"The nation's commercial banks can be divided into three types according to which governmental body charters them and whether or not they are members of the Federal Reserve System. Those chartered by the federal government (through the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in the Department of the Treasury) are national banks; by law, they are members of the Federal Reserve System. Banks chartered by the states are divided into those that are members of the Federal Reserve System (state member banks) and those that are not (state non-member banks). State banks are not required to join the Federal Reserve System, but they may elect to become members if they meet the standards set by the Board of Governors."As of March 2004, of the nation's approximately 7,700 commercial banks approximately 2,900 were members of the Federal Reserve System --approximately 2,000 national banks and 900 state banks."

"We currently have 121 state member banks in the 8th District [St Louis]. Those are the banks that we supervise. However, every national bank is also a Fed member institution. There are 98 national banks in our District. Those banks are supervised by the Comptroller of the Currency. I suspect that the question relates to state member banks, not all member banks.

"Each state member bank must hold Federal Reserve Bank stock in an amount equal to 3% of that bank's capital stock and surplus accounts. So if a bank has $1 million in capital stock and surplus, it must hold $30 thousand in Federal Reserve Bank stock. Each share of Fed stock has par value of $100. So holding $30 thousand in Fed stock would equate to 300 shares. Fed stock records are maintained by our Accounting Department, but I doubt that the Department would provide information on banks' holdings of Fed stock. However, with information regarding a bank's capital accounts being publicly available, calculating how many shares of Fed stock are held is a pretty simple exercise."

---From: "Jane M. Davis" <Jane.M.Davis@stls.frb.org>

Hearings before the Committee on Banking and Currency, United States Senate, 63rd Congress, 1st Session, on House Resolution 7837 (Senate bill 2639) a bill to provide for the establishment of Federal Reserve banks, for furnishing an elastic currency, affording means of rediscounting commercial paper, and to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes.

Committee on Banking and Currency: Robert L. Owen, chairman ... Oklahoma. James A. O'Gorman .......... New York. James A. Reed .............. Missouri. Atlee Pomerene ................. Ohio. John F. Shafroth ........... Colorado. Henry F. Hollis ....... New Hampshire.

Gilbert M. Hitchcock ....... Nebraska. Knute Nelson .............. Minnesota. Joseph L. Bristow ............ Kansas. Coe I. Crawford ........ South Dakota. George P. McLean ........ Connecticut. John W. Weeks ......... Massachusetts.

Statement of Hon. William Harvey Berry, (1852-1928) of Chester, Pennsylvania.

Senator Shafroth. Mr. Berry is the gentleman whose book [Our economic troubles and the way out; an answer to socialism and a discussion of the Aldrich bill, published in 1912] we started to read in the committee and of which we read several chapters. I wish it also to appear in the record that Mr. Berry was at one time treasurer of the State of Pennsylvania.

Senator Pomerene. And he is now collector of customs.

Mr. Berry. There are two general schools of thought on this currency question, one of which supposes that it is necessary that a certain restraint be put upon the activities of the people. I think that school would perhaps be most ably represented by the professor who has just preceded me and to whose remarks I have listened with so much interest.

---[ "My name is O.M.W. Sprague, and I am converse professor of banking and finance in Harvard university. I indicated the defects in our banking system which this bill is designed to remedy. I believe that the measure, if adopted in its present form without change, would provide the machinery which under competent management would very largely remove these defects. The institutions to be established would have adequate resources to meet seasonal requirements and to enable them to handle emergencies effectively. Their operations would also tend to make commercial paper the most liquid asset for all banks; this because the Federal reserve banks are limited in their rediscounting operations to commercial paper."

]

The other school of thought is that in which the concept of individual freedom in the matter of activity is the great consideration. I am of the second class. I do not believe that any restraint should be put upon the activity of any man. I do not believe that it is wise to put any restraint upon any individual who wishes to exercise his activity in the production of wealth; nor do I believe that any man should sit in judgment as to what activity he should engage in.

Therefore I approach this subject from a different standpoint altogether from that which the professor has presented. I am sorry to break in upon your deliberations because it will be a rather abrupt change in the viewpoint at least.

I am not a banker. I am like the fellow who when he was asked whether he was the mate of the vessel or not said, "No; I ate the mate."

I am the fellow who stands on the outside of the bank, and I speak from the standpoint of the business man who uses the banks.

The Senate Committee on Banking and Currency sent out a list of questions, which in my judgment were very searching and covered the entire field of thought under consideration. I spent a good deal of time in endeavoring to intelligently answer those questions. There were 33 questions, but they are not all quite pertinent to this discussion this afternoon. I shall not trouble you with any of the details in regard to the organization of the bank and I have no suggestions to make along that line.

Senator Shafroth. Mr. Berry, I read those answers, and I feel that they ought to go into the record right here. They are splendid answers to those questions.

Mr. Berry. I am perfectly willing to put them into the record, but I thought it would be rather an abuse of your time to undertake to read them all now. There are a few which it will be necessary for me to refer to as I make my argument on this bill in order that they may be properly understood.

The Chairman. I think it would be well to have the questions of the committee and the answers prepared by Mr. Berry incorporated in the record.

Mr. Berry. I want to make this preliminary statement. I believe, with the President [Woodrow Wilson], that every man who has an asset to hypothecate ought to be able to secure credit in a competitive market, in a market which would establish a just interest rate, and it is with that point in view that I have prepared the figures I have here to submit to this committee.

---[Mr. Berry is describing Nicholas Biddle's idea:--- turn all assets into credit, and all credit into currency (in this case into credit-page entry) The real aim should be not the facilitation, regulation and adjustment of the credit system which carries in itself its inherent flaw, and results inevitably in bubble and burst, but the promotion and facilitation of cash transactions, cash reserves, out of debt. (capital-ism == conduct business on the basis of accumulated capital; not conduct business on the basis of credit.....) ]I believe that to be the great desideratum.

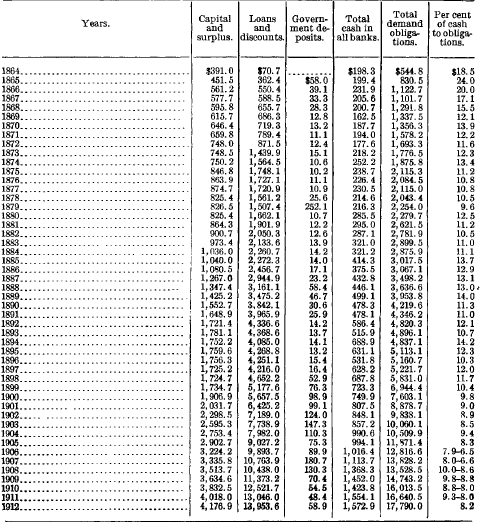

Now, it will save time for everybody concerned if I go over some of these answers and refer to portions of them respecting matter which I think very pertinent. In the first place, I would like as many of you gentlemen as can to make use of this table. It is a table compiled from the report of the Comptroller of Currency and appears in my books.

Senator Shafroth. That shows that only 8 per cent of the money of the country is used.

Mr. Berry. My remarks will be largely a statement of facts. The first question asked by the committee was:

What are the essential defects of our banking and currency system ?

My answer to that is: The basic defect of the system is in the inability of the banks, collectively, to secure legal tender money in sufficient quantities to enable them to safely meet the legitimate demands for credit.

---[during the war, with an enormous government demand for goods and the resulting overheated economy, banks were able to meet the demand (legitimate or otherwise) for credit, why not now ? is demand for credit larger today than during war ? why ?By "legitimate demands" I mean such as are accompanied by the offering of adequate security.

