Reduction of Currency, Increase of Debt

--- An Act to amend an Act entitled "An Act to provide Ways and Means to support the Government," approved March third, eighteen hundred and sixty-five.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the act entitled "An act to provide ways and means to support the Government" approved March third, eighteen hundred and sixty-five, shall be extended and construed to authorize the Secretary of the Treasury, at his discretion, to receive any Treasury notes or other obligations issued under any act of Congress, whether bearing interest or not, in exchange for any description of bonds authorized by the act to which this is an amendment; and also to dispose of any description of bonds authorized by said act, either in the United States or elsewhere, to such an amount, in such manner, and at such rates as he may think advisable, for lawful money of the United States, or for any Treasury notes, certificates of indebtedness, or certificates of deposit, or other representatives of value, which have been or which may be issued under any act of Congress, the proceeds thereof to be used only for retiring Treasury notes or other obligations issued under any act of Congress; but nothing herein contained shall be construed to authorize any increase of the public debt: Provided, That of United States notes not more than ten millions of dollars may be retired and cancelled within six months from the passage of this act, and thereafter not more than four millions of dollars in any one month: And provided further, That the act to which this is an amendment shall continue in full force in all its provisions, except as modified by this act.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the act entitled "An act to provide ways and means to support the Government" approved March third, eighteen hundred and sixty-five, shall be extended and construed to authorize the Secretary of the Treasury, at his discretion, to receive any Treasury notes or other obligations issued under any act of Congress, whether bearing interest or not, in exchange for any description of bonds authorized by the act to which this is an amendment; and also to dispose of any description of bonds authorized by said act, either in the United States or elsewhere, to such an amount, in such manner, and at such rates as he may think advisable, for lawful money of the United States, or for any Treasury notes, certificates of indebtedness, or certificates of deposit, or other representatives of value, which have been or which may be issued under any act of Congress, the proceeds thereof to be used only for retiring Treasury notes or other obligations issued under any act of Congress; but nothing herein contained shall be construed to authorize any increase of the public debt: Provided, That of United States notes not more than ten millions of dollars may be retired and cancelled within six months from the passage of this act, and thereafter not more than four millions of dollars in any one month: And provided further, That the act to which this is an amendment shall continue in full force in all its provisions, except as modified by this act.

Sec. 2. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Treasury shall report to Congress at the commencement of the next session the amount of exchanges made or money borrowed under this act, and of whom, and on what terms; and also the amount and character of indebtedness retired under this act, and the act to which this is an amendment, with a detailed statement of the expense of making such loans and exchanges.

APPROVED, April 12, 1866.

Thirty-Ninth Congress

First Session

December 4, 1865 to July 28, 1866.

House of Representatives

Friday, March 16, 1866.

LOAN BILL.

The House resumed the consideration of the special order, House bill No. 207, to amend an act entitled "An act to provide ways and means to support the Government," approved March 3, 1865.

The pending question was upon the motion of Mr. Morrill to strike out the following words:

Provided, That the bonds which may be disposed of elsewhere than in the United States may be made payable, both principal and interest, in the coin or currency of the country in which they are made payable, but shall not bear a rate of interest exceeding five per cent. per annum.

The SPEAKER. On this bill the gentleman from Maine [Mr. Pike] is entitled to the floor.

Mr. Morrill. With the consent of the gentleman from Maine, I desire to state that it is the purpose of the Committee of Ways and Means to ask for decisive action upon this bill to-day; and unless the discussion should previously be exhausted, I shall ask the previous question either this afternoon or this evening.

Mr. Washburne, of Illinois. I hope that we shall agree to take the vote this afternoon, so as to avoid the necessity for an evening session.

The SPEAKER. Will the gentleman from Vermont state at what time he intends to claim the floor to ask the previous question ?

Mr. Morrill. I think about quarter past four o'clock this afternoon.

Mr. PIKE. I hold in my hand an amendment, which, if it be not now in order, I will offer at a proper time. It is to add to the bill the following additional proviso:

Provided further, That except for the purpose of discharging existing legal obligations, all bonds issued under and by virtue of this act, or of the act approved March 3, 1865, to which this is additional, shall be subject to the same State and municipal taxation as other property of like value.

The SPEAKER. That amendment is not in order at present. An amendment offered yesterday by the gentleman from Vermont [Mr. Morrill] is now pending. Any other amendment, to be in order now, must be in the shape of an amendment to an amendment, and must be germane to the pending amendment.

Mr. PIKE. [Frederick Augustus Pike (December 9, 1816 – December 2, 1886) (R) Maine, voted for reduction of currency] Mr. Speaker, in common with the rest of the House, I enjoyed exceedingly on yesterday the strong popular breeze from the Chicago district. The gentleman from Illinois [Mr. Wentworth] gave us in graphic terms and in most emphatic manner the opinions of his constituency upon the pending measures of finance, and urged upon us all the absolute necessity of sticking to our constituencies under any and all circumstances. I hail the distinguished gentleman as a most efficient coworker.

Mr. Wentworth. I spoke for myself, and not for anybody else.

Mr. PIKE. The gentleman, I presumed, spoke also for his constituency; but if his constituents do not agree with him it is his concern and not mine.

The only objection I have ever heard to the amendment I propose is that it smacks too much of the constituency. It is said, incorrectly I think, to place the interests of the constituency above the interests of the General Government — if it be possible to separate the two — and that it contravenes the doctrine that on all occasions it is proper to subordinate the interests of the part to the interests of the whole, and for that reason is objectionable. But the doctrine of the gentleman from Illinois overrides all such objections at once and makes an answer unnecessary. I count upon him with confidence in support of my amendment. And with equal assurance I reckon upon his support, upon the same principle, of the people's paper now afloat. I know that his constituency, like mine, are satisfied with the "greenback" circulation. They have no desire for change. They do not wish to swap it off for any bank paper, however good. There is not a man in this country, in the Chicago district or in mine, or in any other, that prefers the bank note to the "greenback." All of them, "without regard to race or color," are content with the money to which they have become accustomed and which costs the Government nothing but the expense of making. They do not believe in the thrift of the bargain which would exchange this paper for an inferior one, and the only boot to be got is the luxury of paying interest ! Certainly the gentleman from Illinois [Mr. Wentworth] cannot countenance such a scheme as that. He will not desert his constituency in a matter of such importance.

Mr. Wentworth. Does the gentleman think it is right to pay our soldiers in money below par when the Government can borrow money at six per cent. interest ?

---[Oh the tortured logic of the protector of soldiers' and poor people's interest ! These soldiers become tax-payers the next day, and for the next 20 years have to pay for that borrowed money with which you paid them ! Who is the thief, who is the repudiator ?]

Mr. PIKE. No. I would have them paid in the best money in the world, the "greenbacks." I have no idea of paying them in bank currency when we can give them Government notes. I make no attempt to follow the distinguished gentleman in his argument. I have no quarrel with him on the score of the evils of a depreciated currency. Congress entered upon the sea of irredeemable paper knowing the danger of the voyage it was about to take. It was fully warned by gentlemen on the other side of the House, as well as on ours. Vallandigham and his associates exhibited the most intense zeal. We heard then, as yesterday, a full description of John Law and the French assignats and mandats, and the Russian roubles, and all other paper that ever went under par. And predictions were freely made that the paper would become as worthless as the old continental, when a hundred dollars were freely given for a breakfast. And still Congress tried the experiment. I recollect that the first speech I ever had the honor of making in Congress was in advocacy of the legal-tender clause of the loan bill of 1862. Great evils have undoubtedly come of that action. Some of them were described yesterday by the gentleman from Illinois. But greater evils were avoided. When the historian shall calmly strike the balance he will say the action of Congress was wise. For one, although no financier, I am satisfied with it. My constituency is satisfied with it. The country at large has given no evidence that it does not deem our action praiseworthy.

