Public Acts of the Thirty-Seventh Congress

OF THE

UNITED STATES

Passed at the first session which was begun and held at the City of Washington, in the District of Columbia, on Thursday, the fourth day of July, A.D. 1861, and ended on Tuesday, the sixth day of August, A.D. 1861.

Abraham Lincoln, President.

Hannibal Hamlin, Vice-President, and President of the Senate.

Solomon Foote was elected President of the Senate, pro tempore, on the eighteenth day of July, and continued so to act until the close of the session.

Galusha A. Grow, Speaker of the House of Representatives.

—An Act to authorize a National Loan and for other Purposes.

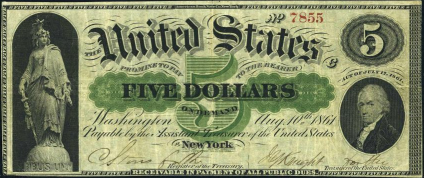

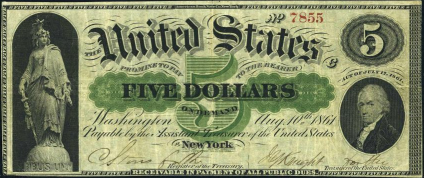

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Secretary of the Treasury be, and he is hereby authorized to borrow on the credit of the United States, within twelve months from the passage of this act, a sum not exceeding two hundred and fifty millions of dollars, or so much thereof as he may deem necessary for the public service, for which he is authorized to issue coupon bonds, or registered bonds, or treasury notes, in such proportions of each as he may deem advisable; the bonds to bear interest not exceeding seven per centum per annum, payable semi-annually, irredeemable for twenty years, and after that period redeemable at the pleasure of the United States; and the treasury notes to be of any denomination fixed by the Secretary of the Treasury, not less than fifty dollars, and to be payable three years after date, with interest at the rate of seven and three tenths per centum per annum, payable semi-annually. And the Secretary of the Treasury may also issue in exchange for coin, and as part of the above loan, or may pay for salaries or other dues from the United States, treasury notes of a less denomination than fifty dollars, not bearing interest, but payable an demand by the Assistant Treasurers of the United States at Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, or treasury notes bearing interest at the rate of three and sixty-five hundredths per centum, payable in one year from date, and exchangeable at any time for treasury notes for fifty dollars, and upwards, issuable under the authority of this act, and bearing interest as specified above: Provided, That no exchange of such notes in any less amount than one hundred dollars shall be made at any one time: And provided further, That no treasury notes shall be issued of a less denomination than ten dollars, and that the whole amount of treasury notes, not bearing interest, issued under the authority of this act, shall not exceed fifty millions of dollars.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That the treasury notes, and bonds issued under the provisions of this act shall be signed by the First or Second Comptroller, or the Register of the Treasury, and countersigned by such other officer or officers of the Treasury as the Secretary of the Treasury may designate; and all such obligations, of the denomination of fifty dollars and upwards, shall be issued under the seal of the Treasury Department. The registered bonds shall be transferable on the books of the Treasury on the delivery of the certificate, and the coupon bonds and a treasury notes shall be transferable by delivery. The interest coupons may be signed by such person or persons, or executed in such manner, as may be designated by the Secretary of the Treasury, who shall fix the compensation for the same.

SEC. 3. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Treasury shall cause books to be opened for subscription to the treasury notes for fifty dollars and upwards at such places as he may designate in the United States and under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe, to be superintended by the Assistant Treasurers of the United States at their respective localities, and at other places, by such depositaries, postmasters, and other persons as he may designate, notice thereof being given in at least two daily papers of this city, and in one or more public newspapers published in the several places where subscription books may be opened; and subscriptions for such notes may be received from all persons who may desire to subscribe, any law to the contrary notwithstanding; and if a larger amount shall be subscribed in the aggregate than is required at one time, the Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to receive the same, should he deem it advantageous to the public interest; and if not, he shall accept the amount required by giving the preference to the smaller subscriptions; and the Secretary of the Treasury shall fix the compensations of the public officers or others designated for receiving said subscriptions: Provided, That for performing this or any other duty in connection with this act, no compensation for services rendered shall be allowed or paid to any public officer whose salary is established by law; and the Secretary of the Treasury may also make such other rules and regulations as he may deem expedient touching the instalment to be paid on any subscription at the time of subscribing, and further payments by instalments or otherwise, and penalties for non-payment of any instalment, and also concerning the receipt, deposit, and safe-keeping of money received from such subscriptions, until the same can be placed in the possession of the official depositaries of the Treasury, any law or laws to the contrary notwithstanding: And the Secretary of the Treasury is also authorized, if he shall deem it expedient, before opening books of subscription as above provided, to exchange for coin or pay for public dues or for treasury notes of the issue of twenty-third of December, eighteen hundred and fifty-seven, and falling due on the thirtieth of June, eighteen hundred and sixty-one, or for treasury notes issued and taken in exchange for such notes, any amount of said treasury notes for fifty dollars or upwards not exceeding one hundred millions of dollars.

SEC. 4. And be it further enacted, That, before awarding any portion of the loan in bonds authorized by this act, the Secretary of the Treasury, if he deem it advisable to issue proposals for the same in the United States, shall give not less than fifteen days' public notice in two or more of the public newspapers in the city of Washington, and in such other plates of the United States as he may deem advisable, designating the amount of such loan, the place and the time up to which sealed proposals will be received for the same, the periods for the payment, and the amount of each instalment in which it is to be paid, and the penalty for the non-payment of any such instalments, and when and where such proposals shall be opened in the presence of such persons as may choose to attend; and the Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to accept the most favorable proposals offered by responsible bidders: Provided, That no offer shall be accepted at less than par.

SEC. 5. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Treasury may, if he deem it advisable, negotiate any portion of said loan, not exceeding one hundred millions of dollars, in any foreign country and payable at any designated place either in the United States or in Europe, and may issue registered or coupon bonds for the amount thus negotiated agreeably to the provisions of this act, bearing interest payable semi-annually, either in the United States or at any designated place in Europe; and he is further authorized to appoint such agent or agents as he may deem necessary for negotiating such loan under his instructions, and for paying the interest on the same, and to fix the compensation of such agent or agents, and shall prescribe to them all the rules, regulations, and modes under which such loan shall be negotiated, and shall have power to fix the rate of exchange at which the principal shall be received from the contractors for the loan, and the exchange for the payment of the principal and interest in Europe shall be at the same rate.

SEC. 6. And be it further enacted, That whenever any treasury notes of a denomination less than fifty dollars, authorized to be issued by this act, shall have been redeemed, the Secretary of the Treasury may re-issue the same, or may cancel them and issue new notes to an equal amount: Provided, That the aggregate amount of bonds and treasury notes issued under the foregoing provisions of this act shall never exceed the full amount authorized by the first section of this act; and the power to issue, or re-issue such notes shall cease and determine after the thirty-first of December, eighteen hundred and sixty-two.

SEC. 7. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Treasury is hereby authorized, whenever he shall deem it expedient, to issue in exchange for coin, or in payment for public dues, treasury notes of any of the denominations hereinbefore specified, bearing interest not exceeding six per centum per annum, and payable at any time not exceeding twelve months from date, provided that the amount of notes so issued, or paid, shall at no time exceed twenty millions of dollars.

SEC. 8. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Treasury shall report to Congress, immediately after the commencement of the next session, the amount he has borrowed under the provisions of this act, of whom, and on what terms, with an abstract of all the proposals, designating those that have been accepted and those that have been rejected, and the amount of bonds or treasury notes that have been issued for the same.