Any such demand for credit would incite an active competition among the banks for the privilege of supplying it, if they could safely do so; in which case an equitable interest or discount rate would be automatically established, and discrimination in favor of certain borrowers would be reduced to the minimum or entirely eliminated.

Under natural laws, as well as existing statutes, the power of the banks to extend credit is limited by the amount of reserve money that they hold. They can not discount paper beyond this point.

The Chairman. There is not the slightest doubt about that.

Mr. Berry. I will continue. Banking is founded and operated upon the law of averages determined by experience. Of the checks drawn by an individual against his account, only a small percentage will demand cash payment; the rest will be deposited, and a transfer of credit on the books will take care of them; but those who ask for the money must receive it. So that while the exact amount of money necessary to promptly meet this demand in any given case may be debatable, the fact that the bank imperatively needs some money in order to discount paper and physically care for the checks drawn against an account is beyond question.

Safe banking requires a liberal percentage above the amount ordinarily found necessary to pay checks.

In addition to this physical limitation, and because of it, the statutes require the national banks to hold an average of about 12.5 per cent of legal tender against deposits; but by means of deposits of legal tender in these banks by the State banks, trust companies, etc., the general average in the banks collectively may be, and is, considerably reduced.

A point is, and must be finally reached, however, when no further reduction in the per cent of reserve can be safely or legally made, and when this point is reached no further credit can be floated, no matter what security is offered.

In such case the transfer of cash from one bank or one city or even from one country to another can not help the general situation, since it does not increase the total held, and therefore the absolute solvency of our banks, as proven by their four billions of unimpaired capital and surplus, which is held in the form of so-called quick assets (stocks and bonds), is of no use whatever in the premises.

In such case there is nothing the banks can do but refuse to extend credit. If credit is refused, panic conditions are set up which compel the banks to withdraw existing credit. Inevitably extensions will be refused to and withdrawals made from those in whom the bankers are not personally interested, and all the evils of a so-called money or credit trust or monopoly at once appear.

Therefore the demand for credit can not be met.

A careful study of the following table, taken from the report of the Comptroller of the Currency, June 30, 1912, will show that 10 per cent of reserve money held against deposits approaches the danger line and is certainly the limit of safety. The table in my answer shows the condition of 25,193 banks of all kinds, compiled from the report of the Comptroller of Currency, June 30, 1912 (pp. 39 and 40).

It is not an exact transcription. Two or three of the columns have been brought together so as to condense it. All of the obligations are in one column and all the cash assets are in another column, so that the basis of percentage can be had. The table is as follows:

It appears from the table that in 1865 the reserve cash held was 24 per cent of deposits; and through the substitution of bonds for United States notes, and an accompanying expansion of credit amounting to $860,000,000, the reserve was reduced to 11.6 per cent in 1872. This forced a curtailment of credit [burst of credit bubble] that caused the panic of 1873.

---[As stated in the December 4, 1865, report of the Secretary of the Treasury, in 1864 and 1865 large portion of business transactions were conducted using cash, people were out of debt and had cash on hand to carry their businesses; people had no need for (fractional reserve based) bank credit.This curtailment raised the percentage of reserve to 13.4 per cent in 1874, from which time it steadily fell to 9.6 per cent in 1879. Credit was restrained [the credit bubble burst] and panic was only averted by the deposit of $250,000,000 of Government funds in the banks. (See table, p.563.)

In the next decade the coinage of silver under the Bland-Allison Act increased the legal tender money in banks, and for this reason an increase of $700,000,000 of new credit was accompanied by a rise in the reserve cash to 14 per cent in 1889. This result was hastened by the fact that in 1878 the balance of trade turned in our favor, and in 1877 the excess of exports over imports of merchandise was $150,000,000, and continued at this average throughout the decade (1877 to 1887).

This favorable balance in merchandise gave rise to an importation of gold during this period amounting to $21,654,000 per year, or a total of over $216,000,000, which, added to the $240,000,000 of silver coined in that period, made a total increase of legal tender or reserve money in the country, above the current coinage of gold, or $456,000,000 in the decade. This accounts fully for the rise in per cent of reserve during this period of business activity and credit expansion.

---[and what sort of problem did the removal of gold generate in the countries from which this gold was removed ? Presently you tell us what sort of problem the outflow of gold generated in this country a few years from now when gold decided to leave]In 1888 the balance of trade turned against us for two years, and in the period from 1888 to 1896 the average in our favor was reduced from $150,000,000 to $80,000,000.

I wish you would note carefully this statement, gentlemen. So much has been said of the cost of gold under which we labored in 1893 that this is a very important statement.

This necessitated the exportation of gold, and in this period of nine years $298,000,000 of gold went abroad, or $33,000,000 per year.

The coinage of silver ($24,000,000 per year) was not sufficient to supply this loss and provide a basis for expanding credit, and the per cent of reserve cash rapidly fell to 10.7 in 1893. There were no funds in the National Treasury from which to help the banks as in 1879 and other years. New credit was necessarily refused, and panic ensued during which $280,000,000 of existing credit was withdrawn.

---[what was needed was not reserve cash to serve as basis for a fractional reserve credit bubble, but accumulated cash in the hands of businessmen to conduct their operations]I take the position firmly and undertake to defend it against all comers that that cataclysm was due solely to the exportation of gold, due to the change in commercial relations between this and foreign countries.

---[the fractional-reserve credit-bubble of the credit system produced its usual result, right on schedule]Strange to relate, as a remedial (?) measure, the purchase of silver was stopped at this time, and the only available source of reserve money shut off in time of famine, and the country wallowed in the slough of depression until the discovery of new gold fields and new processes for refining low-grade ores in 1897 and 1898 increased the rate of gold production in the world by 50 per cent in two years, and for the simple reason that we had no money in the bank upon which we could maintain the credit necessary for our business.

---[what an argument against the goldite theological dogma that gold is money by nature, and gold alone should be the ultimate redeemer. had it not been for these discoveries of new gold we should still be in economic doldrums according to these theologians.]This gold gave immediate relief, and a period of world-wide business activity and credit expansion was inaugurated, unparalleled in history. ---[which supports my point that banks use the increase of cash to float an even larger credit bubble; and the more cash you let them have, the larger bubble they inflate, always aiming for a 20 to 1 ratio.] Reserves in our banks were strengthened, but new and undreamed-of concepts of our productive powers were awakened, and the expansion of business soon overtook the increased production of gold, and while reserves increased enormously in actual volume the percentage began to decline and in 1901 had fallen to the unprecedented low level of 9 per cent. The reduction continued until in 1906 it had fallen to 7.9 per cent, although the total reserve held had increased 47 per cent.

At this point it became impossible for the banks to physically meet the cash payments of checks or to comply with the law as to reserves, and in the midst of unparalleled optimism and business activity the crash of 1907 came.

---[and crash always comes because it is inherent nature of people who organize money corporations to inflate the credit bubble beyond the breaking point, this is how they know they inflated enough; inflating bubbles is the sole reason for organizing money corporations. Had business been conducted using accumulated capital, development would have been slower but crash would not have come.]The railroads of this country were overwhelmed with business. There was not an idle car in the United States when the panic struck us in 1907, and that panic came simply because the banks of the country were unable to meet the requirements of the law as to the reserves and they were compelled to withdraw credit.

---[ the law required the banks to keep reserves, the law did not require the banks to over-extend, to over-issue..... the law did not cause the panic, the bankers did......Senator Reed. You spoke of the railroads. That was true of every industry, was it not ?

Mr. Berry. Yes, sir.

