Silver as Legal Tender.

The Presiding Officer. The Chair now lays before the Senate the special order, which is the bill (H.R. No. 3398) for the issue of coin, and for other purposes, on which the Senator from Missouri [Mr. Bogy] is entitled to the floor.

The Senate, as in Committee of the Whole, proceeded to consider the bill (H.R. No. 3398) for the issue of coin, and for other purposes, the pending question being on the amendment reported by the Committee on Finance, which was to strike out all after the enacting clause of the bill, and in lieu thereof to insert:

That there shall be coined at the mints of tho United States a silver dollar of the weight of 412.8 grains troy of standard silver, the emblems, devices, and inscriptions of which shall conform to those prescribed by law for the golg and silver coins of the United States, with such modifications thereof as may be necessary to render the said dollar readily distinguishable from the trade-dollar; and in the coinage and delivery thereof the same deviations from standard weight and fineness shall be allowed as are prescribed by law for the trade-dollar; and the said dollar herein authorized shall be a legal tender at its nominal value for any amount not exceeding $20 in any one payment, except for customs duties and interest on the public debt, and shall be receivable in payment of all dues to the United States except duties on imports.

Sec. 2. That the Secretary of the Treasury is hereby authorized to exchange the silver dollars herein authorized, and also the subsidiary coins of the United States, for an equal amount of United States notes, which shall be retired and canceled and not be again replaced by other notes. And all United States notes redeemed under this act shall be held to be a part of the sinking fund provided for by existing law, the interest to be computed thereon as in the case of bonds redeemed under the acts relating to the sinking fund.

Sec. 3. That the silver bullion required for this purpose shall be purchased from time to time at market rate by the Secretary of the Treasury with any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated; but no purchase of bullion shall be made under this act when the market rate for the same shall be such as will not admit of the coinage and issue as herein provided without loss to the Treasury; and any gain or seigniorage arising from this coinage shall be accounted for and paid into the Treasury, as provided under existing laws relative to the subsidiary coinage: Provided, That the amount of money at any one time invested in such silver bullion, exclusive of such resulting coin, shall not exceed $1,000,000.

Sec. 4. That the trade dollar shall not hereafter be a legal tender, and the Secretary of the Treasury is hereby authorized to limit, from time to time, the coinage thereof to such an amount as he may deem sufficient to meet the export demand for the same.

Mr. Bogy [Lewis Vital Bogy (April 9, 1813 - September 20, 1877); Saint Louis Missouri, D; studied law, admitted to the bar]. Mr. President, whatever may be the fate of the amendments to the bill of the Senate Finance Committee offered by me, I shall rejoice that this discussion has taken place in this body and from here has gone to the country. The subject is one of the most interesting in the whole range of political science, and is as important as it is interesting. It cannot be denied that, for some reason difficult to be explained at this day, the true position of silver as one of the coins of the Constitution had been entirely overlooked, and indeed I may say that it was forgotten by the public mind of the nation. The fact that it could be made useful even as a subsidiary coin was also forgotten, and the greater fact that it could be made a legal tender, as now proposed, was in a manner not known. This discussion has brought these important facts to the knowledge of the people, and a spirit of inquiry has thereby been created. Why the act of 1873, which forbids the coinage of the silver dollar, was passed no one at this day can give a good reason.

As we see this question at this time no possible harm could have resulted in permitting silver to occupy the position it had held before. The amount coined from 1870 to 1873 was $3,336,348. This could have done harm to nobody. Therefore the quantity of silver then on hand or being coined was not large enough to justify the legislation of that day. We must look for the reason for this legislation elsewhere. We will find this to be part of the idea, starting in England in 1816, and which has spread to the countries of Europe and also to this Country: that gold was the only true standard, and silver, after a glorious reign of thousands of years, beginning in the very twilight of civilization and continuing down the ages to the period of its meridian splendor, had to be dethroned. The visionary theorists of England, these men of new ideas as to the origin of man as well as his final destiny, have by noise and clap-trap inoculated the one-idea men of the continent, and therefore one standard has at this day many advocates over all Europe, and, strange as it may appear, the practical mind of this country was for a time, and until this discussion took place, under the complete sway of this class of men.

The practical mind of the Senator from Vermont [Mr. Morrill] is yet uncler this influence. I am happy to say, judging from his last speech, that the Senator from Ohio [Mr. Sherman] is fast abandoning this school of theorists. I regret I cannot say as much for the Senator from California, [Mr. Booth.] Judging from the speech he made on this subject I think that he belongs to this class of theorists.