Whatever may be done hereafter, it is quite sure that the paper issued by the Government and made a legal tender will always be considered one of the efficient agencies in carrying on the war. It is entitled to the gratitude of the Republic for the good it has accomplished.

Nor have I anything to say in reply to the attack on gold brokers and gamblers. The gentleman from Illinois represents a large, and thriving city. Such people abound in cities. I presume he knows much more about them than I do. There are none in my district, and I know nothing of their interests in this bill, whether for it or against it. But this I do know. If we attempt to legislate either for or against the interests of that class of people, except to tax them, Congress will be engaged in a very thriftless pursuit. There are as many of them interested in a fall of gold as in a rise. One set of men bets on a fall of gold, and of course the other set bets on an advance. And so it goes on from day to day, and hour to hour. Instead of watching the fluctuations of the market and attempting to adapt legislation to the interests of one class or the other, I choose rather to follow the teachings of the gentleman and legislate for my constituents.

Sir, the problem to be solved by the bill before the House is the proper method of returning most expeditiously to specie payments. True policy — such policy as was approved by the House by its resolution of the 18th of December — would lead the country back to gold and silver by the shortest practicable road. The Committee of Ways and Means present this bill as their method of compassing the desired end.

It provides that the Secretary of the Treasury shall have full control of the currency of the country, and by direct inference of the market values of every description of property. Invested with the powers conferred by this bill he may lessen the volume of currency when he pleases and how. He may sell between seven or eight hundred millions of bonds at such price and time and on such terms as he will. The money he receives for them he may hold in such quantities as he chooses, or he may issue it again. If he does not get back to specie payment speedily; it will not be for lack of authority.

The Secretary of State said of the Freedmen's Bureau in his address to the people of New York that its powers were tendered to the President "too hastily by a too confiding Congress." Those were powers over the Army for the pacification of a large section of the Union and the protection of the right of labor. The power conferred by this bill is still greater in its way over the monetary affairs of the country. The London Times said of the able report of the Secretary of the Treasury at the commencement of the session, that it was remarkable for the confidence it invited Congress to place in the Executive. This bill is drawn in accordance with that idea.

During the war the Secretary was necessarily invested with large powers, and now it is proposed in the first bill presented since the return of peace to continue the same authority.

I do not know that I should object to the bill simply on that account. I have great confidence in the integrity of the Secretary and his ability in the management of financial matters. Whether in the whirl of political affairs he will remain in his present position, or whether he will be succeeded by some one whose fitness for the place is less apparent, who can say ? He is subject to all the accidents of political life, and they are not few. I confess I should rest easier under the passage of this bill if I had some guarantee of the Secretary's tenure

of office. Still, if the object to be obtained is worth the risk, I shall not be found objecting. How is it ?

The bill proceeds upon the assumption that it is absolutely necessary to force the contraction of the currency. But is this beyond question ? The ordinary course of business transactions tends rapidly in that direction. Is it clear that they are not sufficiently urgent and effective ? There has been nervousness in the country at the slow progress made toward specie, and without thought people urge the contraction of the currency as the only remedy.

But such persons should consider that we now have in the country as much currency authorized by law as we have ever had, and still we have gone a long way toward resumption of specie payments. Without by legislation contracting the currency a single dollar we have run gold down from 287 to 130. In this we follow the example of England, where it is well known that specie payments were resumed, after their long suspension during the Napoleonic wars, without material contraction of the currency.

The last returns of the national banks give an increased authorized circulation. This added to the United States currency, no part of which has been withdrawn, gives the amount now permitted by law as greater to-day than ever before, and still gold is declining.

How can it be said, when more than three quarters of the journey toward specie has been made under such circumstances, that it is impossible to do the rest of it ?

If then it is not absolutely necessary by law to lessen the quantity of paper afloat in order to compass this desirable end, is it wise to make the attempt by legal coercion ? Is there not danger that more harm shall come to the business interests of the country by legislative interference than good to the currency ? There would be no difficulty in causing distress and making great disturbance in the business world, but having done that shall we have accomplished a good thing ? Without special legislation to that end, and in the ordinary course of Treasury receipts and disbursements, we are approaching specie payments, perhaps rapidly enough. Time should be reckoned an element of reform in the currency as well as in the bodypolitic, and it may be that we get on as fast in this moderation of action as if we took more violent measures to attain our end. Suppose the Secretary, acting under our authority, should make a violent contraction of the currency, would not the clamor of the mercantile world drive him back from his purpose ? And an attempt made and failing would probably discourage the next, and thus we should be thrown back of the starting-point. We see now there is great caution manifested in entering upon new schemes; very much more than a year ago. The country realizes the fact that sooner or later we shall come to specie payments. When that time does come there will be a large decline in prices. Business men "discount" this knowledge. Thus, in the natural course of trade the end approaches. Is it not probable that in this way we shall get what we wish sooner than by constraint and legislative coercion ?

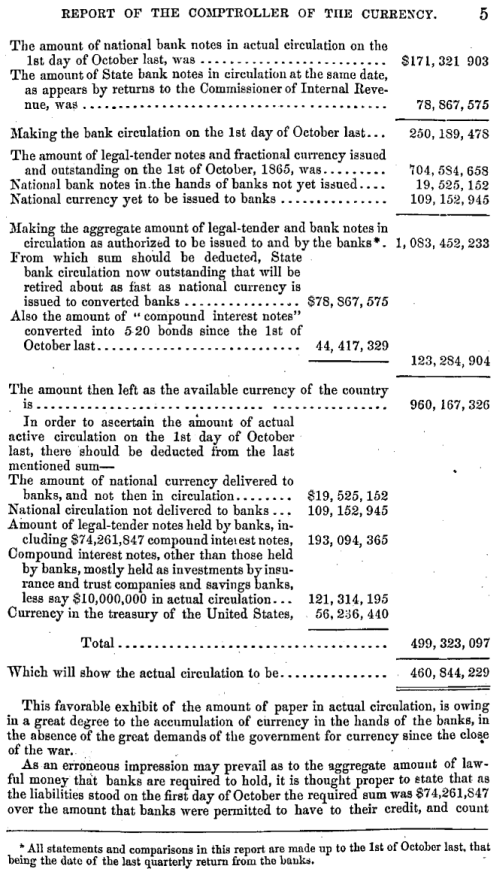

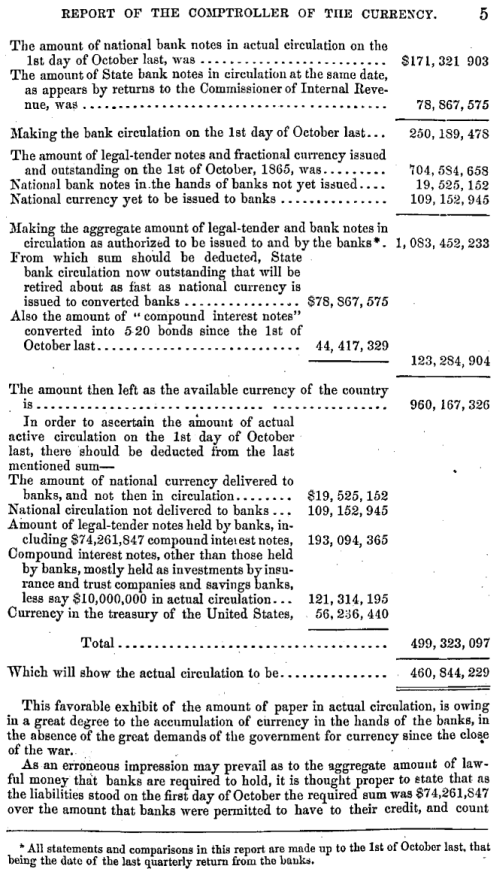

The Comptroller of the Currency, in his report, sums up the authorized currency of the country and then attempts to reckon the amount in actual use. The two footings differ very greatly. He says:

"This favorable exhibit of the amount of paper circulation is owing in a great degree to the accumulation of currency in the hands of the banks in the absence of the great demands of the Government for currency since the close of the war."