In the year ending June 30, 1908, no new credit was created and $320,000,000 of existing credit was withdrawn. The deposit of $100,000,000 of Government funds in the banks, together with $100,000,000 of forced imports of gold and the withdrawal of $300,000,000 of credit, raised the reserve to 10 per cent in 1908, since which time it has again fallen to 8.2 per cent in 1912. The figures for 1913 are not at hand, but large exports of gold have been recently made, and the banks have been retrenching, which indicates that the reserve is now at or below the point of collapse in 1907.

It is my firm conviction that the credit situation of the United States is more strained than it was at this time in 1907 by reason of the fact that these $63,000,000 of gold has left the country, and some additional credit has been expanded. These facts clearly show the cause of our financial difficulties, and, in my judgment, completely exonerates the banks from all blame for it.

Judged by the work it does, our banking system is, in my opinion, the best in the world. The difficulty is wholly resident in the currency end of the system.

---[then, you got what you wanted: crash and burn, bubble and burst, since 1863; and now you want to give these banks more legal tender and less requirement for reserves to redeem their circulating credit.....Those are the two great factors in the currency of the Nation. Our currency is a compound, consisting, first, of legal-tender money uttered solely by national authority; and, second, of circulating credit mainly emanating from the banks.

Money is a resource or asset that is given by law a fixed power to extinguish debt. The credit that circulates with and in lieu of it is a debt or a promise to pay money. It is circulated by and for the convenience of those who create it, and it is received by the public on sufferance.

The proportion of credit, therefore, that can circulate at par with money depends upon the disposition of the people to voluntarily receive it. Experience in this country, as indicated in the table, shows that 100 per cent of credit to 10 per cent of cash in banks is about the highest proportion possible. The slightest hesitancy on the part of the banks in paying any kind of cash the customer wants increases the amount required.

The law fixes a lower proportion (100 to 12.5) in the banks over which the Government has supervision. The law also fixes the amount of money available in the country by designating the sources from which alone it may be supplied, and since the difficulty is resident in the scant supply the law alone can remedy it.

Now I take up the next question:

To enumerate concisely the advantages and disadvantages of the present system.

In answer to the first question I have described at length the one essential defect of the system. There are others, but they are trifling. The advantages of our present banking system are many.

First. It consists of about 26,000 independent banks widely distributed over an enormous territory, so wide indeed that collusion and monopolistic control are well-nigh impossible. Freed from the difficulty inherent in the scarcity of reserve money, competition among these banks for the privilege of extending credit would insure an equitable interest rate and a supply of credit equal to the demand.

---[why is your religious or sexual fascination with, and attachment to, the credit system ?]

This would allow our people to indulge their disposition to improve their condition without limit other than their ability and disposition to work.

Second. This system, comprising 26,000 banks, has been a natural growth answering a demand for banking facilities wherever it has appeared. These banks have an unimpaired capital of $2,000,000,000 and a surplus of more than $2,000,000,000. They carry $5,000,000,000 of quick assets (stocks and bonds) and are carrying nearly $20,000,000,000 of credit upon $1,500,000,000 of cash. They have established clearing-house facilities, local and general, that make their credit universally mobile with a trifling cost for exchange. They are capable of furnishing to the people of this Nation all the credit they need, and fail to do so solely because they are unable to convert their vast assets into new reserve money any faster than the gold supply will permit.

No new banking machinery is needed.

If any extension should be needed (as it will), the energy and initiative of the people will supply it when and where it is needed just as it has in the past. The experience of the past 10 years shows that the natural expansion of business in this country requires an annual increase of bank credit amounting to more than $1,000,000,000.

Senator Reed. You mean a billion dollars of new money ?

Mr. Berry. I mean new credits, new bank credits, discounts of paper, and other methods of established bank circulation.

Senator Shafroth. On the basis of eight to one, it would be about $125,000 of new legal-tender money.

Mr. Berry. In 1910 the banks extended $1,300,000,000 of new credit; in 1912, $1,150,000,000. Assuming that 10 per cent of legal tender is necessary to carry credit, the banks, collectively, must secure $100,000,000 of new legal-tender money each year to safely meet this demand.

---[according to you, the ever-increasing credit bubble should be furnished, by the government, with an ever-increasing legal tender fractional reserve; the more the banks inflate, the more the government should print.....?!?]It is the experience of 50 years that the banks can secure only one half of the new money that comes into the country; the other half remains in the hands of the people. It follows, therefore, that in order that the banks may secure $100,000,000, an increase of $200,000,000 must be made in the country each year.

---[why not keep all the money in the hands of the people? why force the people to borrow, at 6%, bank credit ? to pay 10 times 6% on each dollar that is used as fractional reserve for the credit bubble ?]Senator Shafroth. Mr. Forgan said that the building up of legal money was one to eight. That is the reason I said $125,000. You say one to ten.

Mr. Berry. Yes.

The most favorable view that can be taken of the prospect is that the annual average importation of gold for the last 32 years, which is $5,000,000 --you will find that in the Statistical Abstract. There are mutations --it goes in more rapidly one year than another. That will be continued, and that the highest yearly production of gold in the country, $90,000,000, will also continue. Thirty millions of this annual product is used in the arts, leaving $60,000,000 for coinage, to which add $5,000,000 imported, and we have $65,000,000 as the total possible annual increment from gold, as against $200,000,000 that the country needs.

In the presence of these facts it is no wonder that the banks do not respond to the demand for credit, for while they have $5,000,000,000 of quick assets it is impossible to liquefy them in sufficient quantities to do so. Nor is it surprising that an abnormally high interest rate obtains, nor that discrimination between borrowers leads to charges of conspiracy by lenders.

All of this is inevitable in the presence of a limited supply of credit which is forced by a limited supply of money. The banks have vast resources unimpaired (stocks and bonds), but are unable to increase reserves, and must refuse credit.

I now take up question No. 3, which is:

What are the chief purposes to be attained by an improved system ?

I answer that question as follows:

The chief purpose is to provide an unlimited supply of credit everywhere available, so that any man who has an asset to hypothecate as security can not only obtain credit upon it, but may do so in a market where competition among the bankers will insure him a just interest rate.

Bankers will readily extend credit when it is to their interest to do so, and since only a 10 or 15 per cent reserve is necessary, the conversion of a $150 asset bearing 4 or 5 per cent interest into cash will qualify them (without reducing their total of assets) to take on $1,000 of discounts at 6 per cent; but under existing conditions, where all the banks are loaned up (the conversion of the asset into new money being unlawful), the sale of the asset can not be made except at a sacrifice, and when sold by one bank to another does not help the general situation, since to qualify one bank to loan $1,000 has disqualified another.

There is no remedy along that line.

If there was a place where certain forms of bank assets (the public credit, for instance) could be converted into money, outside of the general market, bank reserves could be strengthened when needed, and the demand for legitimate credit met, the interest rate kept normal, and the general profit to bankers increased.

I will take up question No. 4, which was as follows:

Should national banks continue to have a bond-secured currency ?

I answer "no," and for several reasons.

First, this currency is of less value to the banks or to the community than the capital invested in the bonds would be if it was employed, as it should be, in the more proper and profitable forms of banking.

To illustrate: In round figures $700,000,000 of bank capital is invested in these bonds; $35,000,000 more of their cash is impounded in the redemption fund to which the Government finds it necessary to add $25,000,000 more; making $60,000,000 absorbed in maintaining current redemption for the notes issued against the bonds. $650,000,000, or 87.8 per cent of the entire issue, was thus redeemed in 1912.

We may assume that one-half of these notes are constantly loaned and earning 6 per cent for the banks, say $25,000,000 per annum, to which add $20,000,000 interest on the bonds, or $50,000,000 in all accruing to the banks on a total investment of $730,000,000, or a trifle less than 7 per cent per annum.