My object on this occasion will be to place before the country the necessity for us to return as soon as possible to what is generally known as the double standard; that is, a standard composed of the coins of gold and silver.

The Senator from Ohio in his last speech has admitted many of the positions assumed by me in my former speech --that is, that our obligations, in the shape of bonds and otherwise, issued before the act of 1873, being payable in coin, could legally be paid in silver, as this metal was a recognized coin up to that time; and so with the duties on imports. He now admits that these could be paid in silver. That is all I advanced at the time I made my speech, and for which I was held up before the country as a sort of repudiationist, having no regard for the public credit.

At the time I proposed an amendment to the committee's bill that duties should be payable in silver equally as in gold, I was well aware that we had no silver in the country; that, it having been unwisely demonetized some years before, none had lately been coined, and consequently there was none here. My object was to have silver recognized; and, as I understand the Senator from Ohio who is chairman of the Committee on Finance, this fact is now admitted. I have accomplished one of the objects I had in view at the outset of this discussion, which was to have silver recognized as one of the constitutional metals, and with which we could pay our obligations, and that it was also receivable in payment of duties. It is said by the Senator from Vermont, and others who oppose my amendment, that to pay the interest on our public debt or our bonds in silver would be an act of bad faith. It is virtually admitted by this Senator that according to strict law this could be done, as the bonds and coupons are payable in coin, and at the time they were made silver was a legal coin, but that outside of the letter of the law it was understood that gold alone was contemplated. If silver can be made as valuable as gold --that is, if a silver dollar of a given weight can be made as good as a gold dollar of a given but lesser weight-- where would the bad faith be ?

The answer to this question presents the only solution of the problem. If it be true that silver can be made to be as valuable as gold, then there would be no bad faith, for the creditor would receive as much in one way as the other. The arguments of both the Senators from Vermont and California in opposition to making silver a legal tender are based on the fact that silver is of much less value than gold, and is subject to great variations in value. While it is true that silver is intrinsically of less value than gold, and has been so in all ages, nevertheless until recently it was used by all nations with perfect success, by establishing a certain ratio or relative value between the two metals.

The relative value of silver to gold in the days of the patriarch Abraham was ....... 8 to 1

One thousand years before Christ .................. 12 to 1

Five hundred years before Christ .................. 18 to 1

At the commencement of the Christian era ..................... 9 to 1

A.D. 500 .................................... 18 to 1

1100 ................................ 8 to 1

1500 .............................. 11 to 1

1500 ............................. 2 to 1

1600 .............................. 11 to 1

1613 ............................... 13 to 1

1700 ......................... 15½ to 1

1816 .......................... 14 to 1

1847 .......................... 15½ to 1

It will be observed from this table that the relative value has been pretty uniform, and it is now the same that it was in the year 1700, which is one hundred and seventy-six years ago. Thus for this long period of time this relation has not changed, and it will be observed that this was during the period when the condition of the social and political world, as well as the commercial world, was changing from the bottom to the top. This period also witnessed the greatest difference in the production of the two metals. Yet during all these disturbing causes this relation has remained stationary.

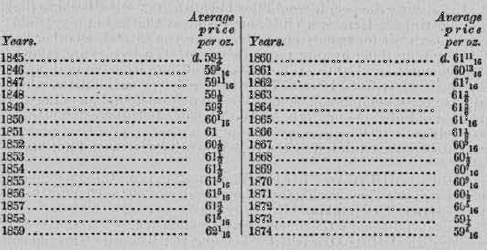

Up to near the close of 1874 the price had been remarkably steady, as may be seen from the following statement taken from the annual circular of Pixley & Abell, London. The prices are for standard bar silver, and are the average annual price for each year named:

From the latter part of 1874 the price has continued to decline, until now the quotation is about 53½d., against about 60d. during the thirty years given above. The truth is, that in 1837 we placed too high a value on silver compared with gold; that is, we made the difference 16 to 1, and, as a consequence, our silver dollars were more valuable than gold, and passed out of the country or out of existence rapidly. Hence since 1853 we have coined no silver dollars under this old law, although the authority to do so has remained in force until the act of 1873, when it was taken away by the following provision: "That no coins, either of gold, silver, or minor coinage, shall hereafter be issued from the Mint other than those of the denominations, standards, and weights herein set forth." But even after 1873, and until the Revised Statutes of 1874, the old silver dollar remained a legal tender to any amount.