We should do well to recollect this. It states a fact of importance. The banks hold an abundance of currency that is not called for. In other words, trade knows its own needs. It was so before the war. Legislation did not fix the amount of circulation. There was no difficulty in obtaining from State Legislatures authority to issue bills. Charters could be got anywhere for the asking. But men who dealt in money found they needed something more than legislative authority. They were constantly brought to the test of being able to pay the notes they put out, and this kept them in check. So now we still act with reference to the laws of trade, even under suspension of specie payments. Those laws are steadily bringing us back to specie. The question is whether we shall be a little patient pending their action. Meantime we have one fact of some little moment to reconcile us to the present condition of affairs: corporate debts are being discharged in the depreciated currency in which they were contracted. This is of consequence to debtors, and I do not know but they are entitled to some little consideration at the hands of the Government. The Government forced our people to contract municipal debts to a large amount in order to comply with the demands made upon them to assist the Republic in the time of its distress, and for one I shall not regret if one of the consequences of postponement of specie payment shall be that by heavy municipal taxation they free themselves from those enforced obligations in the depreciated currency they received. By general consent they seem everywhere to be making the attempt. And, notwithstanding what has been said so positively, it may be found after some delay that the currency of the country in actual use is not in excess of business wants. It may be that the business of the country knows better than we think what are its own needs.

I read the opinions of well-established authority in finance with great interest; but the shrewdest have been so much mistaken that they ought not to expect public confidence without some discount. When we entered the war they all predicted financial ruin, but it did not come; and when the war closed they were equally certain that lassitude and business stagnation must follow, but they blundered again. These blunders of professional men give the rest of us a right to entertain and express our views, or at least to hold them with some little confidence. The worst that can happen to us is that we shall be mistaken as others have been.

In reckoning the absolute amount of currency needed we should bear in mind that the Secretary then demonstrated in one of his reports that gold was "demonetized" by congressional action and should be thrown out of account. He maintained that gold and silver should not be considered in the circulation until specie payments are resumed. This necessitates increased paper.

In addition to this is the enlarged volume of trade everywhere. The agricultural productions of the country, as a whole, are greater than ever before. Manufactures have swollen beyond any previous figures. Wholly new sources of natural wealth are developed. Population increases. Larger capacity of transportation by water and by land is demanded. All this requires more money.

Nor will it do to ignore the changes made within a few years in the methods of trade. The uncertainty of the currency, while doing much injury, erected the good result of prompter payments. Men carry their money now in their pocket-books and pay for what they buy. Formerly they purchased on credit, and their credits in the shape of notes of themselves furnished a sort of currency of the meanest kind. This change calls for still more paper.

And how much currency have we now afloat ? This would seem to be a simple matter of arithmetic. But authoritative opinions differ.

The President in the annual message says:

"Five years ago the bank-note circulation of the country amounted to not much more than two hundred millions; now the circulation, bank and national, exceeds seven hundred millions. The simple statement of the fact recommends, more strongly than any word of mine could do, the necessity of our restraining this expansion."

The Secretary of the Treasury gives the figures as follows:

"The paper circulation of the United States on the 31st or October last was substantially as follows:

1. United States notes and fractional currency ....... $454,218,038.20

2. Notes of the national banks .......... 185,000,000.00

3. Notes of State banks, including outstanding issues of State banks converted into national banks .......... 65,000,000.00

....................... $704,218,038.20

"The amount of notes furnished to the national banks up to and including the 31st of October was a little over $205,000,000, but it is estimated that $20,000,000 of these had not then been put into circulation.

"In addition to the United States notes, there were also outstanding $52,536,900 five per cent. Treasury notes and $173,012,140 compound-interest notes, of which it would doubtless be safe to estimate that $30,000,000 were in circulation as currency.

"From this statement it appears that, without including seven and three-tenths notes, many of the small denominations of which were in circulation as money, and all of which tend in some measure to swell the inflation, the paper money of the country amounted, on the 31st of October, to the sum of $734,218,038.20, which has been daily increased by the notes since furnished to the national banks, and is likely to be still further increased by those to which they are entitled, until the amount authorized by law ($300,000,000) shall have been reached, subject to such reduction as may be made, by the withdrawal of the notes of the State banks."

The Comptroller of the Currency hugs the detail of the case a little closer. He gives the actual situation thus:

The amount of national bank notes in actual circulation on the 1st day of October last was ..... $171,321,903

The amount of State bank notes in circulation at the same date, as appears by returns to the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, was .............. 78,867,575

Making the bank circulation on the 1st day of October last ....... 250,159,475

The amount of legal-tender notes and fractional currency issued and outstanding on the 1st of October, 1865, was ..... 704,584,658

National bank notes in the hands of banks not yet, issued ..... 19,525,152

National currency yet to be issued to banks .......... 109,152,945

Making the aggregate amount of legal-tender and bank notes in circulation as authorized to be issued to and by the banks ....... 1,083,452,233

From which sum should be deducted, State bank circulation now outstanding that will be retired about as fast as national currency is issued to converted banks ......... $78,867,575

Also the amount of "compound interest notes" converted into five-twenty bonds since the 1st of October last ....... 44,417,329

................. 123,284,904

The amount then left as the available currency of the country is ........ 960,167,329

In order to ascertain the amount of actual active circulation on the 1st day of October last, there should be deducted from the last mentioned sum—

The amount of national currency delivered to banks, and not then in circulation ......... $19,525,152

National circulation not delivered to banks. ...... 109,152,945

Amount of legal-tender notes held by banks, including $74,261,847 compound-interest notes ..... 193,094,365

Compound-interest notes, other than those hold by banks, mostly held as investments by insurance and trust companies and savings banks, less say $10,000,000 in actual circulation .......... 121,314,195

Currency in the Treasury of the United States ..... 56,236,440

............. 499,323,097

Showing the actual circulation to be ...... $460,844,232

I do not cite these differences simply because of the variance of the results. If that were all, I should take the figures of the Secretary as the head of the Department and a gentleman in whom I have entire confidence. But that is not all. The mode of getting at the circulation is what I call attention to. In the one case it is the authorized circulation, and in the other the actual circulation. And in this particular it is not unlike the different modes of calculating the expenditures of the Government during the war. The opponents of the war took the total of the gross appropriations. They paraded these, and told the country to look at the enormous figures. It was an ingenious method of stating facts. So now, when we speak of inflation, we must not confound the two. The Secretary is right, and the Comptroller is right. But it is with the "actual circulation" we have to do, because it is that which affects the country.

The country offers to the business men of the country nearly eight hundred millions of currency. Business does not need so much, and takes but five hundred millions. Is it not somewhat arrogant for Congress to say that it knows very much better than business what it needs ? And can anybody demonstrate that the actual circulation of the country, as given by the Comptroller, is in excess ? Compare it with the former circulation, and take into account the circumstances I have enumerated, and say whether the proposition that we have too large a volume of currency in actual use is a clear one; or compare with the amount in circulation in Great Britain and France. Mr. Carey gives the amount in circulation in France as $1,070,000,000, or nearly thirty dollars per head; and in Great Britain as $700,000,000, or about twenty-five dollars per head. There are many reasons why our circulating medium should be as great as that of either of these countries.

The fullness of price for merchandise is generally deemed positive proof of excessive currency. But how much is due to that, and how much to the waste of war, to accidental short supply or excessive demand or large taxation, is not well settled. Corn is at the old gold price; wheat is above it. There is a full stock of one and not of the other. Foreign goods ran high and cannot be cheap on gold so long as the present tariff hold. As we go toward specie some articles recede rapidly in price and some do not. I presume nobody expects under the great influx of gold and taxation to see the whole list of prices average as low as it was before the war. If they do they will be disappointed. The present generation will live its life out on high prices.