Now, if these bonds were sold to the Government for new legal tender United States notes, and the bank notes destroyed, the proceeds ($700,000,000) held in bank reserves would enable them to carry the five to seven billions of credit which is now needed and can not be granted, and from which at 6 per cent they would receive $300,000,000 per year, or six times the present return, while general business, using the credit, would reap a far greater return.

Second. The bank note is a mongrel in our currency. It is given, as I believe unjustly, certain monetary privileges and masquerades as money until it reaches the bank, where its real character is disclosed, and it runs immediately to the redemption bureau, for the sole reason that it is not money and can not stand in bank reserves.

Eighty-seven per cent of the entire issue runs back in a single year, and the 5 per cent fund of the banks being found insufficient, the Government furnishes the rest.

Third, a bank note secured by any kind of collateral is a form of credit; it is a promise to pay money, and therefore can not be justly or wisely given legal tender powers and made the basis of further expansion of credit or promises to pay money. There is no bottom to that pit. The piling up credit upon credit is dangerous, and therefore a remedy is not possible through the issue of credit notes of any kind.

---[yet you are highly recommending and advocating issuing bank-book entries at 10:1 ratio, at 6% interest.....]Every note or coin that carries legal tender power and circulates in the Nation should be issued by the General Government, not as a loan secured by bonds or any other collateral --for this is banking, and the Government should not engage in banking-- but by issuing it in exchange for an equivalent in value, just as the gold coin and gold certificate are issued. This is a Government function and can not be safely or lawfully delegated.

The bonded debt of the Nation in the hands of the banks is an equivalent in value to the money it represents. It is an evidence that an equivalent sacrifice has been made to the community by the holder of it, and, when surrendered, affords the most just and direct way to supplement the mining of gold and furnish the banks with the needed legal cash basis for their credit.

---[what sacrifice have banks (the holders of the bonds) made ? to what community?]I have shown, in answer to question No. 2, that in order to safely carry the billion of new credit that the Nation needs each year, $200,000,000 of new legal-tender money is necessary, and that only $65,000,000 can be secured from mining importation of gold. We must, therefore, either supply this deficiency with legal-tender paper or refuse to allow business to freely expand -- to adopt or practice another proposition, and say, "Hold on."

The only alternative is to reduce the required reserve of legal cash or put some form of credit currency in reserves with it, and thus invite disaster. The issue of credit upon credit in endless succession is to invite disaster and is entirely unnecessary.

Banking is not a governmental function. All the circulating credit, of whatever form, should emanate from the banks. The local bank is alone capable of determining the validity of the demand for or the value of the assets offered to secure credit in its vicinity, and should loan its credit on its own initiative and at its own risk, reaping the benefits and suffering the losses incident thereto. This credit will circulate by the sufferance of the people, because they find it more convenient and less expensive than money. It should -- and would, if enough could be carried by the banks -- automatically correspond in volume to the growing needs of the people.

It may be noted in passing that since the population is constantly growing and the scale of living constantly rising, that even a temporary shrinkage of credit can not occur unless forced by circumstances outside of the volitions of the people, so that if we remove this outside pressure we need have no concern about retiring any of it.

The sole cause of the failure of credit to expand in response to demand is the impossibility of securing sufficient reserve money to safely carry it. The sole cause of contraction is the effort of the banks to adjust the volume of credit to their scant reserves.

Bank notes, however issued, can not remedy this evil, unless they are given power to stand in reserves -- a travesty upon sound finance that would finally result in chaos.

If the essential difference between credit and money is held in mind, much of the confusion of thought on this subject will disappear. Credit arises out of the voluntary arrangements between individuals, and without the sacrifice of an equivalent in value.

For example, citizen A goes to banker B, and on giving security, directly or indirectly, is given a credit on the books of the bank, which he uses as currency while he still owns and uses the asset against which the credit was issued. In other words, he has the "cake and the penny too," having made no sacrifice whatever except the interest charge. Nor has the banker sacrificed anything beyond the use or impounding of the fractional reserve required to carry the loan, for which, and his service in cashing checks, he is receiving the interest.

On the contrary, legal-tender money is purely a creation of law, and the universal practice of sane lawmakers is to demand the absolute sacrifice of a full equivalent in value by the individual receiving it to the community issuing it.

For example, it is assumed that the effort involved in the production of 25.8 grains of gold is equivalent in value to a dollar of legal-tender currency, and the law provides that any person presenting that quantity of gold as evidence of this sacrifice, may have it coined into a dollar, but the gold must be sacrificed or devoted to the money used, and finally surrendered in exchange for other valuable things desired. The owner can not keep his gold as an ornament and use it as money at the same time; he can not have the "cake and the penny, too."

Money should always and only be thus issued, and when thus issued an overissue is not to be feared, unless the gold or other form of wealth thus used should by some fortuitous circumstance become accessible in large quantities without effort, in which case sane legislation would deny it the privilege of free coin.

A Government bond is an evidence of sacrifice just as surely as is gold or any other commodity. The concrete result of the sacrifice involved in acquiring a bond is not a piece of any one metal or thing, but is just as tangible in the form of Government machinery and the public works in general as is gold. The Panama Canal is just as useful to humanity and just as real as $350,000,000 of gold would be.

The community has received the benefit of the sacrifice involved in producing the bond in the form of a perpetual utility and may justly convert the bond into money --as justly and I think more wisely even than gold-- not by a process of hypothecation as security for bank notes, but by a process of coinage into legal-tender notes.

Senator Reed. I do not understand that last remark:---

Not by a process of hypothecation as security for bank notes, but by a process of coinage into legal-tender notes.

Senator Shafroth. That means the issue of legal tender.

Mr. Berry. That means the purchase by the Government of the bond before maturity with new legal-tender paper.

Senator Joseph Bristow. If I understand your position, it is, then, that the Government when it expends, as it has expended, $350,000,000 on this canal that it could have issued $350,000,000 of legal-tender notes---

Mr. Berry. No.

Senator Bristow. And paid the bills ?

Mr. Berry. No. I think, brother, if you will wait until I have finished you will get the answer to what is in your mind. No; that would not do at all. That is where we got to actually in war time. We issued money in war time in response to the exigencies of the war. We wanted to fight a battle, and we ground out a basket of money and fought the battle, regardless of where the money came from, and as a result we got more money than business could absorb, and it depreciated. It is not safe to put out money directly for public works. Build your canal with bonds, give your bonds or issue them to be converted at the will of the holder into legal tender, and then the money will come out in response to the demands of business, and no faster. That will be the result of this proposition as I see it.

I come now to question No. 5:

Should the present requirement of reserves for national banks be reduced, increased, or otherwise modified ?

I would like to have your especial attention to this. One of two things must be done -- and I think the whole problem is right there.

Senator Reed. State that again, please.

Mr. Berry. One of two things must be done: We must either reduce the required per cent of reserve, or make it easily possible for banks to maintain the present requirements without refusing or withdrawing credits.

The whole question of safety is raised by this consideration, and I would say at once that in the interest of general business any change made should be in the direction of greater safety rather than less.

The principal value of reserves, beyond the actual necessity for cash payment of checks, is to inspire the general public with confidence in the banks; and up to a certain point, at least, the larger the reserve known to be held, the less will be required, for when confidence is fully established nothing but the amount of cash physically necessary to pay current demands would be needed.

---[ speechless;This amount is variable, being greater in some places than in others, and varying in different seasons and different years in the same place, but never very large at any time or place, unless confidence is disturbed, in which case an enormous quantity may become necessary. It is a wise provision, therefore, to have an ample reserve of legal-tender money in all of the banks, and public supervision to announce it; and unless there is some compelling reason it should not be reduced. There is no such reason, but, on the contrary, there are many reasons why the present requirement should be maintained or increased.