From this table, taken from an authentic publication issued in London, it will be seen how steady and regular has been the value of this metal until very recently. The cause of this depression is easily understood, and it is only surprising that it has not been greater. This metal is now demonetized in England, Germany, and the United States, besides several other countries. The demand for it, therefore, for coinage is very limited; not only is this so, but the large amount of old coin in the different German kingdoms and principalities, amounting to the large sum of three hundred and fifty millions, was thrown on the market to be exchanged for gold. France and the other Latin nations were compelled, as a measure of protection against this foreign silver invasion, which would have drained them of their gold, to pass laws limiting the amount of silver coinage.

The Senator from Ohio stated in his last speech that this limit to silver coinage in France and other southern countries was owing to the fact that silver was gradually becoming less valuable than gold, hence the necessity of limiting the quantity. This is not the fact. This limit was made necessary to prevent the German silver from flooding the country and taking away the gold in its place. Indeed, all these laws limiting the amount of silver annually coined is owing to the fact that England and Germany and other countries using nothing but gold would in time absorb all the gold from the other countries, and these would retain nothing but the silver. It is a measure of protection as against foreign countries. But if all these countries now having but one standard had the two, these protecting measures would not be necessary.

If silver was made a legal tender in this country for all amounts and for everything, including the payment of the public debt and duties on imports, there can be no doubt that it would at once be as valuable as gold, provided the relative value between the two was correctly fixed by law. In Europe this is 15½ to 1, and my first amendment fixed it at this rate. I did so at the time not with the view of adhering to it, but because this was the relation in Europe, and my object was to discuss the question on the European basis. This was evident from the fact that I had not propose to change the weight of the silver dollar. I believe that the relation should remain at what it was when we had the double standard; that is, 16 for 1. The silver dollar proposed to be coined is 412.8 grains troy. The gold dollar is 25.8 grains. Now, sixteen times 25.8 is 412.8. By adhering to this relation no change is made.

Much has been said about the faith of the nation and the national honor. The Senator from California gave wings to his imagination when speaking of this. This would be all very well if any one here or elsewhere proposed to do anything to tarnish it or to place on it a speck the size of the dot of a pin. I am for maintaining the national honor, and am ready to make as many sacrifices to do this as any man. This is not done by mere declamation. Tropes and figures of speech or hyperboles are not coinable. In war this honor is maintained on the field of battle, and in peace by a strict compliance with all engagements, public and private, for they go together; for the individual who has no private honesty cares not for the public faith, however much he may prate about it.

To pay in silver is said to be bad faith. And why ? Because it is said not to be of equal value to gold. But if made of equal value to gold will it not answer the same purpose ? If a silver dollar can be made as good as a gold dollar, certainly the home bondholder would lose nothing by taking silver; and as to the foreign bondholder, the facts are entirely different. No one, I presume, is so ignorant as to believe that we send gold in kegs to Europe to pay our semi-annual interest. This is effected by buying of exchange on London, Paris, or Berlin, as may be required. If silver is as good as gold in this country, this exchange would cost no more if paid for with silver in the place of gold. Yet the Senator from Vermont dwelt at length on the fact, that as soon as the European bondholders were informed that we were paying our bonds in silver, these bonds would at once be sent home to be paid. The Senator could not have thought much before he wrote this part of his speech. According to him, these foreign bondholders would be in a hurry to send their bonds forward to be paid in silver; or does he mean to say that these bonds would be sent here to be sold at any price for gold ? Such arguments are not well founded. The foreign bondholder would receive his interest the same as he does now.

The question arises, then, why introduce silver to pay this character of debt if no one is benefited or hurt by it. In this aspect the subject assumes proportions that are world wide. As silver and gold have been the precious or royal metals used by all nations, civilized, semi-civilized, and barbarian, in all ages, all the world over, those who advocate it being used yet for this purpose cannot see any good reason why it should be discarded. Owing to the introduction of steam for ocean navigation, and the use of the wondrous improvement of modern times, the telegraph, now circling the earth, commerce, previously somewhat restricted as to space and limited as to amount, is now co-extensive with the globe, and the amount so vast as to be nearly beyond the limits of computation.