SEC. 9. And be it further enacted, That the faith of the United States is hereby solemnly pledged for the payment of the interest and redemption of the principal of the loan authorized by this act.

SEC. 10. And be it further enacted, That all the provisions of the act entitled "An act to authorize the issue of treasury notes," approved the twenty-third day of December, eighteen hundred and fifty-seven, so far as the same can or may be applied to the provisions of this act, and not inconsistent therewith, are hereby revived or re-enacted.

SEC. 11. And be it further enacted, That, to defray all the expenses that may attend the execution of this act, the sum of two hundred thousand dollars, or so much thereof as may be necessary, be, and the same is hereby, appropriated, to be paid out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated.

Approved, July 17, 1861.

THIRTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS.

Session I.

July 4th - August 6th, 1861.

In the House Representatives

Wednesday, July 10, 1861.

NATIONAL LOAN.

Mr. STEVENS. Has the morning hour expired ?

The SPEAKER. It has.

Mr. STEVENS. [Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792 - August 11, 1868), Pennsylvania (R)] I move, then, that the rules be suspended, and that the House resolve itself into the Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union, to consider and act on the national loan bill. Before the question is taken on that motion, I move that general debate on the bill be closed in one hour after its consideration shall be commenced.

Mr. Burnett. I would like to make an inquiry of the gentleman from Pennsylvania. I desire to know whether it is the purpose of the chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means to give a reasonable opportunity for discussion on these important bills before they are voted on ?

Mr. Stevens. I propose to give an hour for the discussion of this bill. I made the motion because I learned that some gentleman on the other side desired to make a speech. I am as willing to accommodate the gentleman on some future bill. I am not disposed to entirely cut gentlemen off.

The question was taken; and the motion limiting debate in the Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union was agreed to.

The House then resolved itself into the Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union, (Mr. Colfax in the chair.)

The CHAIRMAN. The national loan bill is the only one before the committee, and will be taken up for consideration.

Mr. VALLANDIGHAM. I move that the first reading of the bill for information be dispensed with.

The motion was agreed to. The reading of the bill for amendment was commenced.

Mr. VALLANDIGHAM. [Clement Laird Vallandigham (July 29, 1820 - June 17, 1871), Ohio, (D)] Mr. Chairman, in the Constitution of the United States, which the other day we swore to support, and by the authority of which we are here assembled now, it is written:

Mr. VALLANDIGHAM. [Clement Laird Vallandigham (July 29, 1820 - June 17, 1871), Ohio, (D)] Mr. Chairman, in the Constitution of the United States, which the other day we swore to support, and by the authority of which we are here assembled now, it is written:

"All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States."

It is further written also that the Congress to which all legislative powers granted are thus committed—

"Shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press."

And it is yet further written, in protection of Senators and Representatives in that freedom of debate here, without which there can be no liberty, that—

"For any speech or debate in either House they shall not be questioned in any other place."

Holding up the shield of the Constitution, and standing here in the place and with the manhood of a Representative of the people, I propose to myself, to-day, the ancient freedom of speech used within these walls; though with somewhat more, I trust, of decency and discretion than have sometimes been exhibited here. Sir, I do not propose to discuss the direct question of this civil war in which we are engaged. Its present prosecution is a foregone conclusion; and a wise man never wastes his strength on a fruitless enterprise. My position shall at present, for the most part, be indicated by my votes, and by the resolutions and motions which I may submit. But there are many questions incident to the war and to its prosecution, about which I have somewhat to say now.

Mr. Chairman, the President, in the message before us, demands the extraordinary loan of $400,000,000 — an amount nearly ten times greater than the entire public debt, State and Federal, at the close of the Revolution in 1783, and four times as much as the total expenditures during the three years' war with Great Britain, in 1812.

Sir, that same Constitution which I again hold up, and to which I give my whole heart and my utmost loyalty, commits to Congress alone the power to borrow money and to fix the purposes to which it shall be applied, and expressly limits Army appropriations to the term of two years. Each Senator and Representative, therefore, must judge for himself, upon his conscience and his oath, and before God and the country, of the justice and wisdom and policy of the President's demand; and whenever this House shall have become but a mere office wherein to register the decrees of the Executive, it will be high time to abolish it. But I have a right, I believe, sir, to say that, however gentlemen upon this side of the Chamber may differ finally as to the war, we are yet firmly and inexorably united in one thing at least, and that is in the determination that our own rights and dignities and privileges, as the Representatives of the people, shall be maintained in their spirit and to the very letter. And be this as it may, I do know that there are some here present who are resolved to assert and to exercise these rights, with becoming decency and moderation certainly, but at the same time fully, freely, and at every hazard.

Sir, it is an ancient and wise practice of the English Commons, to precede all votes of supplies by an inquiry into abuses and grievances, and especially into any infractions of the constitution and the laws by the Executive. Let us follow this safe practice. We are now in Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union; and in the exercise of my right and my duty as a Representative, and availing myself of the latitude of debate allowed here, I propose to consider THE PRESENT STATE OF THE UNION, and supply also some few of the many omissions of the President in the message before us. Sir, he has undertaken to give us information of the state of the Union, as the Constitution requires him to do; and it was his duty, as an honest Executive, to make that information full, impartial, and complete, instead of spreading before us a labored and lawyerly vindication of his own course of policy — a policy which has precipitated us into a terrible and bloody revolution. He admits the fact; he admits that, to-day, we are in the midst of a general CIVIL WAR, not now a mere petty insurrection, to be suppressed in twenty days by a proclamation and a posse comitatus of three months' militia.

Sir, it has been the misfortune of the President from the beginning, that he has totally and wholly underestimated the magnitude and character of the Revolution with which he had to deal, or surely he never would have ventured upon the wicked and hazardous experiment of calling thirty millions of people to arms among themselves, without the counsel and authority of Congress. But, when at last he found himself hemmed in by the revolution, and this city in danger, as he declares, and waked up thus, as the proclamation of the 15th of April proves him to have waked up, to the reality and significance of the movement, why did he not forthwith assemble Congress, and throw himself upon the wisdom and patriotism of the representatives of the States and of the people, instead of usurping powers which the Constitution has expressly conferred upon us ? ay, sir, and powers which Congress had but a little while before, repeatedly and emphatically refused to exercise, or to permit him to exercise ? But I shall recur to this point again.

Sir, the President, in this message, has undertaken also to give us a summary of the causes which have led to the present revolution. He has made out a case — he might, in my judgment, have made out a much stronger case — against the secessionists and disunionists of the South. All this, sir, is very well as far as it goes. But the President does not go back far enough, nor in the right direction. He forgets the still stronger case against the abolitionists and disunionists of the North and West. He omits to tell us that secession and disunion had a New England origin, and began in Massachusetts in 1804 at the time of the Louisiana purchase; were revived by the Hartford convention in 1814, and culminated, during the war with Great Britain, in sending commissioners to Washington to settle the terms for a peaceable separation of New England from the other States of the Union. He forgets to remind us and the country, that this present revolution began forty years ago, in the vehement, persistent, offensive, most irritating and unprovoked agitation of the SLAVERY QUESTION in the North and West, from the time of the Missouri controversy, with some short intervals, down to the present hour. Sir, if his statement of the case be the whole truth and wholly correct, then the Democratic party and every member of it, and the Whig party, too, and its predecessors, have been guilty for sixty years of an unjust, unconstitutional, and most wicked policy in administering the affairs of the Government.