I have shown, in answer to question No. 4, that the conversion of $700,000,000 of bank notes, which are now a burden upon reserves, into reserve money would largely increase the earning power of the banks without increasing or decreasing the total of their surplus assets, cash taking the place of the bonds therein. The notes are now a liability.

At the same time this would afford a basis for the credit needed in general business, so that a direct benefit would result inside and outside of the banks. An enormous increase in the safety of general business would result if the necessity for restricting credit was shown to be certainly and permanently removed.

I have no interest in any scheme that does not look to the prevention of panics and not to their amelioration after they are here. What we want is a preventive, something that will make it impossible for us to have a panic in the United States.

---[yet you are advocating the fractional reserve credit bubble system]From the standpoint of the banks the question of safety is not important. The banks are already safe; they have a constant inflow of maturing paper upon which they can compel payment in case of necessity.

Right here I might interpolate that there has been some discussion as to the difference between commercial paper and farm mortgages as a basis for rediscounting. The essential reason at the bottom of the opposition to the use of a farm mortgage for that purpose lies in this fact, in my judgment: With a commercial note involved, whose maturity is almost immediately at hand, somebody's notes are coming due every day. The bank can force the borrower to sell his stuff in a stringent market, whereas if the loan is put up on a mortgage, the mortgage can be sold, but the seller is the bank, and the banker does not want to sell it in bad market.

Senator Bristow. Mr. Berry, what we are undertaking to remedy is to provide the bank with the means by which it will not be necessary for it to force the maker of this note to sell his stuff on a stringent market and thereby bring about a depreciation.

Mr. Berry. That is exactly what we want to do. I agree with you perfectly on that, and the standpoint I have outlined here is at least looking in that direction. But I wanted to introduce the idea there, because, as I have said, at the bottom of the whole opposition to our fixed asset, like mortgages or bonds, lies in the fact that if the sale is to be made, the banker has got to make it and not the borrower.

Senator Shafroth. And if there is any sacrifice, the banker will take it ?

Mr. Berry. The banker will take it. On the other hand, as it is now, in the case of a stringency, the banker calls my note and says, "Mr. Berry, I want the money." "I have not got it." "Sell something; it don't make any difference whether you can get a good price for it or not, go and sell it and bring me the money." If it was a loan on a mortgage, and he was hard up for money and he had to have it, and the mortgage was not due to-day and he could not force me, he would have to go and sell it; and a mortgage is just as salable as any commercial paper, except that it falls to the other fellow; that is all there is to that, in my opinion.

---[the banker claims that one of the reason for interest is the risk he is taking; but when it comes to actually taking the risk, the interest-payer should take it ?!.....]Senator Shafroth. So that the banker must supply the same logic to himself that he does to others ?

Mr. Berry. So that the same logic must be applied to both. But this can only be done by forcing their customers to sell their assets on a strained market and often at a sacrifice. The banks are safe, but general business is never safe, and at irregular and unexpected intervals is made to suffer an enormous loss by the contraction of credit.

---[that is why business should operate on capital basis, not on credit basis; but that is beyond your intellectual horizon]A comparison of money quotations of bank stocks with fails or industrials on any given date will show a startling contrast. Bank stocks range far above par, some of them many hundred per cent, while the other stocks struggle to keep at par.

There is no valid reason why banking should be any more profitable than any other business, and it would not be if competition was as active behind the bank counter as it is in front of it. This would be the case if every bank could build up its reserve at will at the expense of its surplus assets.

---[The remedy lies, therefore, in providing the opportunity for the banks to easily maintain reserves rather than in reducing the required reserve. The only alternative, as I have said, is the restriction of the volume of business, and this is the cause of all our trouble.

There is a disposition to regard money held in reserve as inactive and practically useless. No greater mistake could possibly be made. The money in bank reserves is the most active and useful money in the counter. It makes possible ten times its volume in circulating credit, and without it our business would be decimated. The most important work that statesmanship can do is to make it easily possible to maintain it.

Mr. Berry. The next question is:

Should an elastic currency be authorized by law ? If so, should it be limited, and to what amount ?

The first question may be answered in the affirmative, for the reference is doubtless to the money factor in the currency, and money can only come into existence by the operation of the law. If we are going to have any currency, the law has got to do it, and it must be established by law, whatever it is.

Elasticity, in the sense that it will automatically increase in volume in response to, and only in response to, the legitimate demands of business, should be its chief characteristic.

Provision may be made for an automatic decrease in volume, but if it is issued under proper restraints it will never decrease in volume. If it is called out only in response to the growth of business, it can never retire unless the business diminishes, and business in this country is not destined to diminish. It never can diminish, except when forced to do so by the scarcity of money, and never will.

I wish to impress that thought upon this committee. If this money is issued under proper restraints it will never decrease in volume. If it is called out only in response to the growth of business it can never retire until the business diminishes and business in this country is not destined to diminish.

In a country covering the diversity of climate and conditions that this does business may and does experience local mutations of activity, but generally speaking there is no month in any year when the volume of business generally recedes. I have sought in vain to discover a period long or short in the recent history of the country when it was necessary to decrease the volume of money on account of a scarcity of business, but I have found many periods long and short in which business was of necessity withdrawn on account of scarce money. Elasticity "downward" or "inward" may be provided for, but it will never be used.

The credit factor in the currency emanating from the banks shows the same persistent disposition to expand and would constantly and regularly do so if an adequate supply of money to carry it was automatically supplied.

---[constantly supplying basis for a constantly increasing upside-down pyramid.....]To the second part of the question I would answer that it should not be artificially limited. If an adequate sacrifice is demanded in its issue, natural laws will regulate the volume automatically. A demand strong enough to overcome the resistance imposed by the sacrifice will alone be able to bring it out, and the continuance of the business that brought it out will keep it out. Elasticity, in the sense that any individual or clique, public or private, may exercise a controlling influence over the volume of currency, is not desirable.

The arbitrary fixing of the discount rate is a means to such control, and should be punished as a crime instead of being authorized by law. Competition on both sides of the bank counter is the only safe reliance for establishing the discount rates.

---[in your dream world]We need to disabuse our minds of the erroneous notion that the people can not be trusted to know when they are doing all the business they wish to do. When anyone offers satisfactory security for credit he should be able to get it in a competitive market, and he will be if we provide for the instant response in reserve-money volume to every such demand.

---[why not anyone who offers satisfactory security, should be able to borrow existing, accumulated legal tender ?]No sane man will borrow money on good security and pay interest for it unless he sees some way in which he can profitably use the money, and every such demand for money must be considered legitimate.

---[you purposely ignore the fact that banks do not lend legal tender, they lend credit; the sane man in your example is not borrowing money, he is borrowing bank credit.....]The so-called rigidity of bond-secured bank-note currency, or its failure to relieve a stringency by expanding, is charged to the fact that it is based on bonds of which there is a fixed amount. This is a mistake. The bond issue has never been fully used for note issues. Moreover, the extent to which it is now used is the result of pressure from the Treasury Department, and not natural voluntary expansion.

Again, when a stringency occurs, the retirement or contraction of the existing volume of bank notes, instead of expansion, occurs. Every time you have a stringency the bank note contracts and does not expand. This can not be due to the fact that it is based on bonds, but it is due to the fact that the bank note is a form of credit and not money.

---[and what is bank credit ? which functions as bank note ?]Whenever a stringency appears it is from the lack of reserve money upon which to carry credit, and the banks, in an effort to strengthen reserves, send in for redemption their holdings of bank notes other than their own.