It seems to me, sir, that the great demand for legislation upon this subject arises out of apprehension of future trouble. It is supposed that the trade of the country will become deranged. But the country has survived many apprehended crises, even during my day, and while I would not shut my eyes to real evils that were impending and might be avoided, I would try hard not to be too greatly disturbed by fancied ones. Almost every gentleman on the floor knows that his constituents up to this time have been unusually prosperous. How long this state of things will continue who knows ? And although it is said with much earnestness that this apparent prosperity is unreal and delusive, yet I know that all over the country people would be very glad to make the delusion perpetual, and seriously, is it worthwhile in the present condition of affairs, when the tendency of things is all right, to interpose, and for the purpose of avoiding a supposed catastrophe run the risk of hurrying the country into commercial difficulties that may be serious ? I know the theories that prevail on the subject. It is theoretically impossible that the present state of things should continue. But I know, also, that it was theoretically impossible that it should exist now; and it may be in this day of strange things that financial wonders may follow in close company with the political oddities that abound. I am quite disposed to try it. We all know the man who, upon demonstrating his theory, was told the facts were against him. "So much the worse for the facts," said he. It will hardly do to follow his example in finance. I am willing to let theories slide and stick to facts.

But supposing it to be necessary to reduce the volume of currency, when shall we begin ? Take the resolution of December 18 and construe it to mean contraction of the currency irrespective of everything else, and what then ? The gentleman from Illinois yesterday paraded that resolution at large as if he had the House in a trap and took great satisfaction in springing it. But the most he can make of the resolution is "contraction of the currency." Properly construed it means that the House approve such speedy contraction as business interests will permit. But if it be absolute and immediate contraction, how shall we proceed ? We have now three currencies in the country, and they are, as authorized by law, nearly as follows:

United States currency, consisting of greenbacks and postage ...... $450,959,107

National bank circulation ................... 257,072,910

State bank circulation, about ............... 60,000,000

Total .................................... $768,032,017

By general consent the State bank circulation is to be counted out. These worthy institutions are done. They have been destroyed for the benefit of this great brood of national banks. And the important question before the House is whether when the currency is lessened it shall be by cutting off national bank notes or by withdrawing "greenbacks." Is there anything in the resolution that settles this point ?

The evident design of this bill is to strike at the greenback currency and leave the other in full volume. Why ? Is the bank circulation any better or more convenient than the "greenback?" Surely nobody will say that so long as its only legal value consists in its convertibility on demand into "greenbacks." Will the withdrawal of a hundred million "greenbacks" hasten specie payments any more rapidly than retiring an equal amount of bank currency ? To say this is to say that it will take more specie to redeem a given amount of "greenbacks" than it will to redeem the same amount of bank currency, for specie payments are not resumed until complete convertibility is established for all kinds of currency. If we could strike out of existence the $317,072,910 of bank circulation it would be just as easy a task to make the remaining "greenbacks" convertible as it would to make the banks specie paying if so many United States notes had been withdrawn. It would be easier. The country never had a currency with which it was so well satisfied as with this. And when the day comes for the announcement that the Government is ready to pay gold and silver for its notes there will be no rush to make the exchange. There will be no element of distrust as to ultimate payment from which banks suffer in time of panic, and no individual will take the trouble to exchange convenient paper for inconvenient gold unless he be engaged in foreign trade or wishes it for special purpose.

Of course there can be but one way to "resume specie payments." Those whose notes are out must strengthen themselves with specie, so as to pay such as are presented for payment. The national banks now have a large circulation, with very little specie. Out of the large cities, the first thing a State bank does when it becomes national is to sell its specie. The Government has about one dollar of specie for every ten of circulation. Of course if the Government sets itself steadily at work accumulating specie, and at the same time represses bank circulation, it would not be a great while before it would be in a state to make the announcement that it was ready to pay specie on demand.

The Secretary seems now to be engaged in selling gold largely, for the double purpose of obtaining the premium and depressing the price of gold. I hope he may succeed in his experiment. If he does not he can take the opposite course and hoard gold, with the avowed purpose of continuing to do so until he has enough on hand to warrant a resumption. This course, if persisted in, will accomplish the purpose, and meantime the banks will take notice of his movements and withdraw their own circulation for the purpose of preparing themselves for the demands that will be made upon them. Thus all parties would work together to hasten the advent of specie payments. But before that time the course of business and good management of public affairs must have established full confidence in the public mind that the permanent revenue of the country will meet the permanent expenditure and leave a small margin for lessening the principal year by year. When there is no doubt of the continuance of this state of things specie will have lost its peculiar value. Of course confidence will come. Sooner or later we are to pay specie to every man who wants it in exchange for the Government note he holds. But the conditions must first be fulfilled. We shall have no such result as this without having gone through the proper preparation. This fruit will not be gathered without the precedent cultivation. Why, then, make discrimination against the Government note and in favor of the bank note ? Ought we to do it out of special favor to the banks ?

I have sometimes feared that these national banks were pet creations, to be favored at the expense of the public interest. They frequently pay large dividends from public deposits. They are ingenious enough to hold interest-bearing legal tenders and thus make the Government pay interest for the money it places in their custody. It is a business more profitable to the banks than to the Government. And although national bank stock rules high, and large dividends are made in all quarters of the country, still the stockholders in these patriotic institutions are resisting taxation, and combine in the endeavor to extort from the Supreme Court a decision that their stock shall be exempt from the burdens of taxation which oppress the property of every man in the country. And having obtained that, if they could also compass a monopoly of the banking business of the country, their greed would be in a fair way of satisfaction. An avaricious man, even, might be well satisfied with banking property exempt from both taxation and competition. I can but hope that the able committee having the matter in charge will disappoint expectations founded upon such a state of things. If anything can render the banking system of the country completely odious it will be to make it a monopoly.

It is obvious that besides the reasons I have given for not withdrawing the greenback circulation, the loss of interest which would attend such a course would be a matter of serious moment. The $27,000,000 interest money saved annually by the circulation of Government notes must, in case of their withdrawal, be added to our taxation, and the labor of the country be made to pay so much more for the benefit of the stockholders of the banks whose notes would take the place of those withdrawn. I say labor, for shift the burden as we will, the larger end of national taxation will always be borne by labor. This is a very considerable sum, and if it can be saved year by year it is our duty to do it. When we shall have resumed specie payments, the burden of raising even $300,000,000 a year will be found quite sufficient for the comfort of tax-payers.

For these reasons I prefer to save the Government paper at the expense of the circulation of the banks. I have heretofore urged that Government should take to itself the paper circulation of the country. Let it do so now. Tax the bank circulation. That belongs to but few. Preserve the notes of the Government, because they belong to all.

But further. This bill proposes to take money now subject to taxation and place it without the reach of State or municipal assessment. Now it is subject of taxation everywhere. I do not suppose it is generally taxed, but it probably does not altogether escape the assessor, while a very considerable fraction of it is found in the deposits of the banks which are subject to national taxation. We have already issued over eleven hundred millions of gold bonds, which, by the law authorizing them, are specially exempt from State and municipal taxation. In other words, the present funded debt of the country is entirely exempt from State assessment. We cannot now have it otherwise if we would. It is part of the contract, and the faith of the nation must be observed.

But what shall be done in the future ? Shall we extend the same favor to the holders of the remainder of our debt ? It is a grave question. At present nearly $2,000,000,000 of the public debt are exempt from taxation. The items consist of---

Gold-bearing bonds ...... $1,177,867,291

Treasury notes called seven-thirties .... 818,000,000

Total ......... $1,995,867,291

The remainder of the public debt, over $700,000,000, is either now subject to municipal taxation or may be made so by Congress without breach of public faith.