There is at this day no sea, broad or narrow, bay or inlet, no valley or mountain, point of land or elevated peak, on the Earth's surface but is now visited by the agents of commerce. Hence, as commerce has extended over a larger space and has increased in amount to an extent which may be called enormous, it does not seem wise to curtail the means of exchange by one-half. The effect of this attempt has by necessity brought about the use of paper as money, and this necessity has given rise to different schools of paper philosophers or paper financiers. At the outset, the paper men believed in a convertible paper at all times and everywhere; but now, as coin is less by one-half than formerly, and consequently hard to procure, these paper promises are never to be converted, but to be exchanged as the fancy of the party might dictate --a short promise for a long one-- that is, a greenback, which is a promise to pay on demand, but which promise is never to be redeemed, for a bond of 3.65, payable years after date, with the understanding that when these years roll round it is not to be paid, but is to be taken up with another bond. This is called a financial system founded on the public credit or the faith of the nation, and is advocated by the Senator from California [Mr. Sargent]; yet that Senator spoke at length and eloquently about national honor.

How long would the honor of the nation last under such a system ? To avoid the necessity of the use of irredeemable paper as money we desire to restore to its place the old silver metal. There being about as much silver as gold in the world, to demonetize silver one-half of the circulation of the world is destroyed, and this at a time when the needs of commerce require a larger amount. The effect has been to centralize wealth, first in a few favored nations that are creditors of the balance of the world, and then in the hands of few individuals in each of these nations. The capitalist and the receiver of fixed rent, the bondholder, and all men of fortune are made richer by it, as the purchasing power of a dollar is doubled by destroying the one-half of the money of the world; whereas the laborer, and indeed all persons who depend on their daily labor for a living, are reduced, for the same reason, to one-half of what they received before.

The result is plain and is now before our eyes in our own country as well as abroad. There are at this day as many really poor people as as ever before --indeed I may say many more-- while individuals in this country and in Europe are very numerous who count their private fortunes by many millions. We have some men in this country who are worth to-day one hundred millions. In addition to this, these men of large fortunes pay no portion of the public debt in the way of taxes, the bonds they own, and for which they want gold, paying no taxes.

There are two sides to this question of national honor. The man who receives his regular interest on his bond represents only one class; there is another class, who has no bonds, and pays a portion of taxes. It is for the interest of this last class that silver should be made a legal tender, because by increasing the circulating medium of this country and of the world you increase its means of payment, and at last it is this class on which your bondholders, capitalists, and wealthy men depend; they are like the foundation of the house, supporting the whole edifice; destroy them, and you destroy the foundation, and the whole falls to the ground.

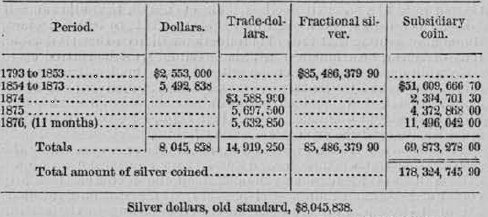

The Senator from Vermont appended to his speech a table showing the amount of silver dollars coined since 1792. While this table is correct, it is only so to a very partial extent. It gives only the amount coined in dollars, but not the total amount of silver turned out of the Mint. From 1792-'93 to 1853, $85,486,379.90 in fractional silver currency was turned out by the Mint of Philadelphia. From 1792 to the present time $178,324,745.90 of silver money has been turned out by the mints of this country, as per the following table, furnished by Dr. Linderman, the Director of the Mint:

The Senator from California [Mr. Sargent] said that the coinage capacity of all our mints was fifteen millions a year. The Director of the Mint informs me that this capacity is equal to thirty millions a year. In eleven months of this year, as per the table above, upward of seventeen millions has been coined, two-thirds of this being in small coins.

The national honor, the public faith, the necessity of restoring prosperity to the country, the further necessity of giving stability to our financial system, all point to one direction --the increase of the metallic basis in the place of the purely artificial system, now resting alone on promises to pay, and which are never redeemed, and founded alone on what the Senator from California calls the public credit. In this respect the national credit does not differ from the credit of a private person, who, however honorable be may be, however upright, however honest, if he issues his promises to pay and does not redeem them, or does so by issuing a new promise, his credit will go down in spite of his honor.

The coin basis can be increased only by the use of silver, of which we are now producing some forty millions annually, with the good promise that when our silver-producing fields in Colorado, Montana, Arizona, and New Mexico, in addition to those already known in Utah and Nevada, are sufficiently developed, the quantity produced may be quadrupled. While this is so as to silver, the reverse is known to be fact as to gold, as the annual production is now diminishing, and without any prospect for an increase. The total product of silver from Nevada from 1861 to 1875 is $215,000.000. This country now furnishes one-half of the silver and one-fourth of the gold produced in the world. The annual product of silver has doubled within a quarter of a century.