Stringency always arises from an overissue of credit as compared to reserve cash, and bank notes, being the most readily liquidated form of credit existing --Uncle Sam pays if the issuing bank is tardy-- they are sent in for redemption first.

A moment's thought will show that this result is inevitable and reveals the cause of it. A banker finds that his reserve is depleted and must be restored.

---[now you are just lying: the banker does not find that his reserve is depleted, the banker finds that he over-issued, over-inflated the credit bubble, and he did that in spite of the law that sets his issue-limit; and a moment's thought reveals that to anyone]The only possible way to restore it is to call a loan. That is the only way he can build up his reserves; he must call a loan to build up his reserves. He has many loans that are drawing interest; all are in the process of maturing and can be called if necessary at maturity, but he finds that he has one loan that is fully matured and which is not drawing interest. It is in the form of bank notes other than his own, in the cash drawer, and to call it will not discommode his customers, so he sends it in for redemption, gets legal tender for it, and fixes up his reserve.

Senator Pomerene. You say he must "call" his loan. Is that strictly correct ? If it gets below the required reserve point, of course, that is the only way to build up his reserve, by calling a loan ? Another way is where his deposits accumulate without loaning out any more.

Mr. Berry. To refuse further loans ?

Senator Pomerene. Yes; refuse further loans.

Mr. Berry. Yes. I mean by "calling a loan"---

Senator Pomerene. I catch your point, but I thought you did not fully state it.

Mr. Berry. I put in a month's note to carry my business over the period in which I accumulate stock, and that period is six or seven months. At the end of the first three months I go there to get that note renewed. I want the banker to carry it another three months, and he says he can not do it. "Mr. Berry, you will have to pay me." That is what I mean by calling a loan.

---[ why not Mr. Berry return the credit entry that he received ?.....Senator Pomerene. Under that state of facts---

Mr. Berry. But the bank note does not interfere with any of his customers at all, and he fires that in first.

Senator Reed. But what Senator Pomerene meant was, that he might just let his present loan stand, but as people deposited then quit loaning, and the effect of that would be the same; that is, would have the same effect upon the commerce and business of the country. But now, let me understand you --were you through with that ?

Senator Pomerene. This reserve is simply against further loans; it may be used for the purpose of paying off the mortgages.

Mr. Berry. I do not catch that, Senator.

Mr. Berry. That is right. But the plan I propose would not have changed the gold situation at all and would have added $100,000,000 of new legal-tender paper to the circulation.

---[you obviously don't understand what you are saying. this new legal-tender does not go into circulation, it goes into the bank's vault and the banker's credit goes into circulation at 10x6%; and you clearly explain this in your next paragraph]Senator Reed. I do not understand your plan.

Mr. Berry. The plan is that the bank can take this $100,000,000 of bankers' notes to the Government, along with the bond, and say, "Here is your stuff; give me legal tender for it." It sells the bond and the notes both for $100,000,000 of legal-tender paper. Now, it takes that back, and it does not decrease the Government holdings at all. That money was made brand new by the printing-press for that special occasion; new money.

---[those bank-notes were promises to pay, why not take them back to the banks and make the banks pay what they promised? why buy these notes from them? why reward them for their activities ?]Senator Bristow. Now, what becomes of these notes of the bank ?

Mr. Berry. They are burnt up.

Senator Shafroth. That would be a substitution of one currency for another ?

Mr. Berry. Yes.

Senator Bristow. What does the bank give to get this legal-tender paper ?

Mr. Berry. Its $100,000,000 of bonds.

The Chairman. The bank has these bonds in the comptroller's office; and Mr. Berry proposes that those bonds shall be burned up and canceled, and that the bank notes assumed by the United States, as they come in, shall also be burned up, because these bonds belong to the Government. And the Government, in order to prevent contraction will issue in lieu of those national-bank notes as they are burned, legal tender of the United States.

Senator Reed. But why do that, when you have just told me that we did not contract the currency; we actually substituted good money for bad ?

Senator Shafroth. Because, in one instance, he referred to the fact that the bond was not presented for cancellation. In that event, there was no contraction. But if you say, "I want the bond and the whole circulating medium destroyed"---

Further Statement of William H. Berry, of Chester, Pennsylvania.

The Chairman. Mr. Berry, we will be glad to have you proceed.

Mr. Berry. As I remember, I finished discussing question No. 6 and my answer thereto, and I will now continue where I left off.

Senator Reed. Referring to your answer to question No. 6 I should like to ask just one question. Do I understand that you mean that in the crop-moving period, while there is a demand for money, a large amount of it to move the crops, and when the crops are moved that particular demand has ended that immediately there is some other counter-balancing demand---

Mr. Berry. The miller, for instance.

---[from the report of the Secretary we also know that the crops were moved in 1864 and in 1865, without the good offices of banks and their conjured up credit..... why not learn from that experience ?]Mr. Berry. I will now take up question No. 7.

Should such currency be the notes of individual banks, or of a central reserve association, or of a number of regional reserve associations, or of the United States Treasury ?

I answer that question as follows: The notes must of necessity be issued from the United States Treasury.

To be of any service whatever they must be clothed with legal-tender power --the power to extinguish debt-- and therefore competent to stand in bank reserves as a liquid asset.

Such notes can only be issued by the General Government. Even the sovereign States are forbidden by the Constitution to make anything but gold or silver legal tender.

If any bank is permitted to issue circulating notes, all banks should be permitted to do so; and all such notes should be purely credit instruments, devoid of all legal powers, and circulate, as other credit instruments --checks, etc.-- must do, on the sufferance of the public.

I do not think that such an issue would be profitable to the banks or desirable in the community. The maintenance of redemption for them would absorb as much or more of reserve money than would a similar amount of book credit.

In my judgment, the Government should issue all the notes as well as coins that are used in the country, and they should all be made a full legal tender for all debts, public and private, in the nation.

If there were no profit in issuing notes, the banks would not do it. If there is a profit in issuing notes --and there is-- it should revert to the Public Treasury, and not to private individuals or banks. Simplicity, economy, and justice would all be accomplished by this process.

Now, referring to question No. 8:

Should these notes be procured from the Treasury on pledge of security; and if so, of what should this security consist ? Should these notes be a first lien of the Government upon the assets of the association or bank to which they are issued ?

The notes should be procured from the Treasury on the surrender of an equivalent in value, just as gold certificates are procured by the surrender of gold.

In my judgment, the best form of equivalent to be surrendered is a Government bond.

The Government (all the people) have been the recipients of the benefits derived in creating the bond. The Government must pay interest upon it until maturity, and finally pay the individual that owns it the face of the bond.

The Government may justly buy it when voluntarily presented before maturity at the market price, and pay for it with new noninterest-bearing notes payable on demand in gold, to which notes legal-tender powers may be lawfully and justly given.

By a bond issue the Government (all the people) becomes indebted to a part of the people, the evidence being an interest-bearing time obligation. By this process of purchase the Government (all the people) is still indebted to a part of the people to the same extent, the evidence being a noninterest-bearing demand obligation circulating as money.

If this is done only on the voluntary solicitation of the bond holder, who finds that legal-tender money will be of more use or value to him than an investment at current interest rates, no possible injustice is done to him or to his debtor (the people); but a public necessity has been met, and the public has reaped a benefit in the cessation of interest.

If the note is never presented to the Government for payment, by reason of its loss or destruction or by reason of the continued necessity for its presence in bank reserves, the public gains not only the interest but the face of the note.