This bill proposes to permit the Secretary to fund these $700,000,000 on the same condition as the present funded debt, and that is, entire exemption from municipal taxation. The country tolerated the non-taxation of bonds issued during the war on the plea of necessity. We were engaged in a struggle of which the issue was felt by many to be doubtful. Capital is proverbially timid. It feared loss, and in order to obtain its assistance the provision was inserted that all the extraordinary taxation which would be necessitated by the war should seek other objects, and in no case should its burdens fall upon the bonds of the United States. It was a hard bargain. I thought it unnecessarily hard, and voted accordingly. But it was made and must be kept. But what excuse have we now for renewing it ? It may be said that our bonds cannot be placed on its good terms without this exemption. Very true. But let us suffer the discount. Better do that than place the Government in the position of doing an injustice.

It is matter of no small moment. The people of the country are much more oppressed by local than by national taxation. In many parts of the country taxation on land amounts to large rent. In my State the State taxation last year for State purposes was one and a half per cent. of a fair valuation. In addition to this was the county and town taxation, and the three put together could hardly have amounted to less than four per cent. on the average; and this on a full valuation.

Mr. Hayes, one of the revenue commissioners appointed by the Secretary under authority of Congress, says of this taxation, after full examination of the subject:

"The additional local taxes which are levied everywhere are for State, country, or township, road, and school purposes. These, with special war taxes, to pay for moneys expended in recruiting and bounties to soldiers, are as high as five per cent. in it a number of counties; leaving the special taxes out of view, they will probably average nearly one per cent. We have seen that in New York they are ninety-nine and a half of one per cent. If they were only sixty-six and two thirds of one per cent., the average of all taxes under State authority, including municipal, would be just one per cent., and that figure may be taken as a fair equation of all the taxes by or under State authority. At that estimate the local revenues would be $150,000,000.

"The only tax paid for any purpose by those whose property is all in the Government securities, except the tax paid on articles of consumption, which is nearly as large, and a thousand times more onerous on the laborer than on the millionaire, is the tax on incomes. This tax is more easily evaded by the bondholder than by any one else. When the local assessor calls he can show his bonds, and the business of the assessor is at an end with him. When the assessor of the General Government calls, his bonds may be held on foreign account — at all events, he alone knows the amount. Whether honest or dishonest, he has no tax to pay if he hold but $10,000 in gold six per cents. His neighbors are taxed to pay bounties for the substitutes for his sons when the country claimed their services in the field. They are taxed to pave and light the streets and adorn the parks in which he takes the air, to afford school for his children, to provide courts and juries and policemen for the protection of his person and to preserve from the robber or the burglar the very bonds in question. From all those reasonable taxes he is exempt.

"The fact of this exemption with no equivalent taxation is known, and is causing irritation all over the land. It is felt as a hard and unjust discrimination against those who have tied themselves to the country by becoming owners of the soil, and who are using their means in adding to the wealth of the nation by fair and honest industry."

Mr. Hayes proposes a general taxation of bonds by the Government as a substitute for local taxation. He suggests one per cent. to be deducted when coupons are paid. He gives the statements of some of the wealthiest men in New York who acquiesce in the propriety of his views. But I confess the plan does not strike me favorably. It is simply scaling down the interest. When the English Government cut down the interest of its debt, they accompanied it with an offer to pay the principal. We could fairly do no less.

I prefer to see the experiment tried of issuing bonds which shall take the same chance as other property of like value. Let them be sold at their market value, and taxed fairly. I do not believe the serious results apprehended would follow.

State bonds are taxable, and still they rule on the average as high as national bonds; and in many cases higher. Why is this ? If it be because there is after all a feeling of distrust in the public mind and apprehension that the nation may grow weary and throw off its burdens; if this feeling of distrust permeates the financial mind and makes it falter when it puts up its money for the national securities, may it not be removed, partially at least, by removing one of the great causes of public uneasiness ?

It has been easy to exhibit the strength of the security of the public debt by statistics; abundance of property, great income and increasing, as the daily returns attest; resources available and sufficient to pay principal and interest within the lifetime of many of this generation. And still United States sixes are selling in London at 70, while British consols bearing three per cent. interest bring 87.

Our national debt has been attacked North and South. In the North the only salient point of attack has been its non-taxable qualities. The South, of course, objects to it because it was the great engine for their subjection. The northern objection we can obviate. The southern we must continue to conquer. Thus, it may be that, after a little, the taxation which stocks will undergo if my amendment is adopted, may enhance their market value.

In furtherance of this view it must be recollected that the price of our stocks here is much influenced if not absolutely controlled by the price they bring abroad. Nearly one third of our funded debt is owned in Europe. Of course it makes no difference in the London market whether the bond sold there would or would not be taxed in New York if held there at the time of the annual assessment. The price there is governed by the views they take of the general posture of affairs here, and they follow considerations entirely outside of questions of taxation. And for one I see no reason why the Secretary should not be allowed to sell bonds abroad if he can get a better price for them than at home. Bonds will of course go abroad if the market price calls them there. And if holders can without expense of brokerage receive their dividends in some convenient place in Europe our bonds would undoubtedly appreciate, and as they enhance in value the price of gold on this side declines, and we approach specie payments. Any one who has interested himself in such matters for the last six months cannot but have noticed that gold declines in New York with the advance of bonds in London, and advances when they decline there. Thus, the sale of bonds abroad, at enhanced prices, will help us on the road toward specie.

With these views I cannot vote for the bill before the House. I doubt the necessity of enforced contraction of the currency. But if it is to be contracted by law let the bank circulation go first. Tax that out of existence, if necessary. I will go as far as the man who will go farthest in this direction. When that has been done retire so many "greenbacks" as may be necessary. Once on a specie basis let the business of the country regulate itself. Doubtless many of us will live to see the day when, in the abundance of gold, we shall have a currency more nearly metallic than ever before. But so long as we use paper let it be the best possible, and that is certainly the "greenback."

Mr. PRICE. I ask the gentleman to yield to me.

Mr. PIKE. I yield to the gentleman the remaining portion of my hour.

Mr. Price. I yield to the gentleman from Ohio for a moment.

Reorganization of the Army.

Mr. SCHENCK. Mr. Speaker, the Committee on Military Affairs reported to the House some days ago House bill No. 361 to reorganize and establish the Army of the United States. There are a great many applications for copies of that bill, but the first print of it is entirely exhausted. The committee have to some small extent revised the bill, making some verbal amendments and adding some sections. I ask leave to report back the bill in its present shape as a substitute for the other, and move that it be recommitted and ordered to be printed.

There was no objection, and it was ordered accordingly.

Mr. Spalding. Has not the Army bill passed the Senate ?

Mr. Schenck. One Army bill has.

Mr. Spalding. Had you not better also include a motion to print that bill ?

Mr. SCHENCK. I will ask that that be printed after awhile.

I now move that five hundred extra copies of the House bill be printed for the use of the members of the House.

The motion to print extra copies, under the law, was referred to the Committee on Printing.

Mr. SCHENCK. I now move to take from the Speaker's table, Senate bill No. 734, to increase and fix the military peace establishment of the United States, and that it be referred to the Committee on Military Affairs, and ordered to be printed.

The motion was agreed to.

LOAN BILL — AGAIN.

Mr. PRICE. Mr. Speaker, when we come to a vote upon the bill now under consideration and I shall be required, with other members of the House, to say ay or no to its passage, my convictions of duty will require me to vote against it.

I shall do this reluctantly, because in so doing I shall differ from the chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means, in whose judgment I have much confidence, and whose fidelity to the best interest of the country no man doubts, and I suppose I shall also differ from the Secretary of the Treasury, to whose judgment in financial matters I have been accustomed to defer. But, sir, this bill presents to my mind such plain and palpable objections that I feel certain it cannot be for the interest of the country to pass it.