A London journal makes the following computation of the annual production of gold and silver, stated in pounds sterling, in the quinquennial periods terminating with and including the years named:

Year. Gold. Silver.

1856 ... £29,900,000 .... £8,100,000

1861 ..... 24,500,000 ...... 8,200,000

1866 ..... 22,700.000 ...... 9,900,000

1871 ..... 23,000,000 ...... 10,500,000

1875 ..... 20,400.000 ...... 13,900,000

These computations correspond with those ordinarily made. Exact accuracy is not to be expected in statements of this sort. As given, the table shows a relative advance in the silver production since 1851, which is undoubtedly considerable. In the first five years the silver production was only a little more than one-fourth that of gold. In the last period this proportion had risen to two-thirds.

Now let us see how this compares with the relative gain in the gold production which resulted from the California and Australia discoveries. In a very meritorious work, entitled "Money," published in 1863 by Charles Moran, it is computed that the gold produced in the world prior to the new discoveries was to silver as 1 to 46 in weight, which would be the same thing as 1 to 3 in value, but had become in 1853 as 1 to 4 in weight, which would be the same thing as 4 to 1 in value. This is probably correct as to 1853, and it is probably so as to the times preceding the California discoveries, except after the discovery of the Siberian mines in Russia in the reign of the Emperor Nicholas. But even after that no estimate of gold production makes it equal to that of silver before the days of California. M. Chevalier (Fall in Gold, 1857) reckons the then annual production of silver (in pounds sterling) at 8,850,000, and states that it had not much varied since the commencement of this century, when it stood at 7,965,000. As to the annual gold production, he fixes it at the beginning of this century at 2,484,000, and makes the average from 1800 to 1848, which includes a part of the period of gold development in Siberia, at 3,250,000.

On these figures, in the twenty years following the California discovery, as compared with the forty-eight years prior thereto, the gold production was multiplied about seven times, while that of silver scarcely increased at all. On the other hand, the gain in silver during the last ten years, as compared with the preceding twenty years or fifty years, is only about 50 per cent. The silver gain within ten years is, it is true, relatively greater than that, because the production of gold has recently declined; but even with that allowance it falls far behind the relative gain of gold from 1848 to 1858. In fact, if one may assume that the gold production will hereafter not decline, that of silver, now fourteen millions sterling, must be carried up to sixty millions before it will recover the ratio to gold which it maintained for probably a century before the Siberian discoveries. As we shall see, the gain in gold after 1848 did not sensibly affect the equilibrium of the two metals. Why, then, should we believe that the much smaller gain in silver does so now ?

The proposals of the Paris conference of 1867, re-enforced by the practical interests which looked for sinister gains from an appreciation in the value of money, bore fruit in the decree of the newly constituted German Empire of December, 1871, prescribing the steps leading to an exclusive gold standard, and resulting in the casting out from its circulation of $350,000,000 silver. Several adjoining small states have judged themselves unable to resist this example of a great and powerful neighbor. Hence the treaty of Sweden and Denmark of 1873 for an exclusive gold standard to come into operation January 1, 1874. Hence the apparent acquiescence of opinion among the Dutch, who still avow their preference for silver, that they too must soon adopt gold as the only standard. Hence the suspension by Belgium in 1873 of the coinage of silver, and the demand made by Switzerland in the same year for a new conference of the four states (called the Latin union) of Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, and France, bound to the double standard by the treaty of 1865, not expiring by its terms until 1880. Hence the new conference at Paris in January, 1874, as demanded by Switzerland, at which, although the double standard was still maintained, the annual coinage of legal-tender silver was prescribed for each country; an arrangement which, with slight modifications, is still in vogue.

In addition to this legislation of European countries, the fall in silver has been somewhat aided by the apparent concurrence of the United States in 1873 in the single-standard scheme. The fall may have been accelerated and perhaps aggravated by a temporary diminution of the demand for silver from India. In the eleven years from 1853 to 1863, both inclusive, when the combined streams of gold from California and Australia were at their fullest height, $100,000,000 per annum, the average price during each year of an ounce of bar silver in London stood at five shillings one penny and a fraction of a penny in gold. The whole range of the fluctuation was in the magnitude of this fraction of a penny, which never went below one-fourth and never went above seven-eighths. Thus the extreme variation of the gold price of one ounce of silver from 1853 to 1863 was only five-eighths of a penny. Now is it for one moment credible that the fall in the price of the ounce of silver in London to three-fourths of a penny below five shillings in 1873 (the lowest price reached in any one of the forty preceding years) and the still more astounding fall to seven pennies below five shillings in March, 1876, are the results of variations in the relative production of gold and silver, when we know that variations vastly greater in times past have produced no such disturbance of price or any approximation to it ?