A private individual would find no advantage in thus converting a bond, for he already has a safe investment at current rates and can not improve it, but a banker would find it to his advantage to convert a $1,000 bond bearing, say, 4 per cent interest in order to qualify himself in the matter of reserves to take on a safe loan of $7,000 or $8,000 at 4 or 5 per cent.

An unsafe loan would not tempt him, so that the notes would automatically come into circulation in response, and only in response, to the legitimate demands of business, and would stay in circulation as long as business continued.

Manifestly, the banker would not convert a bond into money if his reserves were maintained by the voluntary deposit of newly mined or imported gold in his vaults by his customers, so that the mutations of gold production and movement would be met by an automatic adjustment of note issues. If gold increased, note issues would decrease, and vice versa.

I think the same reasoning could be applied to the mutations of current production, and that is the philosophy of the proposition, the mutations of current production. We have a constant in the production of gold, practically; we have a variant in the commodities which are measured by gold. Some years it is greater, some years it is less; so that as the constant is always deficient the supplement which should automatically come into existence would automatically come into existence, following this same reasoning in answer to the mutations of the production of notes, just as it would in answer to the mutations in the production of gold. It would supplement whatever the gold supply failed to produce.

These notes if issued as described would become a permanent part of the monetary circulation. They would never be presented for payment or for reconversion into bonds unless the production of gold became more than sufficient to supply the demand for reserve money, and this, I think, if it ever happens, will make it necessary to deny free coinage to gold.

These notes should be an obligation of the Government and not of the banks, and the question of preferred creditors of the bank is eliminated. In any event, if properly issued they would never be presented for payment, and it is mainly for this reason that the banks should not issue them.

Now I come to question No. 9. That is the most important question of the lot, gentlemen, and I want to have your attention. Should all currency be based on gold ? If so, how should it be issued, and what per cent of gold should be required ? And I answer that question in this way. In the sense of ready exchangeability, all currency should be based on gold.

Since gold is admitted by law to free coinage at a fixed price in all the important countries of the world, it affords an efficient means of maintaining the par of exchange so necessary to foreign commerce; and certainly the interchangeability of all our forms of money, each into the other at the will of the holder, is a necessity, for this and other reasons.

---[you can't imagine balanced foreign commerce (not trade for the sake of trade), in which money is not taken out of the country, but goods]All forms of money issued by the Government should be full legal tender for all debts, public and private, in the Nation, in which case, with free interchangeability, the most convenient forms would displace the less convenient, and finally an approach to stability of form would be reached and exchanges (redemption) reduced to a minimum. If all the forms were full legal tender, exchange of one form for another would be made only for convenience or export.

When the most convenient forms had finally been selected in proper proportion, exchanges would practically occur only for export, and since gold is recognized as coinable in all the foreign laws on the subject, gold would be sought for this purpose, and the Government should be prepared to exchange gold for any and every form of money at sight.

It should also continue to exchange notes for gold as now, at least until gold should become sufficiently plentiful to require its demonetization. Even then the existing coin should be exchangeable, for it would be the duty of the Government to maintain its gold coin at par with its paper money just as it now maintains its silver coin.

The automatic flow of gold from one country where money has fallen in value to another where it has risen (sufficiently to pay cost of transportation) maintains the par of exchange by a process not generally understood.

If prices rise or the value (purchasing power) of money falls in the United States below the average abroad, an automatic movement of money abroad is set up to restore the equilibrium or par, and gold, being the one factor or element common to all currencies, is the factor that moves, and in the case cited above gold leaves the United States and raises the value of the money that remains by decreasing the supply and reduces the value of foreign money by increasing the supply, so that gold is actually used in the world to dilute or reduce the value of money by its presence and increase its value by its absence.

The notion that currency derives its value from the value of gold is erroneous. Currency derives its value solely from the relative quantity in existence, and anything that serves the currency purpose in any degree is a factor. We have several factors in our currency. In 1913 it stood as follows:

Gold ......................... $611,000,000

Gold certificates .............. 943,000,000

Total gold ............................................. $1,554,000,000

Silver ......................... 215,000,000

Silver certificates ............ 469,000,000

Total silver .............................................. 684,000,000

United States notes ............ 350,000,000

Bank notes ..................... 705,000,000

Other bank credit ........... 17,085,000,000

Total bank credit ...................................... 17,790,000,000

Total currency .............. 20,378,000,000

Senator Reed. You count in checks ?

Mr. Berry. Count in checks, which circulate as exchanges. Any thing which is in process of fact exchange is currency.

The total gold is $1,554,000,000. The per cent of gold is 7.6.

The total legal-tender money in the currency is $2,588,000,000, including gold, silver, and United States notes, as against $17,790,000,000 of bank credit, or 14.5 per cent, and, unit for unit, the bank credit is more efficient in effecting exchanges than is money.

If we were to suppose that any one factor fixes the value of the rest, we must give the distinction to bank credit. Certainly, if we conclude that the value of gold gives value to all the rest, then it is a case of 7.6 per cent of tail wagging 100 per cent of dog, or 7.6 per cent of dog wagging 100 per cent of tail. (Difficult to believe in either case.)

As a matter of fact, the value of the commodity gold (bullion) is fixed by the value of currency into which it may be freely coined under the laws of civilized nations, two-thirds of the entire product being thus used.

The value of the currency is fixed by the quantity offered in exchange for other things, as compared to the demand (offering of other things in exchange) for it.

The great utility of gold as money is resident in the fact that it is made by law a factor in the various currencies of the world, and affords an automatic method of maintaining the par of exchange.

We need not discuss the primary reasons for the selection of gold for this purpose; they are well understood by students of the problem, but the fact must not be forgotten --gold is the one common factor in all civilized currency systems.

Gold redemption, therefore, must be a part of the plan for an extension of our legal-tender paper circulation, and the facts as to gold are therefore very important.

First. Forty-nine and eight-tenths percent of all our money (including bank notes) is gold or gold certificates. If we exclude bank notes, we find that 74 per cent of our legal-tender money is gold or gold certificates.

That our people prefer paper money to gold for daily use is proven by the fact that 57 per cent of all the gold in the country has been "redeemed" or exchanged for certificates. The remaining 43 per cent is mainly lying in reserves. Comparatively little of it is in active circulation in the hands of the people.

The issue of gold certificates in 1912 was $45,000,000, while only $43,000,000 of gold was added to our stock. Three million dollars of the old stock went into certificates with all the new. Gold will only be sought for export.

Second. The annual requirements for gold export average nothing. For the past 32 years we have imported an average of $5,000,000 per year.

The largest net export of any year was $89,000,000 in 1864; that was during the war. So that in an experience of 50 years the export of gold is seen to be a negligible quantity.

It would be extravagantly safe to assume that $150,000,000 might be needed for this purpose in any one year, and equally safe to assume that an average of $20,000,000 per year of gold exports would be the limit for any extended period. For the past 32 years an average of $5,000,000 per year has been imported.

We have an annual production of $90,000,000, $60,000,000 of which is available for money, or three times the possible average export. The ability of the Nation, therefore, to "redeem" its full legal-tender paper in gold is so well assured that we need give the matter no concern.

Third. The necessary annual increment of legal tender in the country is (as we have seen in answer to question No. 2) $200,000,000 and the annual increment of gold is $65,000,000. The increment of legal-tender paper needed, therefore, is $135,000,000 per year, of which the gold increment ($65,000,000) is 49 per cent.