The same general rules which apply to the management of the financial affairs of an individual will hold good when applied to that of the nation — there is no difference in kind, they differ only in degree. When a prudent business man finds himself from necessity, or any other cause, financially embarrassed, he goes to work with energy and system to ascertain, not only the nature, extent, and amount of his indebtedness, but also his present and prospective ability to meet the same. If in that investigation he finds that there is no probability of any increase of the amount of claims against him, and that his receipts are in excess of his proper and legitimate expenses, there is but one other matter of importance for him to attend to, and that is to secure such an extension of time as will enable him to use this excess of receipts in liquidation of the claims against him. And I risk nothing in asserting that any man thus financially circumstanced would be considered as perfectly safe, and would need no enactments of any legislative body to relieve him from embarrassment.

This is a very plain proposition, so plain, indeed, that the most moderate intellect can comprehend it perfectly. And if I may be allowed, Mr. Speaker, I will say in this connection that the mystery which is supposed by many to surround, and to a certain extent to enshroud, what is commonly called great financial ability, skill, &c., is simply, in my opinion, great nonsense, a very great humbug. I am not referring now, sir, to such financiering as was practiced by Ketchum and men of that class. That kind, I am willing to admit, requires, in order to insure success, very extraordinary and very peculiar ability. But the kind of financiering of which I speak, and which the nation requires at this time, is simply an exercise of common care and common honesty, led and governed by common sense.

The bill before us is of course intended to relieve the nation of some real or supposed financial embarrassment, and for that purpose clothes the Secretary with extraordinary powers.

The first question which presents itself for our decision is this: is there any necessity for it ? We know the nation is in debt; we have borrowed money to preserve our national existence. But are our creditors pressing us ? Can we or can we not have such an extension of time as will enable us, by a judicious use of the means at our command, to meet all the claims against us ? If our creditors are clamorous, and we cannot have an extension of time, then we must resort to all the means within our reach, ordinary and extraordinary, and make any and all sacrifices necessary to preserve our national faith and national honor, just as an individual under similar circumstances should do.

How do the figures stand upon our balancesheet ? And how do our assets and liabilities compare ? I know of no other way to get at the truth on this subject; and though there may not be much oratory in a column of figures, there is considerable eloquence, particularly when we find a handsome balance on the credit side of our ledger account.

At the commencement of this session I made up from the reports of the different heads of Departments a statement of the financial condition of the country, and on referring to it now I find the following state of facts existed then, and are substantially the same now. Our indebtedness is as follows, to wit:

$1,164,011,652 bonds at 6 per cent., making in interest ... $69,840,699.00

$830,000,000 bonds at 7.3-10 per cent., making in interest ........... 60,590,000.00

$205,307,000 bonds at 5 per cent., making in interest ..... 10,265,350.00

$155,012,745 bonds at 5½ per cent., making in interest ..... 8,525,700.00

Total of interest for the year ..... 139,221,749.00

Then we have in addition to this, estimated expenses for the year, as follows:

For the Army .... $33,814,461.83

For the Navy ........ 51,000 000.00

For civil expenses ..... 42,000,000.00

For pensions ..... 10,000,000.00

136,814,461.83

Which, added to the amount of interest falling due annually upon all kinds of our national debt, gives us a sum total of ...... $286,036,210.83

If we have this amount of money we shall be able to pay cash for all purchases necessary to be made, and meet every obligation as it falls due. I may state, in this connection, that we have about $450,000,000 of indebtedness in the shape of legal-tender notes; but these bear no interest, and are payable at no fixed time.

Having thus ascertained our liabilities, we have one side of the account; and now the next question which presses for an answer is, what are our resources ? How can we pay ? I find, on referring again to my compilation of figures, the estimated receipts for the year from internal revenue, tariff, and all other sources, to be $472,000,000, leaving a clear balance in the Treasury at the end of the fiscal year of $185,963,789.17.

But it may be said that these receipts are only estimated, and therefore may not be correct. I grant this, but I find that in the three months which have transpired since these figures were made the actual receipts have exceeded the estimates to such an extent as to justify the honorable gentleman from Massachusetts, [Mr. Hooper] who is on the Committee of Ways and Means, in placing the receipts at $500,000,000 instead of $472,000,000, which would leave us a balance in the Treasury at the end of the year of over $200,000,000.

Now, Mr. Speaker, when we take these facts and figures, in connection with the other important fact that we may safely and certainly calculate on a decrease of these expenses and an increase of our income from increased population and a continuance of the development of the resources of the country, I ask what there is to frighten us from the ground of safety which we now occupy. If it is asked how we are to reduce our expenses, I reply by referring to one item in the figures from which this calculation is made. It will be observed that the estimate for the Navy is placed at $51,000,000, while the actual amount named in the bill passed for that purpose a few days since fell below half that amount.

Notwithstanding, then, the immense strain to which the nation has been subjected in the last four years in her finances, we find that upon posting the books and taking an account of stock we are in a sound and healthy condition.

Our surplus will enable us safely to repeal some of the petty and annoying features of the income tax law, so as not to compel farmers and mechanics to give an account of every pound of butter and dozen of eggs sold, and of every dollar's worth of every article manufactured.

A very small, almost insignificant part of our debt is payable on demand, and the balance runs from fifteen to forty years, at the expiration of which time we shall, if republican ideas and principles prevail, be the richest and most powerful nation on the globe. The feature of this bill, which provides that the $450,000,000 of legal-tender notes, which bear no interest, and which are redeemable at no definite time, may be funded in six per cent. gold-bearing bonds, is to me so strange and unaccountable that I am astonished to find it presented to the House for consideration. This feature of the bill, if adopted, would involve an additional annual expenditure of $27,000,000 in gold, for which the people of the country must necessarily pay an additional tax. Would any prudent and sensible business man, who had given his note payable at his own option, and without interest, be likely to take up that note and give another for the same amount payable at a certain time, with interest at six per cent., payable semi-annually in gold ?

Why, sir, the bare mention of such a transaction provokes a smile of incredulity, and yet this is precisely one of the features of this bill. The Government owes $450,000,000 on which we pay no interest, and which is redeemable whenever it suits the convenience of the Government; and yet if this bill becomes a law this $450,000,000 may be funded in bonds bearing six per cent. in gold.

It may be said, sir, that these legal-tender notes are depreciated, and therefore ought to be retired. A sufficient answer to this is found in the fact that legal-tender notes are to-day about as good as six per cent. bonds, and would, in my opinion, be much better if the bonded indebtedness of the Government was increased by the addition of this $450,000,000.

Mr. Scofield. I desire to ask the gentleman a question.

The SPEAKER. The hour of the gentleman from Maine [Mr. Pike] has expired.

Mr. ALLISON obtained the floor.

Mr. ASHLEY, of Ohio. I move the gentleman from Iowa be allowed to conclude his remarks.

Mr. Smith. I object.

Mr. ALLISON. I will yield to my colleague a portion of my time.

Mr. Scofield. Now, let me ask my question. Are not the notes proposed to be funded already due ? If you look upon the face of these notes you will observe they are payable on demand at the sub-Treasury at New York; and if you go there, as I did, they look to see whether you are a fool or a crazy man, in expecting that the United States is going to comply with that printed promise.

Mr. PRICE. Mr. Speaker, the gentleman from Pennsylvania is too good a lawyer not to know that it requires occasionally, at long intervals, an exception to prove the rule. He has given the exception; it proves the rule that there are few men who ask that these notes be redeemed, for the reason that legal-tender notes are admitted on all hands to be as good paper money as we can have.

Mr. Scofield. The reason they are not presented is because the people know they will not be paid while gold is at a premium.