It is not any excess of production of silver past, existing, or probably impending which has depreciated it, but it is the movement to deprive it of its ancient function as money, inaugurated at the international conference held at Paris in 1867, a mixed body of diplomats and savants with a large proportion of visionaries, theorists, and impracticables.

When properly viewed, this fact of the low price of silver is a most alarming thing; and if it is not arrested, and that speedily, all the nations of Europe, the Latin nations as well as the others, and the Indies too, will be compelled to resort to gold as the only standard. This will become a necessity as a measure of self-defense, and not because it may be desired by those nations having now the double standard. I said this fact was most alarming; and this is true. Germany was thrown into a perfect state of paralysis by demonetizing silver, and in this country, partly from the same cause, we have but a limited quantity of precious metal. Make the single standard the law throughout the world, you thereby reduce the medium of exchange one-half, and a monetary crisis will consequently be created, not confined to one country or one hemisphere, but to all countries and both hemispheres; and this not for one day, but for a generation or more. Poverty, squalid poverty, will be the lot of the laboring population of the globe, while the already rich will become richer by increasing the purchasing power of the gold dollar. In time this would lead again to the restoration of the double standard. All nations would be compelled to restore it as the only way and the only means to maintain social order and preserve the autonomy of the different states now composing the family of nations. The laboring-man, he who earns his living by the sweat of his brow day by day, has an interest in this question which true wisdom should teach us not to overlook.

A joint resolution has been introduced by the Senator from Ohio [Mr. Sherman] pledging our readiness at any time to join in a conference of the European powers on the subject of the relation of gold and silver and of the double standard. While I would prefer that we should at once invite these parties to join us at an early day, I am willing to give my support to the resolution already introduced. I hope this convention will assemble soon, otherwise France and Belgium, from necessity produced by outside pressure, will be compelled, as the only measure of self-protection against the silver invasion from England and Germany, to adopt the single standard. Neither one of these powers is disposed to this as a matter of choice, but I repeat the necessity may be forced on them. While this may not include either Italy or Austria, nevertheless it will be equivalent to making gold the only standard in the commercial world.

Although, as I have already said, all the commercial nations would in time be compelled to abandon this and return to the double standard, for the simple reason that there is not gold enough to supply the demand for it, if it be the only standard; nevertheless this point of a return to the double standard would not be reached before a long and bitter trial of the single standard, which would be the most dreadful and terrible ordeal which at present and in the now condition of the world could afflict the human race. We know how scarce the precious metals were during the Middle Ages, and for this reason how perfectly dependent on the wealthy land-owners and great barons, who then held sway, were the masses of the people. But the condition of this class is now different, and would, if reduced again to dependence, be infinitely worse now than at that time. Then he had a protector in his liege lord, and was willing to submit because his condition had been one of submission for generations, as was the case in Rome, where the equestrian order had its clients and dependents. But now, with the air of liberty surrounding him, his manly spirit will not brook dependence upon any lord or protector; he claims to be able to protect himself; and the consequence would be that a spirit of resistance would be created and let loose throughout the world, brought about by this forced condition of poverty, not only inimical to social order, but utterly destructive of everything like free government. Make this class of men pariahs, and they will make themselves pirates; war on them, and they will in self-defense war on you. The attempt to subdue them would lead to rebellion and revolution and consequent subversion of free government, and social and political chaos would be the necessary result. Leaders would spring up with genius and ability and selfish ambition, and, wielding this great power of the masses, the wealthy class and free governments would be destroyed; and for ages again the world would be thrown back to the condition it was in ages past, and man again would be plunged into slavery.

This subject, which has for some years been overlooked, engaged the attention of the statesmen of this country as early as 1828. On the 29th of December, 1828, a resolution was adopted by the Senate "requiring the Secretary of the Treasury to ascertain, with as much accuracy as possible, the proportional values of gold and silver in relation to each other." On the 4th of May, 1830, S.D. Ingham, then Secretary, submitted to Congress his report in answer to this resolution; it is Document No. 117, first session Twenty-first Congress. It is truly able and exhaustive, and worthy the study of any one investigating this subject. Appended to this report I find two papers, one from Mr. Gallatin and the other from Alexander Baring, a member of the British Parliament, and ranked among the most eminent and practical financiers of his day in England. I will here give extracts from the papers of these two distinguished men:

Albert Gallatin in Favor of the Double Standard.