But, sir, the President ignores totally the violent and long-continued denunciation of slavery and slaveholders, and especially since 1835 — I appeal to Jackson's message for the date and proof — until at last a political anti-slavery organization was formed in the North and West, which continued to gain strength year after year, till at length it had destroyed and usurped the place of the Whig party, and finally obtained control of every free State in the Union, and elected himself, through free-State votes alone, to the Presidency of the United States. He chooses to pass over the fact that the party to which he thus owes his place and his present power of mischief, is wholly and totally a sectional organization; and as such condemned by Washington, by Jefferson, by Jackson, Webster, and Clay, and by all the founders and preservers of the Republic, and utterly inconsistent with the principles, or with the peace, the stability or the existence even, of our Federal system. Sir, there never was an hour, from the organization of this sectional party, when it was not predicted by the wisest men and truest patriots, and when it ought not to have been known by every intelligent man in the country, that it must sooner or later precipitate a revolution and the dissolution of the Union. The President forgets already that, on the 4th of March, he declared that the platform of that party was "a law unto him," by which he meant to be governed in his administration; and yet that platform announced that whereas there were two separate and distinct kinds of labor and forms of civilization in the two different sections of the Union, yet that the entire national domain, belonging in common to all the States, should be taken, possessed, and held by one section alone, and consecrated to that kind of labor and form of civilization alone which prevailed in that section which by mere numerical superiority, had chosen the President, and now has, and for some years past, has had, a majority in the Senate, as from the beginning of the Government it had also in the House. He omits, too, to tell the country and the world — for he speaks, and we all speak now, to the world and to posterity — that he himself and his prime minister, the Secretary of State, declared three years ago, and have maintained ever since, that there was an "irrepressible conflict" between the two sections of this Union; that the Union could not endure part slave and part free; and that the whole power and influence of the Federal Government must henceforth be exerted to circumscribe and hem in slavery within its existing limits.

And now, sir, how comes it that the President has forgotten to remind us, also, that when the party thus committed to the principle of deadly hate and hostility to the slave institutions of the South, and the men who had proclaimed the doctrine of the irrepressible conflict, and who, in the dilemma or alternative of this conflict, were resolved that "the cotton and rice fields of South Carolina, and the sugar plantations of Louisiana, should ultimately be tilled by free labor," had obtained power and place in the common Government of the States, the South, except one State, chose first to demand solemn constitutional guarantees for protection against the abuse of the tremendous power and patronage and influence of the Federal Government, for the purpose of securing the great end of the sectional conflict, before resorting to secession or revolution at all ? Did he not know — how could he be ignorant — that at the last session of Congress, every substantive proposition for adjustment and compromise, except that offered by the gentleman from Illinois, [Mr. Kellog] — and we all know how it was received — came from the South ? Stop a moment, and let us see.

The committee of thirty-three was moved for in this House by a gentleman from Virginia, the second day of the session, and received the vote of every southern Representative present, except only the members from South Carolina, who declined to vote. In the Senate, the committee of thirteen was proposed by a Senator from Kentucky, [Mr. Powell] and received the silent acquiescence of every southern Senator present. The Crittenden propositions, too, were submitted also by another Senator from Kentucky, [Mr. Crittenden] now a member of this House; a man venerable for his years, loved for his virtues, distinguished for his services, honored for his patriotism; for four-and-forty years a Senator, or in other public office; devoted from the first hour of his manhood to the Union of these States; and who, though he him self proved his courage fifty years ago, upon the battle-field against the foreign enemies of his country, is now, thank God, still for compromise at home, to-day. Fortunate in a long and well spent life of public service and private worth, he is unfortunate only that he has survived a Union and, I fear, a Constitution younger than himself.

The Border State propositions also were projected by a gentleman from Maryland, not now a member of this House; and presented by a gentleman from Tennessee, [Mr. Etheridge] now the Clerk of this House. And yet all these propositions, coming thus from tile South, were severally and repeatedly rejected by the almost united vote of the Republican party in the Senate and the House. The Crittenden propositions, with which Mr. Davis, now President of the Confederate States, and Mr. Toombs, his secretary of State, both declared in the Senate that they would be satisfied, and for which every southern Senator and Representative voted, never, on any occasion, received one solitary vote from the Republican party in either House.

The Adams or Corwin amendment, so-called, reported from the committee of thirty-three, and the only substantive amendment proposed from the Republican side, was but a bare promise that Congress should never be authorized to do what no sane man ever believed Congress would attempt to do — abolish slavery in the States where it exists; and yet even this proposition, moderate as it was, and for which every southern member present voted, except one, was carried through this House by but one majority, after long and tedious delay, and with the utmost difficulty — sixty-five Republican members, with the resolute and determined gentleman from Pennsylvania [Mr. Hickman] at their head, having voted against it and fought against it, to the very last.

And not this only, but, as a part of the history of the last session, let me remind you that bills were introduced into this House proposing to abolish and close up certain southern ports of entry; to authorize the President to blockade the southern coast; and to call out the militia and accept the services of volunteers, not for three years merely, but without any limit as to either numbers or time, for the very purpose of enforcing the laws, collecting the revenue, and protecting the public property; and were pressed vehemently and earnestly in this House prior to the arrival of the President in this city, and were then, though seven States had seceded and set up a government of their own, voted down, postponed, thrust aside, or in some other way disposed of, sometimes by large majorities in this House, till at last Congress adjourned without any action at all. Peace then seemed to be the policy of all parties.

Thus, sir, the case stood at twelve o'clock on on the 4th of March last, when, from the eastern portico of this Capitol, and in the presence of twenty thousand of his countrymen, but enveloped in a cloud of soldiery which no other American President ever saw, Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office to support the Constitution, and delivered his inaugural — a message, I regret to say, not written in the direct and straightforward language which becomes an American President and an American statesman, and which was expected from the plain, blunt, honest man of the Northwest, but with the forked tongue and crooked counsel of the New York politician, leaving thirty millions of people in doubt whether it meant peace or war. But whatever may have been the secret purpose and meaning of the inaugural, practically for six weeks the policy of peace prevailed; and they were weeks of happiness to the patriot, and prosperity to the country. Business revived; trade returned; commerce flourished. Never was there a fairer prospect before any people. Secession in the past languished, and was spiritless and harmless; secession in the future was arrested, and perished. By overwhelming majorities, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri all declared for the old Union and every heart beat high with hope that in due course of time, and through faith and patience and peace, and by ultimate and adequate compromise, every State could be restored to it. It is true, indeed, sir, that the Republican party, with great unanimity, and great earnestness and determination, had resolved against all conciliation and compromise. But, on the other hand, the whole Democratic party, and the whole Constitutional-Union party, were equally resolved that there should be no civil war, upon any pretext: and both sides prepared for an appeal to that great and final arbiter of all disputes in a free country — the people.

Sir, I do not propose to inquire, now, whether the President and his Cabinet were sincere and in earnest, and meant, really, to persevere to the end in the policy of peace; or whether, from the first, they meant civil war, and only waited to gain time till they were fairly seated in power, and had disposed, too, of that prodigious horde of spoilsmen and office-seekers which came down, at the first, like an avalanche upon them. But I do know that the people believed them sincere, and cordially ratified and approved of the policy of peace — not as they subsequently responded to the policy of war, in a whirlwind of passion and madness — but calmly and soberly, and as the result of their deliberate and most solemn judgment; and believing that civil war was absolute and eternal disunion, while secession was but partial and temporary, they cordially indorsed, also, the proposed evacuation of Sumter, and the other forts and public property within the seceded States. Nor, sir, will I stop, now, to explore the several causes which either led to a change in the apparent policy, or an early development of the original and real purposes of the Administration. But there are two which I can not pass by. And the first of these was party necessity, or the clamor of politicians, and especially of certain wicked, reckless, and unprincipled conductors of a partisan press. The peace policy was crushing out the Republican party. Under that policy, sir, it was melting away like snow before the sun. The general election in Rhode Island and Connecticut, and municipal elections in New York and in the western States, gave abundant evidence that the people were resolved upon the most ample and satisfactory Constitutional guarantees to the South, as the price of a restoration of the Union. And then it was, sir, that the long and agonizing howl of defeated and disappointed politicians came up before the Administration. The newspaper press teemed with appeals and threats to the President. The mails groaned under the weight of letters demanding a change of policy; while a secret conclave of the Governors of Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, and other States, assembled here, promised men and money to support the President in the irrepressible conflict which they now invoked. And thus it was, sir, that the necessities of a party in the pangs of dissolution, in the very hour and article of death, demanding vigorous measures, which could result in nothing but civil war, renewed secession, and absolute and eternal disunion were preferred and hearkened to before the peace and harmony and prosperity of the whole country.