Mr. PRICE. My friend knows they are made payable in other notes.

I should like to have time to answer all the questions which may be put to me. I have only a few minutes, and I have some figures I wish to put upon record.

I only need to refer to the price-current of New York to prove that the six per cent. gold-bearing bonds are only one per cent. above "greenbacks."

It would certainly, then, be very bad policy to fund these notes, and thus make ourselves liable to pay $27,000,000 per annum for what we are now getting, and can continue to get, honestly for nothing. In this connection, Mr. Speaker, I wish to call the attention of the House to a fact, well known to all bankers, which is, that we may safely calculate that at least five per cent. of this $450,000,000 will never come back for redemption, on account of being worn out, lost, and destroyed in various ways, thereby saving to the Government $22,500,000 in addition to $27,000,000 annum.

The six per cent. bonds of 1881, and the five-twenties and ten-forties need no change. The seven-thirties are fundable by the terms of their issue, or if not, power should be given for that purpose, leaving only the compound-interest notes to be provided for by law, which I think the Secretary of the Treasury should have power to do. My judgment in this matter, sir, is that we ought to allow as little legislative tinkering with the law regulating our financial matters as possible, studying the most rigid economy in all our expenses and applying the excess of receipts over expenditures each year to paying off and canceling an amount of indebtedness equal to such excess. By this means we shall at once be enabled to enter upon a reduction of taxes and a reduction of indebtedness, bringing the nation every month and every day, by safe and easy approaches, nearer to a permanent resumption of specie payments.

Mr. Speaker, the ideas which I have attempted to embody in these few remarks are so plain as to require no elaboration.

The great lesson, sir, which we as a nation need to learn, is more dependence upon ourselves and less upon other nations. Self-reliance is the great secret of success, in nations as well as individuals. When we shall have learned to appropriate the proceeds of our own labor, we shall be richer and more independent than ever before. When we shall have brought the spindle and the loom closer to the consumer of manufactured articles, we shall have done much for the toiling millions. When we shall have freed ourselves from the absurd idea and practice of sending our cotton three thousand miles to find a spindle and a loom, with a hope that we may be able to send a barrel of flour after it to feed the spinner and the weaver, and in the operation taxing the labor which produced both the cotton and the wheat to pay freights and charges; I say, sir, when we shall have abandoned these absurd practices we will have lifted a burden from the shoulders of hard-handed labor which cannot be done in any other way.

A speedy return to specie payments is what every true friend of the Government must work for; but the idea of immediate resumption is Utopian in the extreme. No sane man standing upon the top of Bunker Hill monument would think of descending by a leap to the ground, but would choose the more rational and prudent course of coming down step by step.

In the opinion of some men all of our financial ills are to be cured by immediate resumption of specie payments, and all our political evils by an immediate admission of the States recently in rebellion. No man, Mr. Speaker, desires more earnestly and sincerely than I do the accomplishment of these objects. But my judgment compels me to believe that it is the part of wisdom to "make haste slowly" in both cases.

Let the work rather be slow and permanent than hasty and insecure.

Let both be laid upon foundations so broad and so deep that no financial or political earthquake can ever move them.

Now, sir, I will reply to the argument made yesterday by the gentleman from Illinois, [Mr. Wentworth]. I am only sorry he is not here. If there are any gentlemen here who hold the same view I will say it for their benefit. He compared the "greenbacks" of this country to the assignats of France. I wanted to ask then, and I will do so now, whether there is any parallel between the two kinds of currency; whether he does not know, as well as he knows of his own existence, that the French assignats had no foundation for their redemption compared with ours ?

When a man who claims to be an American citizen, in the Halls of Congress or anywhere else, undertakes to compare the currency of this country, which is as good as was ever issued by any bank of the United States, with the rotten system of assignats in France, I assert that he is lacking in one of two things, namely, either a want of proper information on the subject or a want of a disposition to do justice to the currency of the country. And these, sir, are as mild terms as I can possibly use in reference to it.

Mr. Garfield. [James Abram Garfield (1831–1881) (R) Ohio] I would ask the gentleman, when he speaks of the assignats of France, whether he is aware that they were founded on the most reliable property in the realm, namely, real estate that was believed by everybody to be worth fully the sum of £80,000,000 sterling.

Mr. PRICE. I said as compared with ours that was a rotten basis. And the gentleman from Ohio [Mr. Garfield] is too well versed in the history of that matter not to know that what he calls the security of £80,000,000 based upon the most reliable resources of the country was confiscated property of the church. Is that, sir, to be compared with the security upon which our legal tenders is based — the hard-handed labor, the integrity, the wealth, and the resources of this whole Republic, where every man, woman, and child is bound for the payment of the debt to the extent of their last dollar and last day's labor, and to which may be added our vast agricultural and mineral resources ? And will the gentleman from Ohio [Mr. Garfield] stand here and make such a comparison as that to go forth to the world ?

Sir, I had hoped that the day had gone by when a gentleman would stand up before the American people and make such a comparison. The reason why the system of assignats was rotten was because the foundation for their redemption was insufficient and insecure. But will any man on this floor dare to say that the foundation of the security for our legal tenders and Treasury notes is insecure and insufficient ? No man with an American heart, in his bosom dare make use of any such language in this Hall. No one will say it unless he belongs to that class who during the last four years of the nation's trial has by unfair means and unjust comparisons tried to depreciate our currency and thus embarrass our operations.

Mr. Hooper, of Massachusetts. I want to ask the gentleman a question. He says that when a man is in such a financial condition that he cannot meet his payments he asks for an extension of time, and that the Government is now precisely in that position — that it wants an extension of time. Now, I desire to know what there is in this bill beyond that — a mere extension of time. It does not authorize any increase of debt. It does not authorize money to be borrowed. It merely authorizes the bonds, at long time, to be issued in place of those that are immediately or soon to be redeemed.

Mr. PRICE. In the first place, I did not say we wanted an extension of time. I said that if a man was in that condition he would ask for an extension of time. But to answer that in a sentence, I have only to say that the gentleman from Massachusetts [Mr. Hooper] himself told me yesterday that the receipts of this Government were every day more than its expenditures, and a man in that condition does not want an extension of time. A man who is receiving more than he pays out is in a sound and healthy financial condition. When this Government comes to the condition that it has a debt to pay without any means upon which to draw to pay it, then I will admit that we must have an extension of time. But the country is not in that condition, and I want that living fact to go to the country. We are in a sound and healthy financial condition, with an income exceeding our expenses and a credit never before equaled by any nation on the globe when just emerging from a gigantic and wasting war.

Mr. Allison. Mr. Speaker, I do not propose to occupy the time of the House long in the discussion of this measure. It seems to me that thus far the arguments against this bill have been, in the main, arguments in favor of or against the particular policy that should be pursued by the Secretary of the Treasury in its administration. Now, unfortunately for us, we cannot all be Secretaries of the Treasury. It is for us to make the law and to give the Secretary of the Treasury the power to administer it in accordance with the discretion placed in his hands; and the only question, it seems to me, that is proper for discussion is what discretion should be conferred upon the Secretary of the Treasury.

Now, sir, we all agree that it would be well to reduce the price of gold. We all agree that sooner or later this great nation of ours must come back to specie payment; that sooner or later, as a nation and as individuals, we must pay our debts in coin that is current all over the world. Therefore the only question that seems to have attracted the attention of gentlemen here is, when shall that time come ? Shall it be to-day, to-morrow, or two or five years hence ?

Now, I assert that it is a question that must devolve upon the Secretary of the Treasury, controlled and directed by the inevitable laws of trade and finance that cannot be controlled one way or the other by legislation.