On June 30, 1912, we had in circulation:

United States notes .................. $340,000,000

Silver dollars ......................... 70,000,000

Gold certificates ..................... 943,000,000

Silver ................................ 469,000,000

Subsidiary silver ..................... 145,000,000

Total ............................... 1,967,000,000

All of which may be considered redeemable in gold. Neglecting entirely the silver held in the Treasury as an asset, we had of gold at the same time:

In Treasury reserves .................. $1,093,000,000

In circulation ................ 610,000,000

Total gold ...................... 1,703,000,000

All of which was available for redemption purposes, or 86 per cent of the total redeemable currency.

If we eliminate the subsidiary silver, and the $1 and $2 notes, no part of which can be spared from actual use, we find that more than one-half of our money is gold. In other words, we have 100 per cent of gold back of our uncovered money, of which $1,093,000,000 is already assembled in the United States Treasury for redemption purposes, and amounts to 85 per cent of our redeemable currency.

Starting, therefore, with 85 per cent of gold money in the redemption fund, and currently securing 49 per cent of gold against the new notes to be issued, we would seem to have a competent equipment with which to face a situation in which in the long run no redemption would be required, and in which in all human probability the deposit of gold in exchange for the more convenient forms of paper must increase more rapidly than in the past.

In answer to the second part of this question, I would say that the new currency should be issued by the Treasury Department in exchange for an equivalent in value of Government bonds, whenever and by whomsoever presented, the bonds to be canceled as fully paid.

The notes should be full legal tender for all debts public and private in this country, and redeemable in gold or any other form of currency issued by the Government on demand.

A minimum reserve fund of gold coin amounting to 20 per cent of all outstanding currency other than gold should be maintained in the Treasury, the same to be replenished when necessary by the sale of bonds for gold in the open market.

Since a constant increment of 49 per cent of gold automatically accompanies the proposed expansion of notes, which increment flows of its own volition into the reserve fund, it is altogether probable, if not certain, that the gold reserve will constantly increase, and no bond sale for this purpose would ever occur.

I mean a 20 per cent reserve here as a minimum. You can put it up as high as 33 per cent. You can not maintain it above that and furnish the country with the money it needs.

Senator Shafroth. There is not enough gold.

Mr. Berry. Yes, sir; there is not enough of it.

Now I pass to question No. 10.

If notes are issued to or by an association what should be the limit in amount of this currency for each association, and should this limit be based on its capital stock and surplus ?

I now answer that question in this way. No notes should be issued by a bank or association. If thus issued, they can not be given legal-tender powers, and would be useless otherwise. If issued to an association or bank by the Government in exchange for an equivalent the question of capital and surplus is not pertinent.

---[bank-book credit-entry functions as a bank-note....; what equivalent money corporations have in exchange for government-issued legal tender ?]Senator Reed. Why is not capital and surplus pertinent ?

Mr. Berry. Suppose I sell you a horse for $150; I do not care whether you have any capital or assets or not, as long as you pay for the horse.

Senator Reed. Yes; but we are not dealing with horses.

Mr. Berry. We are dealing with assets just like horses, only better.

Senator Reed. What kind of assets ?

Mr. Berry. Government bonds.

Mr. Berry. It is only when we introduce the idea of Government loaning money to the banks that the question of security enters the problem, but as a matter of fact if the money issued either as a loan (however secure) or as an equivalent to the asset (bond) surrendered, and only in answer to the demands of business, final payment will not and can not be made unless business is reduced, and business should not and will not be reduced. Therefore the security will only cover the interest payment. The final result will be a perpetual debt and interest payment by the people to the banks and by the banks to the Government (the people), and a horde of clerks to attend to an utterly useless and fruitless mass of detail.

---[but you do recommend that the people perpetually pay interest to the banks for the use of bank credit, and that the people pay legal tender to the banks for bank credit]If the money is issued, as are the gold certificates, in exchange for an equivalent, the question of capital and surplus is not pertinent, and no bookkeeping is involved.

Mr. Berry.

I now take up questions Nos. 13 and 14, referring to the new Federal reserve banks. It is my opinion that no new banking machinery is needed. The issue of money is a Government function, and the Government is already provided with all the machinery needed for this purpose.

The conduct of general business, including banking, is a matter for the people to inaugurate and manage and should meet with as little interference from the Government as possible.

It is only where monopoly is necessarily inherent in a business activity that Government should interfere. Banking is not such an activity, and to secure publicity as to the condition of financial institutions is as far as Government should go in controlling them. Conspiracies among them for the purpose of limiting credit or fixing the interest rates should be treated as crimes and punished under the Sherman law.

---[on the contrary: the banking system is one, even if there are 26,000 individually owned money corporations in it; monopoly is inherent in banking, and you should have noticed it by now (after 25 years of writing articles on it)]Now, referring to questions 16 to 22, inclusive, with reference to the new Federal reserve banks: In my opinion no new banking machinery is needed. It can serve no useful purpose and will involve a horde of new officers and clerks at high salaries and put an added burden on credit, which the borrower must finally pay.

The banking system of the country as now constituted, with clearing-houses in the principal cities of every "region" in the country, is competent to handle all the credit the country needs. Scarcely an individual bank in the country is handling more than half the business it could handle if reserve cash could be readily secured. Credit would be thus reduced to cost instead of increased.

Question No. 23 is:

Should Government deposits be withdrawn from banks and placed with the reserve associations; and, if so, how should they be apportioned and what rate of interest, if any, should be paid ? Within what time could this be safely done ?

All Government funds, excepting possibly a small working balance, should be deposited in banks on uniform approved security at interest rates established by competition.

The absorption of money in the Treasury in times of plethoric revenue is an evil. It now causes a depletion of reserves and contraction of business. Under a new law providing for the issue of new legal tender, as I have described, the withdrawal of money into the Treasury would cause an unnecessary issue of new money which might become redundant in case of subsequent large disbursements.

---[How was it between 1846 and 1860, when the government managed to get by without the good offices of banks; kept its monies in the independent treasuries; received and paid out money directly; received and paid out gold, silver and treasury notes ?]The Government should use the banks as other interests do. With your permission, I will elaborate that statement a little.

Senator Reed. What question are you referring to now ?

Mr. Berry. No. 23.

Senator Shafroth. It is his answer to the twenty-third question.

Mr. Berry. When I was treasurer of the State of Pennsylvania, I had $20,000,000 of State funds in my hands all during that period.

Senator Shafroth. During what period ?

Mr. Berry. During the period of my incumbency-- two years.

Senator Shafroth. What years do you refer to ?

Mr. Berry. I refer to 1906 and 1907, during the panic. I had that money deposited in the various banks in my State, and the law fixed the interest rate at which I must deposit this money at 2 per cent and prescribed the various kinds of security I must take for it, but I was absolutely without information as to where that money was most needed in my State. I had nothing but the importunity of the bankers to guide me. The fellow that was loudest mouthed and put up the biggest holler got the money. But inevitably as soon as I deposited that money at 2 per cent it instantly flowed to the spot that needed it most and where the highest interest was paid. I traced it. I put $100,000 in a bank in the northern part of the State, and inside of three days that same $100,000 landed in Pittsburgh. This man was paying 2 per cent for the $100,000, and he was getting 4 per cent from the Pittsburgh bank. The Pittsburgh bank would not pay my checks. They had $5,000,000 of my money and would not pay my checks. I had the severest experience I ever had in my life during that panic. I had $5,000,000 tied up, and I could not get a dollar for four months.

---[In an independent treasury the money would always have been yours, always at your disposal....]Senator Reed. I take it, though, that your idea is that it was unjust to give advantages to a bank that did not need it when there was a bank that needed it so badly.

Mr. Berry. Yes.

Senator Reed. But I call your attention to this fact: The bank that you did let have the money was a bank that had not repudiated its checks, and when that bank put its credit back of the loan or advancement from the State treasury---