But there was another and yet stronger impelling cause, without which this horrid calamity of civil war might have been postponed, and, perhaps, finally averted. One of the last and worst acts of a Congress which, born in bitterness and nurtured in convulsion, literally did those things which it ought not to have done, and left undone those things which it ought to have done, was the passage of an obscure, ill-considered, ill-digested, and unstatesmanlike high protective tariff act, commonly known as "The Morrill Tariff." Just about the same time, too, the Confederate Congress, at Montgomery, adopted our old tariff of 1857, which we had rejected to make way for the Morrill act, fixing their rate of duties at five, fifteen, and twenty per cent. lower than ours. The result was as inevitable as the laws of trade are inexorable. Trade and commerce — and especially the trade and commerce of the West — began to look to the South. Turned out of their natural course, years ago, by the canals and railroads of Pennsylvania and New York, and diverted eastward at a heavy cost to the West, they threatened now to resume their ancient and accustomed channels — the water-courses — the Ohio and the Mississippi. And political association and union, it was well known, must soon follow the direction of trade and interest. The city of New York, the great commercial emporium of the Union, and the North-west, the chief granary of the Union, began to clamor now, loudly, for a repeal of the pernicious and ruinous tariff. Threatened thus with the loss of both political power and wealth, or the repeal of the tariff, and, at last, of both, New England — and Pennsylvania, too, the land of Penn, cradled in peace — demanded, now, coercion and civil war, with all its horrors, as the price of preserving either from destruction. Ay, sir, Pennsylvania, the great key-stone of the arch of the Union, was willing to levy the whole weight of her iron upon that sacred arch, and crush it beneath the load. The subjugation of the South — ay, sir, the subjugation of the South! — I am not talking to children or fools; for there is not a man in this House fit to be a Representative here, who does not know that the South can not be forced to yield obedience to your laws and authority again, until you have conquered and subjugated her — the subjugation of the South, and the closing up of her ports — first, by force, in war, and afterward, by tariff laws, in peace — was deliberately resolved upon by the East. And, sir, when once this policy was begun, these self-same motives of waning commerce, and threatened loss of trade, impelled the great city of New York, and her merchants and her politicians and her press — with here and there an honorable exception — to place herself in the very front rank among the worshipers of Moloch. Much, indeed, of that outburst and uprising in the North, which followed the proclamation of the 15th of April, as well, perhaps, as the proclamation itself, was called forth, not so much by the fall of Sumter — an event long anticipated — as by the notion that the "insurrection," as it was called, might be crushed out in a few weeks, if not by the display, certainly, at least, by the presence of an overwhelming force.

These, sir, were the chief causes which, along with others, led to a change in the policy of the Administration, and, instead of peace, forced us, headlong, into civil war, with all its accumulated horrors.

But, whatever may have been the causes or the motives of the act, it is certain that there was a change in the policy which the Administration meant to adopt, or which, at least, they led the country to believe they intended to pursue. I will not venture, now, to assert, what may yet, some day, be made to appear, that the subsequent acts of the Administration, and its enormous and persistent infractions of the Constitution, its high-minded usurpations of power, formed any part of a deliberate conspiracy to overthrow the present form of Federal-republican government, and to establish a strong centralized Government in its stead. No, sir; whatever their purposes now, I rather think that, in the beginning, they rushed, heedlessly and headlong into the gulf, believing that, as the seat of war was then far distant and difficult of access, the display of vigor in re-enforcing Sumter and Pickens, and in calling out seventy-five thousand militia, upon the firing of the first gun, and above all, in that exceedingly happy and original conceit of commanding the insurgent States to "disperse in twenty days," would not, on the one hand, precipitate a crisis, while, upon the other, it would satisfy its own violent partisans, and thus revive and restore the failing fortunes of the Republican party.

I can hardly conceive, sir, that the President and his advisers could be guilty of the exceeding folly of expecting to carry on a general civil war by a mere posse comitatus of three-months militia. It may be, indeed, that, with wicked and most desperate cunning, the President meant all this as a mere entering-wedge to that which was to rive the oak asunder; or, possibly, as a test, to learn the public sentiment of the North and West. But however it may be, the rapid secession and movements of Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee, taking with them, as I have said, elsewhere, four millions and a half of people, immense wealth, inexhaustible resources, five hundred thousand fighting men, and the graves of Washington and Jackson, and bringing up, too, in one single day, the frontier from the Gulf to the Ohio and the Potomac, together with the abandonment, by the one side, and the occupation, by the other, of Harper's Ferry and the Norfolk navy-yard; and the fierce gust and whirlwind of passion in the North, compelled either a sudden waking-up of the President and his advisers to the frightful significancy of the act which they had committed, in heedlessly breaking the vase which imprisoned the slumbering demon of civil war, or else a premature but most rapid development of the daring plot to foster and promote secession, and then to set up a new and strong form of government in the States which might remain in the Union.

But, whatever may have been the purpose, I assert here, to-day, as a Representative, that every principal act of the Administration since has been a glaring usurpation of power, and a palpable and dangerous violation of that very Constitution which this civil war is professedly waged to support. Sir, I pass by the proclamation of the 15th of April, summoning the militia — not to defend this capital — there is not a word about the capital in the proclamation, and there was then no possible danger to it from any quarter, but to retake and occupy forts and property a thousand miles off — summoning, I say, the militia to suppress the so-called insurrection. I do not believe, indeed, and no man believed in February last, when Mr. Stanton, of Ohio, introduced the bill to enlarge the act of 1795, that that act ever contemplated the case of a general revolution, and of resistance by an organized government. But no matter. The militia thus called out, with a shadow, at least, of authority, and for a period extending one month beyond the assembling of Congress, were amply sufficient to protect the capital against any force which was then likely to be sent against it — and the event has proved it — and ample enough, also, to suppress the outbreak in Maryland. Every other principal act of the Administration might well have been postponed, and ought to have been postponed, until the meeting of Congress; or, if the exigencies of the occasion demanded it, Congress should forthwith have been assembled. What if two or three States should not have been represented, although even this need not have happened; but better this, a thousand times, than that the Constitution should be repeatedly and flagrantly violated, and public liberty and private right trampled under foot. As for Harper's Ferry and the Norfolk navy-yard, they rather needed protection against the Administration, by whose orders millions of property were wantonly destroyed, which was not in the slightest danger from any quarter, at the date of the proclamation.

But, sir, Congress was not assembled at once, as Congress should have been, and the great question of civil war submitted to their deliberations. The Representatives of the States and of the people were not allowed the slightest voice in this, the most momentous question ever presented to any government. The entire responsibility of the whole work was boldly assumed by the Executive, and all the powers required for the purposes in hand were boldly usurped from either the States or the people, or from the legislative department; while the voice of the judiciary, that last refuge and hope of liberty, was turned away from with contempt.