Now, what does this bill propose ? Is it a proposition to come back to specie payments at a particular period of time, or to postpone specie payment until a particular period of time ? It is neither. I maintain, that there are but two things authorized in this bill which the Secretary cannot do now under the authority of the several acts of Congress. The one is that he is enabled directly to sell the bonds of the United States upon such terms as is within his own discretion for United States notes or legal-tender Currency; and the other is that he may sell those bonds for a sum less than par. That gives him a discretion which he has not now directly, but which he has indirectly under the existing law.

Gentlemen seem to be very much exercised lest the Secretary of the Treasury should withdraw the "greenback" circulation of the country. I assert here that under the existing law the Secretary of the Treasury has the power to withdraw from circulation every dollar of the greenback circulation in existence. He has that power already by existing law. By the act of June 30, 1864, the Secretary is authorized to convert Treasury notes and United States notes into the kind of bonds authorized by that law, to wit, bonds payable not less than five years nor more than forty years — five-twenties or ten-forties. He has the power to convert that class of securities into long bonds, by first converting them into either seven-thirty Treasury notes or compound-interest notes; he can do either. And then, by the act of March 3, 1865, which is supplementary to that act, he can convert those seven-thirty notes and those compound-interest notes into bonds, either five-twenties or ten-forties, at his discretion; so that every dollar of the greenback circulation of the country can be converted, sooner or later, into long bonds without any additional legislation.

---[And Lincoln signed that law during the war, why would he not have signed it after the war ?]

Now, sir, the proposition of the committee is that the Secretary of the Treasury shall be authorized to do directly that which he can now do indirectly under the act of June 30, 1864, and under the act of March 3, 1865; because, under the latter act, he can convert, with the consent of the holders, any species of indebtedness existing under any act of Congress into gold-interest-bearing bonds. Under the act of June 30, 1864, he can convert United States notes into Treasury notes bearing interest, and can convert any interest-bearing notes into long bonds, at his discretion.

Now, a majority of the committee think that it is desirable to give the Secretary of the Treasury directly that authority which he has indirectly, to so convert this indebtedness into long bonds. My friend and colleague [Mr. PRICE] says that if we have a debt maturing we should pay it with our current receipts. That would be all very well if we had the power to do it; but we must remember that within the next three years there will be due nearly twelve hundred million dollars of this indebtedness. Now, that indebtedness must be provided for within two years and eight months, I believe. A prudent man would not wait until his debts matured before providing for their payment, if possible. He will by some means endeavor to secure the necessary means to meet those obligations before they mature.

Mr. Wilson, of Iowa. I would ask my Colleague [Mr. Allison] whether the Secretary of the Treasury has not been engaged already in funding seven-thirty notes in gold-bearing bonds under existing law ?

Mr. ALLISON. Undoubtedly; by the last monthly statement I see that he has funded $12,000,000 of seven-thirty notes into long bonds, five-twenties I presume; at least it is so stated in the newspapers. Of course he has had power to convert seven-thirty interest-bearing Treasury notes into long bonds, provided, however, that the consents of the holder is always obtained to that conversion. In other words, if I hold a seven-thirty interest-bearing note, I can go to the Secretary of the Treasury and convert it into five-twenty bond, but if I do not desire that conversion, the Secretary of the Treasury has not the power to sell five-twenty bonds in order to procure money to pay me for the seven-thirty bond which I hold.

Mr. Wilson, of Iowa. I would also ask my colleague whether the Secretary of the Treasury cannot under existing law sell his five-twenty bond for compound-interest notes, and then reissue compound-interest notes for the purpose of paying off the seven-thirty interest-bearing notes ?

Mr. Allison. The Secretary of the Treasury, as a matter of course, can receive compound-interest notes in payment of long bonds, and under the existing law he can re-issue compound-interest notes. But that may not be desirable; it may be desirable that he should have some power conferred upon him by which he can sell his long bonds directly for greenback currency with which to pay off seven-thirty and compound-interest-bearing notes, both of which I believe it desirable to pay off at the earliest possible moment.

Now, sir, the compound-interest notes and the temporary loan which my colleague [Mr. Price] says will cost us nothing, I regard as the most obnoxious loan now in existence; I regard that loan as the most expensive loan which we now have; and for the reason that it now amounts to $119,000,000, and the Secretary of the Treasury is compelled to keep in his vaults a large amount of money for its redemption. He has to-day in the Treasury of the United States the sum of $23,000,000, and perhaps more, of greenbacks, for the express purpose of paying this temporary loan as it may be presented. And besides, the way in which this temporary loan is managed, is, I think, obnoxious and injurious to the public interest. How is it managed ? By giving the New York association of banks $25,000,000, the Boston association of banks $10,000,000, and the Philadelphia association of banks $5,000,000 or $10,000,000 more, which sums are payable upon the presentation of the certificates. The Secretary of the Treasury is therefore compelled to keep constantly on hand a large amount of greenbacks in order to pay this temporary loan whenever presented. And he will always be compelled to pay that temporary loan at the very time when it ought not to be paid; that is, when there is a scarcity of currency in the country. Thus, he is paying a large interest for a loan that is of little practical value to the Treasury.

Now, sir, as I have said, I know of no power that is directly given by this bill, except the power to sell those bonds at less than par should such a necessity arise. For one, I am not in favor of permitting the evidences of the indebtedness of the United States to be sold for less than par. I believe that since the beginning of this war we have not at any time sold our evidences of indebtedness for less than par in notes of the United States. But it may be for the accommodation of the bankers and brokers, who seem to me to be the terror of my friend from Illinois, [Mr. Wentworth] that those bonds should be reduced a little below par. If that should be done, will any one say that the wheels of this Government would be stopped, because for a time we were compelled to sell United States bonds for less than par ? Sir, the inevitable interests of the banks and capitalists of this country holding these securities, will have a tendency to keep them at par. The national banks alone hold $500,000,000 of them. Now, the very moment the Secretary of the Treasury issues any of his bonds at less than par, that moment the other bonds of the United States will be reduced to the price for which he sells his. Therefore it is that I believe the inevitable laws of trade and finance will keep these bonds at par.

One single remark further in reference to this greenback circulation. The Secretary of the Treasury does not, in his annual report, propose an immediate return to specie payments. I believe that the state of the country is now much more satisfactory than he believed it to be when that report was written, because at that time prices were ruling high, and gold was at a premium of forty-seven per cent., while the premium is now but thirty per cent. — a reduction of seventeen per cent. But the Secretary of the Treasury, in his report, states that the reduction of the greenbacks or United States notes by $100,000,000 will probably secure what we all desire, the resumption of specie payments.

Now, sir, my friend from Illinois, [Mr. Wentworth] my colleague upon the Committee of Ways and Means, has great anxiety with reference to a class of men in this country, who, he apprehends, are seeking to destroy the public credit. I have no such fears. I believe that the interests of the moneyed men of this country are all upon the side of keeping our securities at par. And I believe that it is to our interest as a people, as a nation, to keep as many of these securities as possible within our own country, so that the interest and the principal may finally be distributed among our own citizens. Therefore it is that I am desirous that the clause with reference to the dispositions of these bonds abroad shall be stricken out.

It is true that the Secretary of the Treasury may under existing law and by this bill, if he believes that it will be good policy, negotiate a loan abroad. He may negotiate a loan outside of the United States; but the interest and principal must be payable in the United States. I can see but very little difference, whether the Secretary of the Treasury authorizes an agent to sell these bonds abroad, or whether he permits New York bankers and foreign agents to purchase them and send them abroad.

But this bill limits the power of the Secretary to increase the national debt under existing law; he can if he chooses increase the public debt to a large amount, and the people are anxious to know where that limit shall be; and this bill proposes that there shall be no further increase, which is an important limitation upon existing power vested in him.

Mr. Speaker, I yield the remainder of my time to my colleague on the committee, the gentleman from New York, [Mr. Conkling].

Mr. Conkling. I yield to the gentleman from Massachusetts, [Mr. Boutwell]