other physical circumstances which will be adverted to hereafter.

Without perhaps fully knowing the causes of it, but assured from long experience of its continuance, nations have hitherto been satisfied, in their search for an approximatively immutable measure of values, to adopt the double standard, which, constituting a measure, now of gold and then of silver, nevertheless served to measure with constant efficiency any given quantum of labor or its products ; just as a peck measure, whether constructed of gold or silver, will measure always just one peck, or as nearly so as the different effects of temperature upon the two metals will permit.

This is what has been understood in all ages by the double standard, and this is what our forefathers understood by it when they fixed it, first at 15 and then at 16 to 1, a wise and far-sighted mean between the market relation of silver and gold for two generations previous to and after the date of the three enactments which they transmitted to us.

In case no such amendments had been made to the bill now before the Senate, as have been offered by the Senator from Missouri, it was my intention to offer a simple amendment to restore the double standard of the United States, and to base its system of money upon the money of the world, upon which it is now not based. To accomplish this object it was suggested that I might, with, perhaps, greater assurance of success, attempt it by the same indirection which practically destroyed the double standard. But this course might indicate a lack of confidence in the strength of the amendments or the sufficiency of those arguments of sound policy and expediency upon which they rest.

The wrong which has been done can never be fully undone by indirection. The undoing must be as open and explicit as the doing was indirect and implied.

To secure this result nothing more is needed than that the history of the precious metals shall be recalled ; that history which is so full of happiness and misery, of affluence and of poverty, of ease and of hardship ; that history in part of which my life has been passed, and which has therefore impressed itself upon me not only by study but partly also by practical experience.

The flood of light which this history throws upon the subject, while it will establish the necessity and importance of the double standard, will also serve to allay any fears that may be entertained on the one hand as to the observance of specie contracts, or on the other as to the due recognition of paper credit as an economical and essential element of the currencies of modern nations.

As this history, be it ever so briefly recounted, is of some length, and as the conclusions to which I desire to direct attention are somewhat numerous, I deem it best at the outset to summarize what I propose to say on this subject.

First. I propose to set forth the function and nature of money, the various substances which have been used for money, and the characteristics which during fifty centuries of trials have induced the precious metals as a duality to be always resorted to for this purpose throughout the world.

Second. I propose to show that the use of money and the preference of the precious metals for money were both natural and voluntary acts, not due to law or edict, and that, therefore, money is of right, and ought to be, free and untrammeled by any regulations except of a kind specified.

Third. I propose to trace the stock of the precious metals in the world from the earliest period for which we have authentic data, to show its mutations down to the present time, and the political, industrial, and social phenomena which accompanied those mutations. From this review I expect to be able to show that the world’s stock of specie, which is now of great magnitude, consists nearly one-half of silver ; that any diminution or disuse of such stock, whether resulting from failure of the mines or arbitrary legislation, is fraught with the greatest disasters which can befall society ; and that, therefore, the two measures to which our country is committed by existing laws, viz : resumption in specie, combined with demonetization of silver, are likely, if attempted to be enforced, to end in distress and defeat.

Fourth. Therefore one of these measures will have to be abandoned, and that one is the demonetization of silver. In other words, we shall have to restore the double standard of gold and silver which existed from 1792 to 1873.

Fifth. I next review the relative value of gold and silver from the earliest times to the present, and show how constant that relation has been, particularly since the discovery of America and the opening of the East India and China trades, since which time and up to 1873 it scarcely varied from its pivotal point of 15½ to 1. The sources of this long-continued constancy of relation are then examined, and in their nature is found strong assurance that the relation will continue to be constant in the future.

Sixth. The principal and almost only cause of aberration in this relation is found to be the various edicts or enactments which in various countries and at various times have interfered with the freedom of money. Prominent among these were the demonetization of silver in England in 1816, the monetary treaty of the live powers in 1865, the demonetization act of the United States in 1873, and the pending measures of the German government. These various measures are adverted to and condemned as mischievous interferences with trade.

Seventh. The impracticability of abolishing the double standard is greatly strengthened by reference to the annual supplies of gold and silver separately since the beginning of the present century. From this reference it appears that the supplies of gold to the world have fluctuated between $5,000,000 and $182,000,000 per annum ; that the supply has been diminishing since 1852, and that it is at the present time insufficient to meet the demands of the world for that metal for use in the arts and to keep good the wear and loss of coin. On the other hand, the annual supplies of silver have always been steady, and are now but little above the average. Moreover, gold is shown to be essentially a British product, while silver is essentially American.

Eighth. I then propose to show the impossibility of resuming specie payments in gold, the disadvantages and danger of attempting to demonetize silver, the impracticability of demonetizing it permanently, and to discuss the various objections that have been urged against remonetization.

Ninth. I shall also endeavor to show that the effect of remonetizing silver, or rehabilitating the double standard, will be to equalize more nearly the values of the metals, so as to restore or tend to restore the relation that has hitherto, up to within a late date, existed between them for three centuries, and to afford a great impetus to the industrial and commercial prosperity of this country.

Tenth. I shall next endeavor to show that both gold and silver together at a relation fixed by law is the constitutional money of this country, and that all acts of legislation intended to subvert this institution are illegal and void.

Eleventh, and finally. I will quote the authority of the most eminent legislators and publicists in favor of the double standard.