Sir, the right of blockade — and I begin with it — is a belligerent right, incident to a state of war, and it can not be exercised until war has been declared or recognized; and Congress alone can declare or recognize war. But Congress had not declared or recognized war. On the contrary, they had, but a little while before, expressly refused to declare it, or to arm the President with the power to make it. And thus the President, in declaring a blockade of certain ports in the States of the South, and in applying to it the rules governing blockades as between independent powers, violated the Constitution.

But if, on the other hand, he meant to deal with these States as still in the Union, and subject to Federal authority, then he usurped a power which belongs to Congress alone — the power to abolish and close up ports of entry; a power, too, which Congress had, also, but a few weeks before, refused to exercise. And yet, without the repeal or abolition of ports of entry, any attempt, by either Congress or the President, to blockade these ports, is a violation of the spirit, if not of the letter, of that clause of the Constitution which declares that "no preference shall be given, by any regulation of commerce or revenue, to the ports of one State over those of another."

Sir, upon this point I do not speak without the highest authority. In the very midst of the South Carolina nullification controversy, it was suggested, that in the recess of Congress, and without a law to govern him, the President, Andrew Jackson, meant to send down a fleet to Charleston and blockade the port. But the bare suggestion called forth the indignant protest of Daniel Webster, himself the arch enemy of nullification, and whose brightest laurels were won in the three years' conflict in the Senate Chamber, with its ablest champions. In an address, in October, 1832, at Worcester, Massachusetts, to a National Republican convention — it was before the birth, or christening, at least of the Whig party — the great expounder of the Constitution, said:

We are told, sir, that the President will immediately employ the military force, and at once blockade Charleston. A military remedy — a remedy by direct belligerent operation, has thus been suggested, and nothing else has been suggested, as the intended means of preserving the Union. Sir, there is no little reason to think that this suggestion is true. We can not be altogether unmindful of the past, and, therefore, we can not be altogether unapprehensive for the future. For one, sir, I raise my voice, beforehand, against the unauthorized employment of military power, and against superseding the authority of the laws, by an armed force, under pretense of putting down nullification. The President has no authority to blockade Charleston.

Jackson! Jackson, sir! the great Jackson! did not dare to do it without authority of Congress; but our Jackson of to-day, the little Jackson at the other end of the avenue, and the mimic Jacksons around him, do blockade, not only Charleston harbor, but the whole Southern coast, three thousand miles in extent, by a single stroke of the pen.

"The President has no authority to employ military force till he shall be duly required" — Mark the word: "required so to do by law and civil authorities. His duty is to cause the laws to be executed. His duty is to support the civil authority."

As in the Merryman case, forsooth; but I shall recur to that hereafter:

His duty is, if the laws be resisted, to employ the military force of the country, if necessary, for their support and execution; but to do all this in compliance only with law and with decisions of the tribunals. If, by any ingenious devices, those who resist the laws escape from the reach of judicial authority, as it is now provided to be exercised, it is entirely competent to Congress to make such new provisions as the exigency of the case may demand.

Treason, sir, rank treason, all this to-day. And, yet, thirty years ago, it was true Union patriotism and sound constitutional law! Sir, I prefer the wisdom and stern fidelity to principle of the fathers.

Such was the voice of Webster, and such too, let me add, the voice, in his last great speech in the Senate, of the Douglas whose death the land now mourns.

Next after the blockade, sir, in the catalogue of daring executive usurpations, comes the proclamation of the 3d of May, and the orders of the War and Navy Departments in pursuance of it — a proclamation and usurpation which would have cost any English sovereign his head at any time within the last two hundred years. Sir, the Constitution not only confines to Congress the right to declare war, but expressly provides that "Congress (not the President) shall have power to raise and support armies;" and to "provide and maintain a navy." In pursuance of this authority, Congress, years ago, had fixed the number of officers, and of the regiments, of the different kinds of service; and also, the number of ships, officers, marines, and seamen which should compose the navy. Not only that, but Congress has repeatedly, within the last five years, refused to increase the regular army. More than that still: in February and March last, the House, upon several test votes, repeatedly and expressly refused to authorize the President to accept the service of volunteers for the very purpose of protecting the public property, enforcing the laws, and collecting the revenue. And, yet, the President, of his own mere will and authority, and without the shadow of right, has proceeded to increase, and has increased, the standing army by twenty-five thousand men; the navy by eighteen thousand; and has called for, and accepted the services of, forty regiments of volunteers for three years, numbering forty-two thousand men, and making thus a grand army, or military force, raised by executive proclamation alone, without the sanction of Congress, without warrant of law, and in direct violation of the Constitution, and of his oath of office, of eighty-five thousand soldiers enlisted for three and five years, and already in the field. And, yet, the President now asks us to support the army which he has thus raised, to ratify his usurpations by a law ex post facto, and thus to make ourselves parties to our own degradation, and to his infractions of the Constitution. Meanwhile, however, he has taken good care not only to enlist the men, organize the regiments, and muster them into service, but to provide, in advance, for a horde of forlorn, worn-out, and broken-down politicians of his own party, by appointing, either by himself, or through the Governors of the States, major-generals, brigadier-generals, colonels, lieutenant-colonels, majors, captains, lieutenants, adjutants, quarter-masters, and surgeons, without any limit as to numbers, and without so much as once saying to Congress, "By your leave, gentlemen."

Beginning with this wide breach of the Constitution, this enormous usurpation of the most dangerous of all powers — the power of the sword — other infractions and assumptions were easy; and after public liberty, private right soon fell. The privacy of the telegraph was invaded in the search after treason and traitors; although it turns out, significantly enough, that the only victim, so far, is one of the appointees and especial pets of the Administration. The telegraphic dispatches, preserved under every pledge of secrecy for the protection and safety of the telegraph companies, were seized and carried away without search-warrant, without probable cause, without oath, and without description of the places to be searched, or of the things to be seized, and in plain violation of the right of the people to be secure in their houses, persons, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures. One step more, sir, will bring upon us search and seizure of the public mails; and, finally, as in the worst days of English oppression — as in the times of the Russells and the Sydneys of English martyrdom — of the drawers and secretaries of the private citizen; though even then tyrants had the grace to look to the forms of the law, and the execution was judicial murder, not military slaughter. But who shall say that the future Tiberius of America shall have the modesty of his Roman predecessor, in extenuation of whose character it is written by the great historian, avertit occulos, jussitque scelera non spectavit.

Sir, the rights of property having been thus wantonly violated, it needed but a little stretch of usurpation to invade the sanctity of the person; and a victim was not long wanting. A private citizen of Maryland, not subject to the rules and articles of war — not in a case arising in the land or naval forces, nor in the militia, when in actual service — is seized in his own house, in the dead hour of the night, not by any civil officer, nor upon any civil process, but by a band of armed soldiers, under the verbal orders of a military chief, and is ruthlessly torn from his wife and his children, and hurried off to a fortress of the United States — and that fortress, as if in mockery, the very one over whose ramparts had floated that star-spangled banner immortalized in song by the patriot prisoner, who, "by dawn's early light," saw its folds gleaming amid the wreck of battle, and invoked the blessings of heaven upon it, and prayed that it might long wave "o'er the land of the free, and the home of the brave."