On the 31st of December, 1829, at the request of the Treasury Department, Albert Gallatin submitted his views upon the relative value of the two precious metals, and upon various coinages, concluding with a defense of the double standard of this country, and in opposition to the British system of a single gold standard. Gallatin, during the first epoch of our national history, had no rival as a financial authority except Alexander Hamilton, the suffrages of the country being divided between them by party preferences, but the eminence of both being acknowledged by all. On the question of the double standard, fixed by the Constitution, they were in perfect harmony. Hamilton's views were given in his report of 1792 on the Mint. If those of Gallatin will weigh more at this day, it is because they were given after the British system had been introduced in 1816, and had been tried in practice. In 1829 he had retired, full of honors, from public life, and had become the head and pride of the bankers of our commercial metropolis, and this is what he then said:

"Great Britain, till the year 1797, when the suspension of cash payments took place, and all other nations to this day, have used the two metals simultaneously without any practical injury, and to the great advantage of the communities, though in many instances sufficient care had not been taken to assimilate the legal to the average market value of the two metals. A fact so notorious, so universal and so constant is sufficient to prove that the objection, though the abstract reasoning on which it is founded is correct, can have no weight in practice.

"The whole amount of inconvenience arising from the simultaneous use of the two metals consists in this: Their relative value being fixed by law, if this changes in the market the debtor will pay, in the cheapest of the two metals, at a rate less than the standard agreed on at the time of making the contract."

Upon this Mr. Gallatin observes that it will not be true that the debtor pays less than was agreed, unless "the change in the market price is due to a fall in that of the metal in which he pays his debts." and that "if the change is due to the rise" of the other metal, he pays all that was agreed. But, answering further, he say:

"But the true answer is that the fluctuations in the relative value of the gold and silver coins, arising from the demand exceeding or falling short of the supply of either, are less in amount than the fluctuations, either in the value of the precious metals as compared with that of all other commodities, or in the relative value of bullion to coin, and even than the differences between coins, particularly gold coins, issued from the same mint; and therefore that those fluctuations in the relative value of the two species of coins are a quantity which may be neglected, and is, in fact, never taken into consideration at the time of making the contract.

"The simultaneous rise and fall of the true metals, in relation to all other commodities, though not susceptible of being precisely valued, does often take place to a greater amount than any of the other fluctuations. It is evident that whenever such rise does take place, whether generally or on the spot, it is an advantage to be able to resort to both the metals, and that if the rise is only on one of the metals, for which there happens to be a greater demand, and that should be the sole legal tender, it will be exported, and diminish in a most inconvenient way the whole amount of specie; a diminution which, in that case, cannot be remedied by resorting to the other metal which is not a legal tender. That inconvenience is still greater when gold is the metal selected for currency to the exclusion of silver, the annual supply of this last metal being much larger in value than that of gold."

Commenting upon the English policy of demonetizing silver, Mr. Gallatin says:

"But not only has England by that experiment, in the face of the universal experience of mankind, gratuitously subjected herself to actual inconvenience for the sake of adhering to an abstract principle, but in so doing she has departed more widely from known principles and from those which regulate a sound metallic currency. While pretending to exclude silver, she admits it, and makes it a legal tender for all that multitude of daily purchases and contracts under forty shillings at an overrated price.

"Even if the precedent were good, it could not be conveniently adopted in the United States. To the exclusion of silver there are great objections. The American dollar of 371¼ grains of pure silver is the unit of money and standard of value on which all public and private contracts are founded."

What would have been the amazement of Albert Gallatin if he had lived until 1873, when public, corporate, and individual debts had attained a magnitude never dreamed of in his day, the national debt two thousand millions, State and municipal debts as much more, and other debts perhaps ten times as much, but all founded on "the American dollar, or 371¼ grains of pure silver." as "the standard of value," and all payable in that standard; to have witnessed the spectacle of a Congress of the United States, enacting in carelessness that all debtors, including the nation, should be deprived of their plain and essential rights and condemned to pay in the single metal of gold, certain to be carried by the universal scramble for it to an unheard-of price as measured in all property, real and personal !

Extracts from minutes of evidence taken from the committee for coinage at the board of trade April 26, 1828.