And, sir, when the highest judicial officer of the land, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, upon whose shoulders, "when the judicial ermine fell, it touched nothing not as spotless as itself," the aged, the venerable, the gentle, and pure-minded Taney, who, but a little while before, had administered to the President the oath to support the Constitution, and to execute the laws, issued, as by law it was his sworn duty to issue, the high prerogative writ of habeas corpus — that great writ of right, that main bulwark of personal liberty, commanding the body of the accused to be brought before him, that justice and right might be done by due course of law, and without denial or delay, the gates of the fortress, its cannon turned towards, and in plain sight of the city, where the court sat, and frowning from its ramparts, were closed against the officer of the law, and the answer returned that the officer in command has, by the authority of the President, suspended the writ of habeas corpus. And thus it is, sir, that the accused has ever since been held a prisoner without due process of law; without bail; without presentment by a grand jury; without speedy, or public trial by a petit jury, of his own State or district, or any trial at all; without information of the nature and cause of the accusation; without being confronted with the witnesses against him; without compulsory process to obtain witnesses in his favor; and without the assistance of counsel for his defense. And this is our boasted American liberty? And thus it is, too, sir, that here, here in America, in the seventy-third year of the Republic, that great writ and security of personal freedom, which it cost the patriots and freemen of England six hundred years of labor and toil and blood to extort and to hold fast from venal judges and tyrant kings; written in the great charter of Runnymede by the iron barons, who made the simple Latin and uncouth words of the times, nullus liber homo, in the language of Chatham, worth all the classics; recovered and confirmed a hundred times afterward, as often as violated and stolen away, and finally, and firmly secured at last by the great act of Charles II, and transferred thence to our own Constitution and laws, has been wantonly and ruthlessly trampled in the dust. Ay, sir, that great writ, bearing, by a special command of Parliament, those other uncouth, but magic words, per statutum tricessimo primo Caroli secundi regis, which no English judge, no English minister, no king or queen of England, dare disobey; that writ, brought over by our fathers, and cherished by them, as a priceless inheritance of liberty, an American President has contemptuously set at defiance. Nay, more, he has ordered his subordinate military chiefs to suspend it at their discretion! And, yet, after all this, he cooly comes before this House and the Senate and the country, and pleads that he is only preserving and protecting the Constitution; and demands and expects of this House and of the Senate and the country their thanks for his usurpations; while, outside of this capitol, his myrmidons are clamoring for impeachment of the Chief Justice, as engaged in a conspiracy to break down the Federal Government.

Sir, however much necessity — the tyrant's plea — may be urged in extenuation of the usurpations and infractions of the President in regard to public liberty, there can be no such apology or defense for his invasions of private right. What overruling necessity required the violation of the sanctity of private property and private confidence? What great public danger demanded the arrest and imprisonment, without trial by common law, of one single private citizen, for an act done weeks before, openly, and by authority of his State? If guilty of treason, was not the judicial power ample enough and strong enough for his conviction and punishment ? What, then, was needed in his case, but the precedent under which other men, in other places, might become the victims of executive suspicion and displeasure ?

As to the pretense, sir, that the President has the Constitutional right to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, I will not waste time in arguing it. The case is as plain as words can make it. It is a legislative power; it is found only in the legislative article; it belongs to Congress only to do it. Subordinate officers have disobeyed it; General Wilkinson disobeyed it, but he sent his prisoners on for judicial trial; General Jackson disobeyed it, and was reprimanded by James Madison; but no President, nobody but Congress, ever before assumed the right to suspend it. And, sir, that other pretense of necessity, I repeat, can not be allowed. It had no existence in fact. The Constitution can not be preserved by violating it. It is an offense to the intelligence of this House, and of the country, to pretend that all this, and the other gross and multiplied infractions of the Constitution and usurpations of power were done by the President and his advisors out of pure love and devotion to the Constitution. But if so, sir, then they have but one step further to take, and declare, in the language of Sir Boyle Roche, in the Irish House of Commons, that such is the depth of their attachment to it, that they are prepared to give up, not merely a part, but the whole of the Constitution, to preserve the remainder. And yet, if indeed this pretext of necessity be well founded, then let me say, that a cause which demands the sacrifice of the Constitution and of the dearest securities of property, liberty, and life, can not be just; at least, it is not worth the sacrifice.

Sir, I am obliged to pass by for want of time, other grave and dangerous infractions and usurpations of the President since the 4th of March. I only allude casually to the quartering of soldiers in private houses without the consent of the owners, and without any manner having been prescribed by law; to the subversion in a part, at least, of Maryland of her own State Government and of the authorities under it; to the censorship over the telegraph, and the infringement, repeatedly, in one or more of the States, of the right of the people to keep and to bear arms for their defense. But if all these things, I ask, have been done in the first two months after the commencement of this war, and by men not military chieftains, and unused to arbitrary power, what may we not expect to see in three years, and by the successful heroes of the fight? Sir, the power and rights of the States and the people, and of their Representatives, have been usurped; the sanctity of the private house and of private property has been invaded; and the liberty of the person wantonly and wickedly stricken down; free speech, too, has been repeatedly denied; and all this under the plea of necessity. Sir, the right of petition will follow next — nay, it has already been shaken; the freedom of the press will soon fall after it; and let me whisper in your ear, that there will be few to mourn over its loss, unless, indeed, its ancient high and honorable character shall be rescued and redeemed from its present reckless mendacity and degradation. Freedom of religion will yield too, at last, amid the exultant shouts of millions, who have seen its holy temples defiled, and its white robes of a former innocency trampled now under the polluting hoofs of an ambitious and faithless or fanatical clergy. Meantime national banks, bankrupt laws, a vast and permanent public debt, high tariffs, heavy direct taxation, enormous expenditures, gigantic and stupendous peculation, anarchy first, and a strong government afterward — no more State lines, no more State governments, and a consolidated monarchy or vast centralized military despotism must all follow in the history of the future, as in the history of the past they have, centuries ago, been written. Sir, I have said nothing, and have time to say nothing now, of the immense indebtedness and the vast expenditures which have already accrued, nor of the folly and mismanagement of the war so far, nor of the atrocious and shameless peculations and frauds which have disgraced it in the State governments and the Federal Government from the beginning. The avenging hour for all these will come hereafter, and I pass by them now.

I have finished now, Mr. Chairman, what I proposed to say at this time upon the message of the President. As to my own position in regard to this most unhappy civil war, I have only to say that I stand to-day just where I stood upon the 4th of March last; where the whole Democratic party, and the whole Constitutional Union party, and a vast majority, as I believe, of the people of the United States stood too. I am for peace, speedy, immediate, honorable peace, with all its blessings. Others may have changed — I have not. I question not their motives nor quarrel with their course. It is vain and futile for them to question or to quarrel with me. My duty shall be discharged — calmly, firmly, quietly, and regardless of consequences. The approving voice of conscience void of offense, and the approving judgment which shall follow "after some time be past," these, God help me, are my trust and my support.

Sir, I have spoken freely and fearlessly to-day, as became an American Representative and an American citizen; one firmly resolved, come what may, not to lose his own Constitutional liberties, nor to surrender his own Constitutional rights in the vain effort to impose these rights and liberties upon ten millions of unwilling people. I have spoken earnestly, too, but yet not as one unmindful of the solemnity of the scenes which surround us upon every side to-day. Sir, when the Congress of the United States assembled here on the 3rd of December, 1860, just seven months ago, the Senate was composed of sixty-six Senators, representing the thirty-three States of the Union, and this House of two hundred and thirty-seven members — every State being present. It was a grand and solemn spectacle — the ambassadors of three and thirty sovereignties and thirty-one millions of people, the mightiest republic on earth, in general Congress assembled. In the Senate, too, and this House, were some of the ablest and most distinguished statesmen of the country; men whose names were familiar to the whole country — some of them destined to pass into history. The new wings of the capitol had then but just recently been finished, in all their gorgeous magnificence, and, except a hundred marines at the navy-yard, not a soldier was within forty miles of Washington.

Sir, the Congress of the United States meets here again to-day; but how changed the scene! Instead of thirty-four States, twenty-three only, one less than the number forty years ago, are here, or in the other wing of the capitol. Forty-six Senators and a hundred and seventy-three Representatives constitute the Congress of the now United States. And of these, eight Senators and twenty-four Representatives, from four States only, linger here yet as deputies from that great South which, from the beginning of the Government, contributed so much to mold its policy, to build up its greatness, and to control its destinies. All the other States of that South are gone. Twenty-two Senators and sixty-five Representatives no longer answer to their names. The vacant seats are, indeed, still here; and the escutcheons of their respective States look down now solemnly and sadly from these vaulted ceilings. But the Virginia of Washington and Henry and Madison, of Marshall and Jefferson, of Randolph and Monroe, the birthplace of Clay, the mother of States and of Presidents; the Carolinas of Pinckney and Sumter and Marion, of Calhoun and Macon; and Tennessee, the home and burial-place of Jackson; and other States, too, once most loyal and true, are no longer here. The voices and the footsteps of the great dead of the past two ages of the Republic linger still — it may be in echo — along the stately corridors of this capitol; but their descendants, from nearly one-half of the States of the Republic, will meet with us no more within these marble halls. But in the parks and lawns, and upon the broad avenues of this spacious city, seventy thousand soldiers have supplied their places; and the morning drum-beat from a score of encampments, within sight of this beleaguered capitol, give melancholy warning to the Representatives of the States and of the people, that amid arms the laws are silent

Sir, some years hence — I would fain hope some months hence, if I dare — the present generation will demand to know the cause of all this; and, some ages hereafter, the grand and impartial tribunal of history will make solemn and diligent inquest of the authors of this terrible revolution.

Mr. HOLMAN. Let me ask the gentleman front Ohio one question before he takes his seat. Is he in favor of the Government suspending its efforts to maintain the integrity of the Union, and of recognizing the so-called seceded States as a separate nationality ? While he censures the policy of the Administration, we would like to know whether he goes with his constituents in demanding that the Constitution must and shall be preserved ?

Mr. VALLANDIGHAM. I will answer the gentleman in the word of a resolution, which I propose to offer at some future time. I ask the Clerk to read it.

The Clerk read, as follows:

Resolved, That the Federal Government is the agent of the people of the several States composing the Union; that it consists of three distinct departments — the legislative, the executive, and the judicial — each equally a part of the Government, and equally entitled to the confidence and support of the States and the people; and that it is the duty of every patriot to sustain the several departments of the Government in the exercise of all the constitutional powers of each which may be necessary and proper for the preservation of the Government in its principles and in its vigor and integrity, and to stand by and defend to the utmost the flag which represents the Government, the Union, and the country.

Mr. Holman. While the gentleman censures the Administration, let me ask him whether, with his own constituents, he is resolved that the Union shall he maintained ?

Mr. VALLANDIGHAM. My votes shall speak for me on that subject. My position is defined in the resolution just read. I am answerable only to my conscience and to my constituents, and not to the gentleman from Indiana.

The CHAIRMAN. The time fixed for general debate has now expired.

The bill was then read through. It provides that the Secretary of the Treasury be authorized to borrow on the credit of the United States, within twelve months from the passage of this act, a sum not exceeding $250,000,000, or so much thereof as he may deem necessary for the public service, for which he is authorized to issue certificates of coupon or registered stock, or Treasury notes, in such proportions of each as he may deem advisable; the stock to bear interest not exceeding seven per cent. per annum, payable semi-annually, irredeemable for twenty years, and after that period redeemable at the pleasure of the United States; and the Treasury notes to be of any denomination fixed by the Secretary of the Treasury, not less than fifty dollars, and to be payable three years after date, with interest at the rate of seven and three-tenths per cent per annum, payable annually on the notes of fifty dollars, and semi-annually on the notes of a larger denomination. And the Secretary of the Treasury may also issue in exchange for coin, and as part of the above loan, or may pay for salaries or other dues from the United States, Treasury notes of a less denomination than fifty dollars, not bearing interest, but payable on demand by the Assistant Treasurers of the United States at Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, or Treasury notes bearing interest at the rate of three and sixty-five hundredths per cent., and exchangeable at any time for certificates of stock, or Treasury notes for fifty dollars and upwards, issued under the authority of this act, and bearing interest as specified above; provided, that no such exchange of such notes in any less amount than $100 shall be made at any one time.

The Treasury notes and certificates of stock, issued under the provisions of this act, shall be signed by the First Comptroller or the Register of the Treasury, and by such other officer or officers of the Treasury as the Secretary of the Treasury may designate; and all such obligations, of the denomination of fifty dollars and upwards shall be issued under the seal of the Treasury Department. The registered stock shall be transferable on the books of the Treasury on delivery of the certificate, and the coupon stock and Treasury notes shall be transferable by delivery. The interest coupons may be signed by such person or persons as may be designated by the Secretary of the Treasury, who shall fix the compensation for the same.

The Secretary of the Treasury shall cause books to be opened for subscription to the Treasury notes for fifty dollars and upwards at such places as he may designate in the United States, and under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe, to be superintended by the assistant treasurers of the United States at their respective localities, and at other places by such depositaries, postmasters, and other persons as he may designate, notice thereof being given in at least two daily papers of this city, and in one or more public newspapers, published in the several places where subscription books may be opened; and subscriptions for such notes may be received from all persons who may desire to subscribe, any law to the contrary notwithstanding; and if a larger amount shall be subscribed in the aggregate than is required at one time, the Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to receive the same, should he deem it advantageous to the public interest; and if not, he shall accept the amount required by giving the preference to the smaller subscriptions; and the secretary of the Treasury shall fix the compensations of the public officers or others designated for receiving said subscriptions; provided, that for performing this or any other duty in connection with this act, no compensation for services rendered shall be allowed or paid to any public officer whose salary is established by law; and the Secretary of the Treasury may also make such other rules and regulations as he may deem expedient touching the installment to be paid on any subscription at the time of subscribing, and further payments by installments or otherwise, and penalties for non-payment of any installment, and also concerning the receipt, deposit, and safe-keeping of money received from such subscriptions until the same can be placed in the possession of the official depositaries of the Treasury, any law or laws to the contrary notwithstanding. And the Secretary of the Treasury is also authorized, if he shall deem it expedient, before opening books of subscription as above provided, to exchange for coin or pay for public dues or for Treasury notes of the issue of 23d of December, 1857, and falling due on the 30th of June, 1861, or for Treasury notes issued and taken in exchange for such notes, any amount of said Treasury notes for fifty dollars and upwards not exceeding $40,000,000.

Before awarding any portion of the loan in stock authorized by this act, the Secretary of the Treasury, if he deem it advisable to issue proposals for the same in the United States, shall give not less than fifteen days' public notice in two or more of the public newspapers in the city of Washington, and in such other places of the United States as he may deem advisable, designating the amount of such loan, the place and the time up to which sealed proposals will be received for the same, the periods for the payment, and the amount of each installment in which it is to be paid, and the penalty for the non-payment of any such installments, and when and where such proposals shall be opened in the presence of such persons as he may choose to attend; and the Secretary of the Treasury is authorized to accept the most favorable proposals offered by responsible bidders; provided, that no offer shall be accepted at less than par.

The Secretary of the Treasury may, if he deem it advisable, negotiate any portion of said loan, not exceeding $100,000,000, in any foreign country, and may issue bonds or certificates of stock for the amount thus negotiated agreeably to the provisions of this act, the interest payable semiannually, either in the United States or at any designated place in Europe; and he is further authorized to appoint such agent or agents as he may deem necessary for negotiating such loan under his instructions and for paying the interest on the same, and to fix the compensation of such agent or agents, and shall prescribe to them all the rules, regulations, and modes under which such loan shall be negotiated, and shall have power to fix the rate of exchange at which the principal shall be received from the contractors for the loan, and the exchange for the payment of the interest in Europe shall be at the same rate.