Alexander Baring, esq., M.P., examined:

Question. Is it your impression that it is possible and desirable to maintain in this country a silver currency as a legal tender founded on the proportion of silver to gold established in the currency of France, or something very near it, at the same time that we maintain our present silver currency, which is obviously not in that proportion, and that there would be an advantage in that system ?

Answer. I have always thought so, and certainly think so still. I have no doubt about it.

Q. The circulation of the country would then consist of a silver coinage, of tokens being a legal tender only to a limited amount, and a silver coinage being a legal tender to an unlimited amount, and a gold coinage ?

A. Exactly so.

Q. What are the advantages which you contemplate from the addition to our present currency of a silver currency consistent with the token silver issued in the manner you have described ?

A. The value of a medium of circulation in a country where it is necessarily combined with much paper, and especially when the paper forms the larger portion, depends on its flexibility, on its power of contraction and expansion to meet the varying circumstances of the times. * * * A sudden change from peace to war, a bad harvest or a panic year, arising from overtrading and other causes, immediately imposes upon the Bank of England, which is the heart of all our circulation, for tho purpose of protecting itself, to stop the egress of specie; sometimes even to bring large quantities into the country. These indispensable remedies are always applied with more or less of restriction of the currency and consequent distress. * * * No care or prudence can enable the great bank to avoid occasional resort to those measures of defense; and that system of currency is the best which admits of their being made the least frequently, and with the least effort and derangement. Now, it is evident that the bank, wishing to re-enforce the supply of specie, can do so with infinitely increased facility, with the power of drawing gold or silver, than if it were confined to one of the metals. * * * That medium of legal tender is best which affords the best security against these forced operations. The greater the facility of the bank to right itself in these constantly recurring ebbs and floods in its specie, the greater will be the facilities of those who depend upon it, and the less frequent will be those sudden jerks and changes so fatal to credit and commerce. * * * That the efforts of the bank in 1825 for self-preservation made great havoc among its dependents throughout the country is well known: and I believe it is equally so that, while it was rummaging every corner for gold, which could alone answer its purpose, it was sending large sums of silver from its coffers, which were perfectly useless.

To the question whether it was possible to fix a legal ratio of the two metals to which the market ratio would always correspond, he replied that it was not. He said that the market ratio "will vary with the variations in the relative value of the metals, however wisely you may adjust the difference," and that, as a consequence, under the double standard, "the practical currency may change from one to the other." But there was nothing in this which seemed to alarm him or shake his conviction that the double standard was the best. He said:

"In these matters practical experience is worth all the theories of mere speculation. The variation in France is seldom above 1-10 per cent.; it sometimes runs up to a quarter per cent. It has been, I am told, something higher on particular occasions. When the Bank of England was running all over the continent for gold, this was the case."

The country is at this moment in a terrible crisis. We hear every day of new failures. The largest manufacturing establishments, the heaviest mercantile firms, the most enterprising men --those men who have done the most to employ labor and to create wealth-- are going down before this terrific storm. Those large establishments and heavy firms are like the tall trees of the forest, around whose heads the lightnings have played for a century and whose majestic branches and thick foliage have given shade and shelter to the animals of the woods for many long years; but their great height also invites the lightning's stroke and their thick foliage and wide-spreading branches expose them to the winds and storms that sweep around the earth. These tall trees go down, torn by the roots, when the small and delicate shrub remains unharmed.

Mr. President, some time ago I offered three amendments to the Senate bill. I will take them in the inverse order. The first one was fixing the rate or ratio between silver and gold at 15½ to 1. As I stated in my speech, this was not correct, and I knew it was not at the time. It is not necessary to fix any rate at all, because the rate fixes itself. The relation of 16 to 1 would remain, because the silver dollar is 412.8 grains, the gold dollar being 25.8, and 25.8 multiplied by 16 makes 412.8. That amendment I desire to withdraw. Another amendment which I desire to withdraw is that which provided that duties on imports might be paid with silver, and also the interest upon the public debt. I will not detain the Senate by giving the reason at this late hour; but I am willing to concede that it would be better for the time being that the duties and the interest should be paid with gold. Indeed, I may say briefly that it is better for us at this time that silver should not be too valuable. I believe that we have a right to pay in silver, but silver will be very scarce for at least one year to come, and we shall have ample time. It will be much more desirable that silver may not be too valuable. If you make it too valuable you at once make a merchandise of it, and it will cease to be in circulation. I will confine all my amendments to one point, to strike out the words "not exceeding $20," so that silver shall be a legal tender for all sums, except for duties on imports and interest on the public debt.