That whenever any Treasury notes of a denomination less than fifty dollars, authorized to be issued by this act, shall have been redeemed, the Secretary of the Treasury may reissue the same, or may cancel them and issue new notes to an equal amount; provided, that the aggregate amount of stock and Treasury notes issued under the provisions of this act shall never exceed the full amount authorized by the first section of this act; and the power to issue or reissue such notes shall cease and determine after the 31st of December, 1862.

The Secretary of the Treasury shall report to Congress, immediately after the commencement of the next session, the amount he has borrowed under the provisions of this act, of whom, and on what terms, with an abstract of all the proposals, designating those that have been accepted and those that have been rejected, and the amount of stock of Treasury notes that have been issued for the same.

The faith of the United States is solemnly pledged for the payment of the interest and redemption of the principal of the loan authorized by this act; and for the full and punctual payment of the interest the United States specially pledges the duties of impost on tea, coffee, sugar, spices, wines and liquors, and also such excise and other internal duties or taxes as may be received into the Treasury.

All the provision's of the act entitled "An act to authorize the issue of Treasury notes," approved December 23, 1857, so far as the same can or may be applied to the provisions of this act, and not inconsistent therewith, are hereby revived or reenacted.

To defray all the expenses that may attend the execution of this act the sum of $9,00,000, or so much thereof as may be necessary, is appropriated, to be paid out of any money in the Treasury not otherwise appropriated.

Mr. Stevens moved that the committee rise, and report the bill to the House with the recommendation that it do pass.

The motion was agreed to.

So the committee rose; and the Speaker having resumed the chair, Mr. Colfax reported that the Committee of the Whole on the state of the Union had, according to order, had the Union generally under consideration, and particularly House bill No. 14, to authorize a national loan, and for other purposes, and had directed him to report the same back to the House without amendment.

Mr. Stevens demanded the previous question on the engrossment and third reading of the bill.

The previous question was seconded, and the main question ordered; and under the operation thereof, the bill was ordered to be engrossed and read a third time; and being engrossed, it was accordingly read the third time.

Mr. ASHLEY demanded the yeas and nays on the passage of the bill.

The yeas and nays were ordered.

The question was taken; and it was decided in the affirmative— yeas 150, nays 5; as follows:

YEAS— Messrs. Aldrich, Allen, Alley, Ancona, Arnold, Ashley, Babbitt, Goldsmith F. Bailey, Joseph Bailey, Baker, Baxter, Beaman, Bingham, Francis P. Blair, Samuel S. Blair, Blake, George H. Browne, Buffinton, Calvert, Chamberlain, Ambrose W. Clark, Cobb, Colfax, Frederick A. Conkling, Roscoe Conkling, Conway, Cooper, Covode, Cox, Cravens, Crisfield, Crittenden, Curtis, Cutter, Davis, Dawes, Delano, Divan, Duell, Dunlap, Dunn, Edgerton, Edwards, Eliot, Fly, English, Fenton, Fessenden, Fisher, Fouke, Franchot, Frank, Gooch, Granger, Grider, Gurley, Haight, Hale, Harding, Harrison, Hickman, Holman, Horton, Hutchins, Jackson, Johnson, Julian, Kelley, Francis W. Kellogg, William Kellogg, Lansing, Law, Lazear, Leary, Lehman, Logan, Loomis, Lovejoy, McClernand, McKean, McKnight, Mallory, Menzies, Mitchell, Moor head, Anson P. Morrill, Justin S. Morrill, Morris, Nixon, Noble, Noell, Nugen, Odell, Olin, Patton, George H. Pendleton, Perry, Pike, Pomeroy, Porter, Potter, Alexander H. Rice, John H. Rice, Richardson, Riddle, Robinson, Edward H. Rollins, James S. Rollins, Sedgwick, Shank, Sheffield, Shellabarger, Sherman, Sloan, Spaulding, John B. Steele, William G. Steele, Stevens, Stratton, Benjamin F. Thomas, Francis Thomas, Thayer, Train, Trimble, Trowbridge, Upton, Vandever, Van Horn, Van Valkenburgh, Van Wyck, Verree, Vibbard, Voorhees, Wadsworth, Wall, Wallace, Charles W. Walton, E.P. Walton, Wand, Washburne, Webster, Wheeler, Whaley, Albert S. White, Chilton A. White, Wickliffe, Windom, Woodruff, Worcester, and Wright —150.

NAYS— Messrs. Burnett, Norton, Reid, Vallandigham, and Wood— 5.

So the bill was passed. During the vote, Mr. Moorhead stated that Mr. Carlile was confined to his room by illness.

The vote was announced, as above recorded. Mr. Stevens moved to reconsider the vote by which the bill was passed; and also moved that the motion to reconsider be laid upon the table. The latter motion was agreed to.

____________________________

In the Senate

July 13, 1861.

THE LOAN BILL.

Mr. FESSEDEN. I am directed by the Committee on Finance, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. No. 14) to authorize a national loan, and for other purposes, to report it back to the Senate with some few amendments. It is very important that this bill should be disposed of as soon as possible; and as the amendments to it are mostly verbal, with one exception, which will be easily understood by the Senate, I ask the unanimous consent of the Senate to consider the bill now.

There being no objection, the Senate, as in Committee of the Whole, proceeded to consider the bill (H.R. No.14) to authorize a national loan, and for other purposes.

The bill provides for a loan of $250,000,000, in the manner suggested in the report of the Secretary of the Treasury.

The first amendment of the Finance Committee was in line eight of section one, to strike out the words "certificate of," and after "coupon" insert "bonds;" so as to make it read:

For which he is authorized to issue coupon bonds.

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was, in the ninth line of the first section, to strike out "stock," and insert "bonds."

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was, in line ten of the same section, to strike out "stock," and insert "bonds."

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line sixteen of the same section, to strike out " three years after," and insert "at the pleasure of the United States at any time after three years;" so as to make the clause read:

The Treasury notes to be of any denomination fixed by the Secretary of the Treasury, not less than fifty dollars, and to be payable at the pleasure of the United States at any time after three years.

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in the same section, line twenty-six, to insert "payable in one year from date;" so as to make the clause read:

And the Secretary of the Treasury may also issue, in exchange for coin and as part of the above loan, or may pay for salaries or other dues from the United States, Treasury notes of a less denomination than fifty dollar, not bearing interest, but payable on demand by the assistant treasurers of the United States at Philadelphia, New York, or Boston, or Treasury note, hearing interest at the rate of three and sixty-five hundredths per cent., payable in one year from date.

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line twenty-seven of the sane section, to strike out "certificates of stock;" so as to make it read:

Or Treasury notes, bearing interest at the rate of three and sixty-five hundredths per cent., payable in one year from date, and exchangeable at any time for Treasury notes for fifty dollars and upwards, &c.

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line twenty-eight of the same section, to strike out "issued," and insert "issuable."

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line thirty of the same section, to strike out "such" before "exchange."

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in section two, line two, to strike out "certificates of stock," and insert "bonds."

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line three of section two, to insert "or second" after "first;" so as to make it read:

That the Treasury notes and bonds issued under the provision, of this act shall be signed by the First or Second Comptroller, or the Register of the Treasury, &c.

The amendment was agreed to.

The next amendment was in line four of section two, offer the word "and," to insert "countersigned;" so as to read: