William Harrison, President

Levi Morton, Vice-President

William Windom, Secretary of the Treasury

Treasury Notes and Silver Bullion.

The President pro tempore. Is there further morning business ? If there be none, that order is closed, and the Chair lays before the Senate the unfinished business, being the bill (S. 2350) authorizing the issue of Treasury notes on deposits of silver bullion.

---[ It became law on July 14, 1890, and was known as the "Sherman Silver Purchasing Act," it declared that every month the Secretary of the Treasury should purchase 4.5 million ounces of silver and issue Treasury notes for it; it superseded the 1878 Bland-Allison Act; in 1893, with the active co-operation of Democrat president Cleveland, it was repealed.The Senate, as in Committee of the Whole, resumed the consideration of the bill.

Mr. Sherman. Mr. President, if no Senator on the other side of the Chamber desires to address the Senate, I will avail myself of this opportunity, though I did not intend to speak upon this question until a later stage, when we had some bill supported by somebody to debate. The bill that was reported from the Committee on Finance seems to me like an uneasy ghost, wandering without an owner or a father, without compass or without guide, with no one to call for a vote and no one to demand a solution of the difficult question with which it assumes to deal. Still, as I am compelled to be absent from the Senate Chamber on other important business of the Senate, I will avail myself of this opportunity to say what I have to say rather than at some future-time, when it may interfere more with the public business.

I approach the discussion of this bill and the kindred bills and amendments pending in the two Houses with unaffected diffidence. No problem is submitted to us of equal importance and difficulty. Our action will affect the value of all the property of the people of the United States, and the wages of labor of every kind, and our trade and commerce with all the world. In the consideration of such a question we should not be controlled by previous opinions or bound by local interests, but, with the lights of experience and full knowledge of all the complicated facts involved, give to the subject the best judgment which imperfect human nature allows. With the wide diversity of opinion that prevails, each of us must make concessions in order to secure such a measure as will accomplish the objects sought for without impairing the public credit or the general interests of our people. This is no time for visionary theories of political economy. We must deal with facts as we find them and not as we wish them. We must aim at results based upon practical experience, for what has been, probably will be. The best prophet of the future is the past.

To know what measures ought to be adopted we should have a clear conception of what we wish to accomplish. I believe a majority of the Senate desire, first, to provide an increase of money to meet the increasing wants of our rapidly growing country and population and to supply the reduction in our circulation caused by the retiring of national-bank notes; second, to increase the market value of silver, not only in the United States, but in the world, in the belief that this is essential to the success of any measure proposed, and in the hope that our efforts will advance silver to its legal ratio with gold, and induce the great commercial nations to join with us in maintaining the legal parity of the two metals or in agreeing with us in a new ratio of their relative value; and, third, to secure a genuine bimetallic standard, one that will not demonetize gold or cause it to be hoarded or exported, but that will establish both gold and silver as standards of value, not only in the United States, but among all the civilized nations of the world.

Believing that these are the chief objects aimed at by us all and that we differ only as to the best means to obtain them, I will discuss the pending propositions to test how far they tend, in my opinion, to promote or defeat these objects.

And, first, as to the amount of currency necessary to meet the wants of the people. The paper money in actual circulation, which is the active money in nearly all domestic transactions in the United States, consisted of the following items on the 1st day of May, 1890:

Legal-tender United States notes ............................. $346,881,016

Certificates of deposit ........................................... 8,795,000

Gold certificates (less amount held in Treasury) .................... 134,642,839

Silver certificates (less amount held in Treasury) ................. 292,923,348

Old demand notes ........................ 56,442

Fractional currency ...................... 6,912,549

National-bank notes ....................... 189,442,472

Total ................ 979,453,667

The aggregate of $979,000,000 is subject to a reduction of notes lost or destroyed by the casualties of time, of which it is hard to make an estimate. The fractional currency and demand notes may be considered as out of circulation, though a part of them will be presented for redemption. The gold and silver certificates, being of recent origin, may be counted as outstanding. The United States notes have been in circulation for twenty-seven years. The estimated loss, according to the present Treasurer of the United States, is about 2 per cent. The loss of bank-notes inures to the benefit of the United States and is estimated to equal or exceed that of United States notes. If these estimates can be relied on, the volume of currency is diminished by lost notes about $12,000,000 leaving of paper money outstanding $967,000,000.

But it must be remembered that, of the $189,000,000 of national-bank notes outstanding, $60,521,556 is in process of redemption and cancellation, and that the same amount of lawful money is held in the Treasury to redeem these notes. It is manifest that both sums should not be counted as in circulation, thus reducing the aggregate of paper circulation to $907,000,000. To this must be added the gold and silver now in circulation.

As to silver coin, it can be stated with substantial accuracy as follows:

Standard silver dollars in circulation October 1, 1889 ......................... $57,554,100

Subsidiary silver coin in circulation October 1, 1889 ............................ 52,931,352

110,485,452

As to gold coin in circulation, the estimate of the Secretary of the Treasury at the same date, October 1, 1889, was $375,947,715 and his estimate of total circulation at that date was $1,405,018,000.

While some of these estimated items, especially that of gold in circulation, may be subject to many grains of allowance, it is reasonably certain that the current money in use in the United States is now about $1,400,000,000. In this sum I do not include the gold and silver coin in the Treasury represented by certificates in circulation. And it must be remembered that much of this sum of $1,400,000,000 is held in the Treasury and in banks as reserves required by law. Is this volume of current money sufficient for the foreign and domestic exchanges of the people of the United States ? I concede that, by reason of the great extent of our country, its vast diversified productions, its increasing population, and the push and energy of our people, they need a larger circulating medium than an equal number in an older and more densely populated country. But nowhere else are the substitutes for money better understood and in more general use.

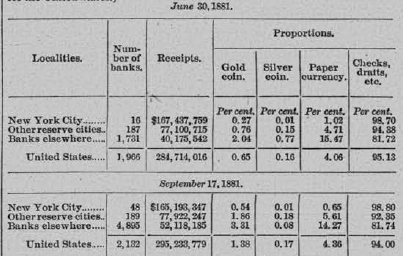

From a table for the first time compiled in the year 1881 from actual returns from all the national banks, it was found that the receipts of those banks upon a single day were $295,000,000, while the receipts of the banks in New York and Chicago were more than one-half of that amount. These data also show that the proportion of gold coin received was less than 1½ per cent.; of silver, less than one-fourth of 1 per cent.; of paper money less than 5 per cent., and of checks and drafts about 95 per cent., while the proportion of the receipts of the banks in New York City was more than 98 per cent. in checks and drafts and less than 2 per cent. in coin and paper. If the daily receipts or payments of the banks of the country were to be made exclusively of gold and silver coin, the total coinage of the year, amounting to $60,000,000, which kept employed in its manufacture the whole force of the Mint of the country (consisting of a small regiment of men) during the entire year, would be sufficient only to supply the banks of the country in making payments for one-third of a bank day, or one hour and forty minutes, so that the money of the country has very little proportion to the business of the country.

The total amount of coin manufactured at the mints in a year, if used exclusively in making payments, would be exhausted by the national banks of New York and Chicago in less than a single day. The whole of the coin and currency of the country now in circulation, $1,400,000,000, would supply the national banks of the country, if their payments were made exclusively in coin and currency, for five days only.

The table referred to is as follows:

Table from report of the Comptroller of Currency for 1881, showing total receipts and proportions of gold coin, after coin, paper money, and checks and drafts.

[In this table are shown, both for June 30 and for September 17, the proportions of gold coin, silver coin, paper money, and checks and drafts, including clearing-house certificates, to the total receipts in New York City, in the other reserve cities, and in banks elsewhere, separately, and also the same proportions for the United States.]

This table shows the proportions of money of different kinds, checks, drafts, etc., that are paid in the ordinary business of the country, showing that the actual circulation plays a very insignificant part in the business of this country. Besides, the use of banks and banking institutions of every grade and degree is more common in the United States than anywhere else. In every town of any importance in the United States there are banks of issue or banks of exchange or banking offices or savings-banks or institutions of a similar character for the care and deposit of money in the transaction of monetary business, greater in number and in aggregate than all the institutions of the kind in Europe. Thus there has grown into the customs of the country the use of credit money in the form of drafts, checks, and certificates to a far greater extent than anywhere else, leaving money in circulation to transact only the smaller business of the country.

The best way to test the sufficiency of this sum of $1,400,000,000 to conduct the business of our country is to compare the volume of the currency to-day with that of former periods. In making this comparison I do not take a period before the war, when we had practically no national currency but gold and silver coin, and that in comparatively very small amounts. This was at a time when a great party was dominant which denied the power of the United States to issue any form of paper money, and under the pretense of States' rights crippled the Government of many of the essential rights of a nation and left to the several States the imperial right to issue paper money through private corporations. It is a marvel that the country grew into such proportions with a currency so vicious, insecure, insufficient, and at times worthless as State-bank paper money. It did grow in spite of it, but no student of American history would propose a recurrence to such a policy. Our currency was then the worst existing in any commercial nation, but the necessities of the war and more liberal opinions as to the powers and functions of the National Government led to restrictions upon State paper money and the adoption of national paper money, which is now conceded by the most advanced nations as the best ever devised by man.

Let us take a period when this national policy was well established. On the 1st of March, 1878, before resumption, and at the date of the passage of the silver act, the aggregate currency in circulation was $805,793,807, including $80,000,000 of gold, or $600,000,000 less than now, being $16.50 per capita, while now it is $22 per capita.

On the 1st of October. 1880, after resumption and at a time of great prosperity, the total amount of paper money in circulation, exclusive of that held in the Treasury, was $690,430,147, as follows:

United States notes ............. $329,417,403

National-bank notes .............. 340,329,453

Silver certificates ............... 12,203,191

Gold certificates .................. 7,480,100

690,430,147

This included only $12,200,000 of silver certificates and $7,480,000 gold certificates. Now we have $292,000,000 of silver certificates and $134,000,000 gold certificates, but the national-bank circulation was then $344,505,427 and is now $189,000,000.

During all this period the volume of money in actual circulation was increasing. I here present a table showing that each and every year from 1878 to this year the currency of the country in actual circulation has been increasing year by year more than the population has increased.

Mr. Teller. Will the Senator tell us how much it actually increased last year ?

Mr. Sherman. The statement----

Mr. Teller. I challenge the statement that the Senator makes and I want him now to tell us.

Mr. Sherman. I know the Senator challenges everything, but I take this from the Treasury report, the highest authority we can quote in this country. Here is the table---

Mr. Teller. If the Senator will allow me, I will call his attention to the fact that the Secretary's report shows that the circulation increased last season less than $8,000,000, and that certainly does not bear out his statement that it has increased as fast as the population.

Mr. Sherman. I do not think this way of interrupting an argument a very good one, but I think the Senator is not correct. I have the statement here before me, and I will read it to him, although I did not intend to weary the Senate with going over all these figures. The increase each year, in the different kinds of money, is exhibited in the following table:

The amount and kinds of money in actual circulation on certain dates from 1878 to 1889.

Mr. President, this is the best information we can have, and if we can not rely upon the official reports of the officers of the Government, what can we rely upon ? What newspaper scrap should be brought here to face down figures like these ?

Mr. Teller. If the Senator will allow me, I will---

The President pro tempore. Does the Senator from Ohio yield ?

Mr. Sherman. I do not like to yield and I do not like to refuse.

Mr. Teller. I do not want that statement to go out uncontradicted.

Mr. Sherman. Since the Senator takes it in that way, I will go on.

Mr. Teller. Very well; I will contradict it by the record when the Senator gets through.

Mr. Sherman. That is a great deal better, and it is a much more orderly way of proceeding in the Senate.

It is a fact that there has been a constant increase of currency. It is a fact which must be constantly borne in mind. If any evils now exist, such as have been so often stated, such as falling prices, increased mortgages, contentions between capital and labor, decreasing value of silver, increased relative value of gold, they must be attributed to some other cause than our insufficient supply of circulation, for not only has the circulation increased in these twelve years 80 per cent., while our population has only increased 36 per cent., but it has all been maintained at the gold standard, which, it is plain, has been greatly advanced in purchasing power. If the value of money is tested by its amount, by numerals, according to the favorite theory of the Senator from Nevada [Mr. Jones], then surely we ought to be on the high road of prosperity, for these numerals have increased in twelve years from $805,000,000 to $1,405,000,000 in October last and to $1,420,000,000 on the 1st of this month. This single fact disposes of the claim that insufficient currency is the cause of the woes, real and imaginary, that have been depicted, and compels us to look to other causes for the evils complained of.

I admit that prices for agricultural productions have been abnormally low and that the farmers of the United States have suffered greatly from this cause. But this depression of prices is easily accounted for by the greatly increased amount of agricultural production, the wonderful development of agricultural implements, the opening of vast regions of new and fertile fields in the West, the reduced cost of transportation, the doubling of the miles of railroads, and the quadrupling capacity of railroads and steam-boats for transportation, and the new-fangled forms of trusts and combinations which monopolize nearly all the productions of the farms and workshops of our country, reducing the price to the producer and in some cases increasing the cost to the consumer. All these causes co-operate to reduce prices of farm products. No one of them can be traced to an insufficient currency, now larger in amount in proportion to population than ever before in our history.

But to these causes of a domestic character must be added others, over which we have no control. The same wonderful development of industry has been going on in other parts of the globe. In Russia, especially in Southern Russia, vast regions have been opened to the commerce of the world. Railroads have been built, mines have been opened, exhaustless supplies of petroleum have been found, and all these are competitors with us in supplying the wants of Europe for food, metals, heat, and light. India, with its teeming millions of poorly paid laborers, is competing with our farmers, and their products are transported to market over thousands of miles of railroads constructed by English capital or by swift steamers through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, reaching directly the people of Europe whom we formerly supplied with food. No wonder, then, that our agriculture is depressed by low prices, caused by competition by new rivals and agencies. Any one who can overlook these causes and attribute low prices to a want of domestic currency, that has increased and is increasing continually, must be blind to the great forces that in recent times throughout the world are tending by improved methods and modern inventions to lessen the prices of all commodities. A surplus of a very small percentage of an article that will perish within a year, as a matter of course, depreciates the value of the whole stock on hand. It is very unlike the effect upon an article of permanent and enduring value like the metals. The reasons why the products of labor have cheapened in price are thus forcibly stated by C.P. Williams in a recent number of Rhodes's Journal of Banking:

The advance in the wages of labor proves that gold has not appreciated. And the wages of labor have advanced at the same time that the products of labor have cheapened in price. Why, the past half century, and more particularly the past quarter century, has revolutionized commerce and production: first, by inventions and machinery and steam power in aid of productiveness of human labor; second, by steam-ships taking the place of sails on all the lines of ocean commerce, shortening the time of the voyage and cheapening the cost of transportation and commercial intercourse; third, by the net-work of railways through all the more progressive countries, diminishing the cost of internal transportation and intercourse to one-fourth the former cost in both time and money; fourth, in belting both the continents and the seas with the telegraph, by which we have at our breakfast-table the news of yesterday from the most distant corners of the Earth, formerly taking six months to reach us; fifth, by our improved method of exchanges, lessening by three-fourths the actual quantity of money --gold and silver-- used by commerce, and thereby lessening its cost.

These improvements, the result of advanced civilization and of fertile invention, are recognized by all intelligent economists and statesmen as fully accounting for the cheapened price of commodities, while human labor advances in its reward, and gold as well as silver depreciates in value. As Mulhall, the english statistician, says: "It would be monstrous if prices remained the same in spite of cheapened transport, improved machinery, and all the effects of scientific progress."

The farmer will really see, in view of this recital, how his interests are affected. If his products are somewhat reduced in value, so are all articles of his consumption cheapened in still greater ratio.

A rapid or unexpected fall or rise in prices of agricultural productions is not a new experience in our country or in other countries in the world. Nothing is more uncertain in price than the perishable articles which form the common food of mankind. In my own experience I have seen the price of wheat fall in Ohio as low as 50 cents and rise to $2 without any apparent appreciation or diminution of the currency. Some fifty years ago a very popular and excellent man was a candidate for the Legislature in Ohio and his election was supposed to be assured, but an advertisement was found in a local paper of some twenty or thirty years before that time, in which he, as a miller, offered to pay 30 cents a bushel for wheat in cash. This ofter was thought so illiberal that the candidate was easily beaten, although when the facts were known it was shown that he offered to pay the market price, 30 cents, in cash, while all other bidders would only give 30 cents in store pay.

These fluctuations depend upon the law of supply and demand, involving facts too numerous to state, but rarely depending on the volume of money in circulation. An increase of currency can have no effect to advance prices unless we cheapen and degrade it by making it less valuable; and if that is the intention now, the direct and honest way is to put fewer grains of gold or silver in our dollar. This was the old way, by clipping the coin, adding base metal.

If we want a cheaper dollar we have the clear constitutional right to put in it 15 grains of gold instead of 23, or 300 grains of silver instead of 412½, but you have no power to say how many bushels of wheat the new dollar shall buy. You can, if you choose, cheapen the dollar under your power to coin money and thus enable a debtor to pay his debts with fewer grains of silver or gold under the pretext that gold or silver has risen in value, but in this way you would destroy all forms of credit and make it impossible for nations or individuals to borrow money for a period of time. It is a species of repudiation.

The best standard of value is one that measures for the longest period its equivalent in other products. Its relative value may vary from time to time. If it falls, the creditor loses; if it increases, the debtor loses; and these changes are the chances of all trade and commerce and all loaning and borrowing. The duty of the Government is performed when it coins money and provides convenient credit representatives of coin.

---[Yes; government (alone) should provide the promises to pay coin !!! You should print that at the front door of every bank.]The purchasing power of money for other commodities depends upon changing conditions over which the government has no control. Even its power to issue paper money has been denied until recently, but this may be considered as settled by the recent decisions of the Supreme Court in the legal-tender cases. All that Congress ought to do is to provide a sufficient amount of money, either of coin or its equivalent of paper money, to meet the current wants of business. This it has done in the twelve years last passed at a ratio of increase far in excess of any in our previous history.

Surely, if an abundance of good money constantly increasing in volume, all equal to gold, is the elixir of life in our trade and commerce and should bring prosperity to our people and good prices and good markets for our farmers, now would be the good time come; but experience has shown that the prices have fallen as our currency increased. Nor can it be said that industries are idle or that the country has not reasonably prospered in general growth and production.

Still it is apparent that there is a general feeling in the country that Congress ought to provide for additional circulation, or, at least, supply a substitute for the national-bank notes being rapidly retired. The sole cause of this retirement is the payment by the United States of its bonds held as security for the notes of national banks. Congress has repeatedly refused to allow these banks to issue notes to the amount of the real value of the bonds deposited, or even to their face value, and has steadily shown its opposition to the system of national banks by refusing to pass any measure of relief, however just and meritorious, so that the friends of the national-bank system feel that its end is near at hand.

The 4½ per cent. bonds, amounting to $112,521,250, will mature next year, and the 4 per cent. bonds, amounting to $606,551,000, will mature in 1907 and be paid, leaving no basis for the national-bank system, and there is no disposition on the part of Congress to prescribe any other security for circulating bank notes. We must then legislate in view of the fact that the $60,000,000 of national-bank notes now outstanding and secured by a deposit of lawful money must soon be paid off, that the circulating notes based upon 4½ per cent. bonds will probably be retired within a year, and that the balance of the circulating notes, amounting on April 30 to $128,920,910, will be retired prior to 1907. This fact alone compels us to provide for some substitute for these circulating notes.

Under the law of February, 1878, the purchase of $2,000,000 worth of silver bullion a month has by coinage produced annually an average of nearly $3,000,000 a month for a period of twelve years, but this amount, in view of the retirement of the bank notes, will not increase our currency in proportion to our increasing population. If our present currency is estimated at $1,400,000,000 and our population is increasing at the ratio of 3 per cent. per annum, it would require $42,000,000 increased circulation each year to keep pace with the increase of population; but as the increase of population is accompanied by a still greater ratio of increase of wealth and business, it was thought that an immediate increase of circulation might be obtained by larger purchases of silver bullion to an amount sufficient to make good the retirement of bank notes and keep pace with the growth of population. Assuming that $54,000,000 a year of additional circulation is needed upon this basis, that amount is provided for in this bill by the issue of Treasury notes in exchange for bullion at the market price. I see no objection to this proposition, but believe that Treasury notes based upon silver bullion purchased in this way will be as safe a foundation for paper money as can be conceived.

Experience shows that silver coin will not circulate to any considerable amount. Only about one silver dollar to each inhabitant is maintained in circulation with all the efforts made by the Treasury Department, but silver certificates, the representatives of this coin, pass current without question and are maintained at par in gold by being received by the Government for all purposes and redeemed if called for. I do not fear to give to these notes every sanction and value that the United States can confer. I do not object to their being made a legal tender for all debts, public or private. I believe that if they are to be issued, they ought to be issued as money, with all the sanction and authority that the Government can possibly confer. While I believe the amount to be issued is greater than is necessary, yet in view of the retirement of bank notes I yielded my objections to the increase beyond $4,000,000. As an expedient to provide increased circulation it is far preferable to free coinage of silver or any proposition that has been made to provide some other security than United States bonds for bank circulation. I believe it will accomplish the first object proposed, a gradual and steady increase of the current money of the country.

But this measure can be greatly aided by a proper treatment of the national banks. These banks have fully met all expectations. They have furnished circulating notes without cost and without loss to the Government or people of the United Slates.

---["Without cost" ?!?! You expect anyone to believe that ?!The total tax collected from the national banks up to July 1, 1889, amounted to $7,855,887.74 on capital, $60,940,067.16 on deposits, and $68,868,180.67 on circulation, making a total of $137,664,135.57, besides full taxes to the States and cities and towns where located. ---[How much did it cost to the tax-payers ?] No system of banking has ever been more successful. It is distributed through all parts of the country, is free and open to all without limit. Its strength is in United States bonds deposited as security for the notes, its weakness is in the rapid payment of these bonds and the difficulty of finding a proper substitute. But surely while these bonds are outstanding they ought to be accepted as security for their face value. This alone would check the retirement of bank notes and probably increase their issue. And yet it is those who demand "more money" that resist so plain a remedy. ---[Because more of this private money is more debt and more bondage.]

And there is still another measure of relief against a contraction of the currency. Under the present law national banks, compelled by the payment of their bonds to retire their circulation, must deposit in the Treasury notes equal in amount to the bank notes to be retired. The United States then assumes the payment of the bank notes when presented, but, as the law now stands, must retain the United States notes held in the Treasury for that purpose. This is a direct and immediate contraction of the currency. To avoid this I propose that these United States notes shall be covered into the Treasury, but be paid out on the public debt or for other purposes, and thus be restored to circulation. The bank notes will continue in circulation until presented to the Treasury for redemption. They will become in legal effect United States notes and will only be presented for payment when unfit for use. The same process will apply to the remaining bank circulation when and as it is surrendered by the banks.

These two measures will be effective to stop the contraction of the currency. This would delay and postpone the further retirement of bank currency until 1907, when the policy of basing Treasury notes upon gold and silver bullion will be proven to be either a success or a failure. If Senators really desire to secure more money, good money, based upon gold and silver coin and bullion, they can secure it without the hazard of the dangerous experiment of the free coinage of silver and of detaching the United States from the standards of value recognized by the principal commercial, civilized, and christian nations of the world.

I have thus stated my view of the best mode to provide for a gradual increase of money for circulation and to provide a substitute for national-bank notes retired when and as the bonds of the United States are retired.

And now, Mr. President, I come to the second object of desire, to increase the market value of silver, not only in the United States, but in the world, in the belief that this is essential to the success of any measure proposed and in the hope that our efforts will advance silver to its legal ratio with gold and induce the great commercial nations to join with us in maintaining the legal parity of the two metals or in agreeing with us in a new ratio of their relative value. To decide how this can be done we must know the precise legal status of silver, how it was affected by the acts of 1834 and 1853 and the coinage act of 1873. After the suspension of the coinage of the silver dollar in 1805, fractional silver coins and also gold coins were issued from the mints; but as gold, by being undervalued, was drawn from our country, fractional silver and foreign coin were the only coin in circulation. One ounce of gold was worth more than 15 ounces of silver, and therefore gold went to countries where it would buy 15½ ounces of silver. To avoid this and to invite gold to our country, the acts of 1834 and 1837 changed the ratio so that 1 ounce of gold was rated at 16 ounces of silver. This was a mistake in the opposite direction, for 16 ounces of silver were worth more in Europe than 1 ounce of gold, and silver disappeared from the United States and gold became our only coin.

To meet this difficulty and to secure the use of both metals, Congress, by the act of 1853, following the example of England, provided for a coinage of fractional silver containing less grains of silver and a legal tender for only $5, and thus silver and gold --gold as the standard and silver as subsidiary-- were the coin of our country. The silver dollar had disappeared long years before. None were to be found except as curiosities. Only $8,045,838 had been coined from 1793 up to 1873, or less than three months' coinage under the present law. Under these conditions we entered upon the civil war, when gold and silver alike disappeared from our currency. Paper money alone, from the 1 cent stamp to the $5,000 United States note, was then our domestic currency. We exacted gold for duties on imported goods to enable us to maintain the credit of our bonds. It did not circulate, but was a commodity at a premium for seventeen years until resumption. We heard nothing in Congress of coinage until the abortive effort to devise an international coin as a medium of exchanges between nations, a gold coin that would be the exact equivalent of £1, or $5, or 25 francs.

This was at the Paris conference in 1867, and my letter in support of it was quoted in this debate. I stand by that letter, every word of it. At that time it expressed the almost universal desire of our people, it was approved by the Paris conference, and would have been adopted by the leading commercial nations but for the refusal of Great Britain to make the slight change requisite in her pound sterling. It is now the hope and expectation of the leading scientists of the world and will be the first step of the first successful international monetary conference --an international coin which will contain so many grains of gold and be the exact equivalent of 25 francs, $5, £1, so that with this international coin a man may travel everywhere. That was only defeated by the narrow idea of the British Government, who refused to change their pound sterling in intrinsic value from 484 to 479 and a fraction, and they declined to do it. It did not deal with or affect the silver question at all.

The next we heard of coins and coinage was in a report from the Secretary of the Treasury on the 25th of April, 1870, transmitting the bill now known as the coinage act of February 12, 1873, which is here before me. This bill was, on its face, a revision of all the laws relating to the Mint and coinage of the United States. It stated what coins of gold and silver and what minor coins should be coined, and of what metal composed. It dropped from the coins of the United States the silver dollar of 412½ grains. And now we are told that this coin was surreptitiously dropped, that a conspiracy existed to deprive the country of one-half of its money with a view to increase the value ot the remainder.

I mean now to place upon the Record proofs so absolutely conclusive that this is a false cry, that if any man hereafter repeats it in the Senate and the House the evidence of the falsehood will stare him in the face.

What was the silver dollar that was said to be demonetized surreptitiously by this act ? To some men it is a kind of fetich, made an object of superstitious worship which it is sacrilegious to disturb. It was a coin authorized by the act of April 2, 1792, containing 416 grains of standard silver, afterwards reduced to 412½ or 371¼ grains of pure silver. It was based upon the ratio of 15 to 1, admitted from the beginning to be incorrect. There were coined of these dollars prior to 1805 1,439,517, or about one-half of one month's coinage of the silver dollar now. President Jefferson then suspended their coinage. Mr. Campbell P. White, in an appendix to his famous report, upon which the act of 1834 was founded, transmits a letter from Samuel Moore, Director of the Mint at Philadelphia, under date of May 25, 1832, in which he says:

The President, in 1805, interposed more efficiently by directing that the coinage of dollars should be suspended at the Mint; this remedy met the particular exigence. The Chinese, through prejudice, undervalued the dollar; the lower denominations they refused.

Mr. J.K. Upton, in his book, Money in Politics, says:

The silver was now (1805) the unquestioned unit of account, and in this coin all contracts calling for dollars could be satisfied. Mr. Jefferson, who was then President, had favorably indorsed the ratio of 1 to 15 proposed by Mr. Hamilton and adopted in the coinage act of 1792. He believed that both metals could and would circulate side by side under the relations fixed by that act. He desired that gold should circulate as well as silver, and, to prevent the expulsion of gold, he peremptorily ordered the Mint to discontinue the coinage of the silver dollar, and Congress and the country seemed to have approved his action, although taken without authority, if not in direct violation, of law. To the effect of this executive interference is probably due the fact that from 1806 to 1836 no silver dollars were coined.

So this dollar so anxiously sought for was demonetized by Mr. Jefferson, who was familiar with the history of its coinage, and that continued practically until our civil war, as I shall presently show. Not one dollar of this coin was issued from its suspension by Mr. Jefferson until after the passage of the act of 1834, and only $1,300 prior to 1840. From that time until the approach of the civil war the issue was comparatively insignificant, varying yearly from $1,100 to $184,000, the highest amount in any one year. Yet during this period, from 1805 to 1860, over $100,000,000 of fractional silver coins were issued and in circulation, all of which was demonetized in the general sense from 1834, being a legal tender for only $5. The silver dollar had fallen into desuetude. As the war approached and until 1873, about 5,000,000 silver dollars were coined, solely for exportation to China and Japan, but none of them entered into circulation. Many of us never, prior to 1878, saw a silver dollar. It was an image of the past, lost to sight and memory, conceived by Hamilton, suspended by Jefferson, and ignored by two generations except as a convenience for the exportation of silver bullion.

Mr. Jones, of Nevada. Mr. President---

The Presiding Officer (Mr. Harris in the chair). Does the Senator from Ohio yield to the Senator from Nevada ?

Mr. Jones, of Nevada. Allow me to say one word.

Mr. Sherman. Certainly.

Mr. Jones, of Nevada. I have not known that those who advocated the recoinage of silver insist that a particular species of coin shall be coined at the mint. I ask the Senator how many gold dollars have been coined ?

Mr. Sherman. I have given the amount of gold.

Mr. Jones, of Nevada. But I ask him to state the amount of gold dollars, not the amount of ten-dollar pieces. I want to say right here that up to and including 1846 there was more full legal-tender silver money coined than gold, and that it was not the silver dollar that the silver men were insisting upon coining, but silver money with full legal-tender functions, whether in the form of half-dollars or quarter-dollars or any other kind of silver coin; that it was half-dollars, the more convenient coin, that were coined, and not the dollar piece. It is of no consequence whether it was a dollar piece or a half-dollar piece that was coined.

Mr. Sherman. I will come to that in a moment. The half-dollar was never coined except as a subsidiary coin and it was only a legal tender for $1. The half-dollar since 1853 has only been a legal tender for $1.

Mr. Jones, of Nevada. I am speaking of the fact that from the foundation of the Government up to and including 1846 more legal-tender silver money was coined than gold in this country.

Mr. Mitchell. Will the Senator allow me just one moment ?

Mr. Sherman. I will say, as I said to the Senator from Colorado, that I do not like to refuse and I do not like to consent.

Mr. Mitchell. I only want to occupy one moment.

The Presiding Officer. Does the Senator from Ohio yield ?

Mr. Sherman. I will hear the Senator from Oregon.

Mr. Mitchell. I think a false impression has been given generally as to the action of Thomas Jefferson, referred to by the Senator from Ohio. There was not a general suspension of silver coinage, only the silver dollar, not the suspension of silver entirely. The Senator surely does not mean to convey the impression that Jefferson's action related to anything more than the suspension of the coinage of the silver dollar, not to the half dollars or any other silver ?

Mr. Sherman. The dollar I am talking about altogether.

Mr. Mitchell. And the other coins were all legal tender ?

Mr. Sherman. I am talking about the dollar of the fathers. I will repeat the sentence that was broken by the interruption of my friend from Nevada. This policy was an image of the past, lost to sight and memory, conceived by Hamilton, suspended by Jefferson, and ignored by two generations except as a convenience for the exportation of silver bullion.

No wonder that the Senator from Nevada did not know that the silver dollar was demonetized. The wonder is that he knew of its existence. The revisers of the United States statutes were oblivious to it, for, while the act of 1873 dropped it from coinage and forbade its issue from the mints, that act did not take from the silver dollars, if in existence, their legal-tender quality. While the whole mass of fractional silver coins issued under the act of 1853 had been for nineteen years a legal tender only for $5, the silver dollar was among the people an unknown coin.

But it is not the legal qualities of the silver dollar I have to deal with, but it is the imputation that it was dropped from our coinage surreptitiously, done by stealth, unlawfully; this is the charge that I repel. I was chairman of the Committee on Finance when the act of 1873 was considered and passed. My associates in 1871 were Senators Justin Morrill, George Williams, Alexander Cattell, Willard Warner, Reuben Fenton, and Thomas Bayard. The Committee on Coinage of the House, having charge of the bill, consisted of Messrs. William Kelley, Samuel Hooper, John Hill, Noah Davis, Peter Strader, and John Griswold. What motive could we have for such a cowardly, disgraceful proceeding ? On the 25th of April 1870, when the bill was sent to us by the Secretary of the Treasury, the silver dollar was worth $1.0312 in gold in the markets of the world. This was before Germany had sold her silver and adopted the gold standard, before the slightest sign of the depreciation of silver. Could we so far foresee the future ?

But I will not leave this matter to argument or inference. The bill on its face shows that it was a bill revising all the laws relating to mints and coinage. In the bill sent to us on the 25th of April, 1870, the silver dollar was omitted and its further issue prohibited. Here is a copy of the bill sent to us with the report. [Exhibiting.] I will read the fifteenth section. The fourteenth section provides the weight of the double eagle, etc., giving the weight of the gold coins. The fifteenth section was as follows:

Sec. 15. And be it further enacted, That of the silver coins, the weight of the half dollar, or piece of fifty cents, shall be one hundred and ninety-two grains; and that of the quarter dollar and dime, shall be, respectively, one-half and one-fifth of the weight of said half dollar. That the silver coin issued in conformity with the above section shall be a legal tender in any one payment of debts for all sums less than one dollar.

That is, "for all sums less than $1." Then here is section 18, just following it:

Sec. 18. And be it further enacted, That no coins, either of gold, silver, or minor coinage, shall hereafter be issued from the mint other than those of the denominations, standards, and weights herein set forth.

Not only was the silver dollar omitted, but there was an express provision that no other coin except those mentioned should be issued from the mint. So not only were the names of the coins designated, their weight and measure fixed, but all others were prohibited by the law of 1873 and on the face of the bill. That bill was sent to us here at the time when the silver dollar was demonetized. With the letter of the Secretary of the 25th of April, 1870, Mr. Knox, under a conspicuous, large-typed heading --"silver dollar; its discontinuance as a standard"-- says:

The coinage of the silver-dollar piece, the history of which is here given, is discontinued in the proposed bill. It is by law the dollar unit, and, assuming the value of gold to be fifteen and one-half times that of silver, being about the mean ratio for the past six years, is worth in gold a premium of about 3 per cent. (its value being $1.0312), and intrinsically more than 7 per cent. premium in our other silver coins, its value thus being $1.0742. The present laws consequently authorize both a gold-dollar unit and a silver-dollar unit, differing from each other in intrinsic value. The present gold-dollar piece is made the dollar unit in the proposed bill, and the silver-dollar piece is discontinued.

What can be clearer than that ? That message was sent to us.

Mr. Dawes. Did that accompany the bill ?

Mr. Sherman. Certainly. Here is the document.

If, however, such a coin is authorized, it should be issued only as a commercial dollar, not as a standard unit of account, and of the exact value of a Mexican dollar, which is the favorite for circulation in China and Japan and other Oriental countries.

This bill was not acted upon in the Senate until the next session of Congress. In the mean time a copy of it was sent to all the experts in the United States. The bill sent to them included among the silver coins a dollar of 384 grains instead of the old dollar of 412½ grains, thus not only dropping out the old dollar, but substituting a token dollar not a legal tender. The replies were sent to the House of Representatives in obedience to a resolution of the House on the 25th of June, 1870.

I have, then, here before me a voluminous report of Mr. Boutwell, the Secretary of the Treasury, of 100 printed pages. It contains a full statement of the objects of the bill, the necessity for the proposed revision, with reports, among others, from Robert Patterson, F. Peale, H.R. Linderman, James Ross Snowden, G.F. Dunning, and E.B. Elliot, all of them known as scientific experts and the principal officers of the mints and assay offices. Each of them discussed the provisions of the bill.

The necessity for the revision of the coinage law was admitted on all hands. It had been recommended by Secretary Chase and his assistant, Mr. Harrington, by Secretary McCulloch and his assistant, Mr. Chandler, now a member of the Senate. There had been no codification of the mint laws for thirty-five years. The different acts of Congress in reference to the service were scattered through all the various volumes of the statutes. The English Government had recently revised its mint laws, introducing important reforms. The "coinage act of 1873" was framed with a like purpose. The operations of the Mint were not suspended during the war.

The amount of coinage during the suspension of specie payments, 1861-1879, was $735,320,317, while the total coinage from 1792, the year of the establishment of the Mint, to 1861, a period of seventy years, was but $599,428,229. There was 50 per cent. more coined in the eighteen years after 1861 than during the whole period of the Government before 1861. The business of the Mint was rapidly increasing and the wisdom of creating a bureau of the mint in the Treasury Department was apparent to every one.

The section of the bill which discontinues the coinage of the old silver dollar was discussed by all the experts. Hon. James Pollock, formerly governor of Pennsylvania, then Director of the Mint, favored the reduction of the weight of the silver dollar from 412½ grains to 384 grains, as he had previously recommended in his annual report of 1861. Robert Patterson was in favor of the abolishment of the silver dollar, half-dime, and three-cent piece. He said: "Gold becomes the standard of which the gold dollar is the unit. Silver is subsidiary, embracing coins from the dime to half-dollar." The heading of this paragraph was printed in capital letters, thus: "silver dollar, half-dime, and three-cent piece discontinued, and coins less than dime of copper, nickel, legal tender -- one-cent piece of one gram in weight."

The same report contains a letter dated June 10, 1870, from E.B. Elliot, late Actuary of the Treasury Department (page 70), well known to many Senators, now dead, which gives a brief history of the silver dollar, headed as follows, in capital letters:

The Standard Silver Dollar -- Its Discontinuance as a Standard.

The bill proposes the discontinuance of the silver dollar, and the report which accompanies the bill suggests the substitution for the existing standard silver dollar of a trade coin of intrinsic value equivalent to the Mexican silver piastre or dollar.

Franklin Peale, formerly melter and refiner of the Mint at Philadelphia, says:

To designate what the weight of silver coinage should be at this time is a difficult problem, and should be carefully considered by competent financiers, bullionists, and Mint officers before any law is enacted.

The heading of this paragraph was in capital letters, as follows: "Weight of silver coin should be carefully considered."

Mr. Peale recommended the discontinuance of the coinage of the one-dollar and three-dollar gold pieces and gave his reasons therefor.

Dr. H.R. Linderman, formerly Director of the Mint, discussed the subject in a paragraph which was headed in capitals as follows: "discontinuance of silver dollar."

Hon. James Ross Snowden discussed the same subject in a paragraph which was headed in capitals as follows: "the present silver dollar should not be discontinued."

Hon. George F. Dunning, late superintendent of the assay office in New York, the officers of the United States mint at San Francisco, and others discussed this feature of the bill. It was well said in the report of the Comptroller of the Currency in 1876:

If the question of the double standard did not become prominent in the discussion of the bill it was for the reason that usage had established the gold dollar as the unit, the silver dollar, on account of its greater relative value, having, with the Mexican dollar and pistareen, disappeared from the circulation of the country. The coinage act of 1873 simply registered in the form of a statute what had been really the unwritten law of the land for forty years.

We had this one-hundred-page document sent by Secretary Boutwell, with returns from all the officers of the Mint and the experts throughout the country, probably thirty or forty of them. We had at that time, when we considered the bill, the previous letter of our Deputy Comptroller of the Currency, who had charge of the Mint, recommending the passage of the bill, with a copy of the bill, and copies of the bill were sent broadcast, omitting entirely the silver dollar and calling special attention to that omission in every possible way.

Now, Mr. President, with all this copious information in both Houses, this coinage bill was reported to the Senate by the Committee on Finance on the 19th of December, 1870. On the 9th and 10th days of January, 1871, it was debated for two full days, mainly upon the coinage charge of three-tenths of 1 per cent., by Senators Cole, Williams, Corbett, STEWART, and Casserly against the charge, and MORRILL and SHERMAN for it. The bill was read in full, and a number of amendments made, but the coinage provision was defeated and the charge for coinage was repealed.

The bill passed by a vote of 36 yeas and 14 nays, January 10, 1871. Among the nays I find the names of MORRILL and SHERMAN, no doubt because against their advice all coinage charges were repealed. Among the yeas I find the names of Casserly, Cole, Corbett, Nye, STEWART, and Williams, every Senator from the Pacific coast. It was that bill that omitted and excluded the silver dollar from our coinage, and, in accordance with the act of 1853, continued all silver coinage as subsidiary and a legal tender for $5 only. No bill was ever more broadly proclaimed or publicly discussed in all its details than this, and yet my venerable friend [Mr. Morrill] and myself, who voted against the bill, have been singled out and named as dupes or comparators, while gentlemen who voted for the bill were victims of a plot, ignorant of its provisions, and generally taken in ! It is better far to stand manfully for what we did honestly, even if we were mistaken, which to this hour I do not think we were. Is it possible that any man who participated in this debate could have been ignorant that the old silver dollar of 1792 was dropped from our coinage by this bill ? Is it not more likely that he was indifferent to it or had forgotten it ? I knew and recall the dropping out of the silver dollar, and neither plead ignorance nor negligence, but I had not the omniscient power to see into the future, when the dollar suspended by Jefferson, demonetized by Jackson and Benton, superseded by subsidiary half-dollars by Pierce and Hunter, turned into a trade-dollar in 1873, would become the idol of the Democratic party in 1890, as the best expedient for cheap money, the most plausible pretext for confiscating a portion of public and private debts.

This bill was sent to the House, referred to the Committee on Coinage, and reported favorably, but no action was taken upon it during that session. Early in the called session following Mr. Kelley introduced an original bill substantially similar to the bill of the preceding Congress, but with this important modification of section 16. The House bill recommended a subsidiary dollar of 384 grains with limited legal tender in place of the old dollar of 412½ grains. So the other House had inserted in the bill when it was reintroduced by Mr. Kelley this subsidiary coin of 385 grains', containing 26½ fewer grains than the old silver dollar, and made subsidiary coin like the former subsidiary coin of half-dollars and quarter-dollars.

The bill finally became a law on the 12th of February, 1873, nearly three years after it was introduced into Congress. It was reprinted thirteen times and extra copies were printed for circulation. It was conned over, amended, and debated almost as copiously as the bill now pending, and no man in either House proposed to retain the old silver dollar. It was not mentioned, it was not thought of. It was an afterdevice. The fact that it was omitted from our coins was referred to in debate in both Houses. Mr. Hooper, in the House of Representatives, said:

Section sixteen reŽnacts the provisions of existing laws defining the silver coins and their weights respectively, except in relation to the silver dollar, which is reduced in weight from four hundred and twelve and a half to three hundred and eighty-four grains; thus making it a subsidiary coin in harmony with the silver coins of less denomination, to secure its concurrent circulation with them. The silver dollar of four hundred and twelve and a half grains, by reason of its bullion or intrinsic value being greater than its nominal value, long since ceased to be a coin of circulation, and is melted by manufacturers of silverware. It does not circulate now in commercial transactions with any country, and the convenience of those manufacturers in this respect can better be met by supplying small stamped bars of the same standard, avoiding the useless expense of coining the dollar for that purpose. The coinage of the half dime is discontinued for the reason that its place is supplied by the copper-nickel five-cent piece, of which a large issue has been made, and which, by the provisions of the act authorizing its issue, is redeemable in United States currency.

Here it was pointed out by Mr. Hooper, a very distinguished financier, as we know, that it was not only proposed to drop the old dollar, but to substitute a dollar containing 26½ grains less than the old dollar, and that was adopted by the House. Mr. Stoughton and Mr. Potter, both leading members, supported the proposition. Mr. Kelley, whose honorable life we have recently commended, advocated the single standard of gold:

Mr. Kelley. I wish to ask the gentleman who has just spoken [Mr. Potter] if he knows of any Government in the world which makes its subsidiary coinage of full value ? The silver coin of England is ten per cent. below the value of gold coin. And acting under the advice of the experts of this country, and of England and France, Japan has made her silver coinage within the last year twelve per cent. below the value of gold coin, and for this reason: it is impossible to retain the double standard. The values of gold and silver continually fluctuate. You cannot determine this year what will be the relative values of gold and silver next year. They were fifteen to one a short time ago; they are, sixteen to one now.

Hence all experience has shown that you must have one standard coin, which shall be a legal tender for all others, and then you may promote your domestic convenience by having a subsidiary coinage of silver, which shall circulate in all parts of your country as legal tender for a limited amount, and be redeemable at its face value by your Government.

So it appears that these honorable gentleman not only knew what they were about, but gave their reasons for adopting the 384-grain dollar instead of the old dollar of 412½ grains, and the House acted with full knowledge in adopting the French dollar and made it a subsidiary coin or a legal tender for but $5. When the House bill came to the Senate it contained the silver dollar of 384 grains, and also fractional coins of the same relative value, precisely in accordance with the coins of 1853, except that the 384-grain dollar, made a legal tender for only $5, was substituted for the old silver dollar of 412½ grains, which was a full legal tender. This, it appears, was explained by me on the 17th of January, 1873, in the following words:

Mr. Sherman. This bill proposes a silver coinage exactly the same as the French, and what are called the associated nations of Europe, who have adopted the international standard of silver coinage; that is, the dollar provided for by this bill is the precise equivalent of the five-franc piece. It contains the same number of grams of silver; and we have adopted the international gram instead of the grain for the standard of our silver coinage. The "trade dollar" has been adopted mainly for the benefit of the people of California, and others engaged in trade with China. That is the only coin measured by the grain instead of by the gram. The intrinsic value of each is to be stamped upon the coin.---[ The Sherman is lying now, and he lied on January 17, 1873, to Senator Casserly. Sherman gave above response to the objection raised by Casserly regarding section 18 of the bill, omitting the eagle from the gold dollar and the silver dollar. By this time --and Sherman was the very few who knew this-- the $1 silver coin was omitted from among the coins of the United States, in section 15. Why did Sherman lie to Casserly ? We know why he is lying now. If Casserly had been aware that there is no $1 silver coin, would he ask to put an image of an eagle on it ? If Casserly objected to the omission of the eagle, would he not have objected to the omission of the whole-entire silver dollar ?]

Now, unless some Senator, then a member of this body, did not know the difference between a five-franc piece and a dollar, he certainly must not have been listening to me or he would have been clearly informed:

It contains the same number of grams of silver; and we have adopted the international gram instead of the grain for the standard of our silver coinage. The "trade dollar" has been adopted mainly for the benefit of the people of California, and others engaged in trade with China.

I presented a petition here from the Legislature of California asking us to give them a dollar more valuable than the Mexican coin, in order that they might have a convenient mode of transporting their silver bullion, then not used at all among the people of the United States as currency.

That is the only coin measured by the grain instead of by the gram. The intrinsic value of each is to be stamped upon the coin.

Afterwards Mr. Casserly said that a dollar somewhat more valuable than the Mexican dollar would be a convenient coin for the exportation of silver in the Chinese trade; and he produced a memorial from the Legislature of California asking Congress to provide for such a coin, and we did provide for the trade-dollar of 420 grains, to be coined at any mint at the expense of the owner of the bullion. Other amendments were made and the bill passed.

---[What petition, what memorial ? The Record of January 17, 1873, does not show either. The record does not show that the Senate acted on the trade-dollar at all. Why, and by what right, would the conference committee insert that trade-dollar and remove the 384-grain silver coin ?]A conference was ordered on the disagreeing votes of the two Houses and was held. The House conferees agreed to the amendment in respect to the trade-dollar and provided "that any owner of silver bullion may deposit the same at any mint to be formed into bars or into dollars of the weight of 420 grains troy, designated in this act as trade-dollars." This dollar took the place of the 384-grain dollar. The report was signed by the conferees of both Houses, John Sherman, John Scott, T.F. Bayard, managers on the part of the Senate, and Samuel Hooper and W.L. Stoughton, managers on the part of the House. The report was read in the Senate February 6 and in the House February 7, 1873, and agreed to.

I do not see how a member of either House, in the face of the recommendation of the Treasury Department and of the debate in both Houses on this very question, can repeat the imputation against the living and the dead of secretly and surreptitiously demonetizing the silver dollar without confessing to a grave neglect of public duty or a want of common intelligence. When this matter was discussed here in March, 1888, by the lamented Senator from Kentucky, Mr. Beck, he repeated the stale charge that the old silver dollar was surreptitiously dropped from our coinage, and I promptly replied in a speech I hold in my hand. I produced the original bills from the files of the Senate. I produced the memorial of the Legislature of California and conclusively answered this charge, not only for myself, but for every member of the Senate and House of Representatives that passed that bill, and, I am glad to say, to the entire satisfaction of the then Senator from Kentucky.

And now, sir, I intend to add the testimony of one more witness, that of Hon. Abram S. Hewitt of New York [Peter Cooper's son-in-law], who gave to this subject the most careful study. He said in his speech in the House of Representatives on the 5th of August, 1876, as follows:

The gentleman from Missouri [Mr. Bland] on the 3d instant stated that the coinage act of 1873 "was passed surreptitiously and without discussion, and was one of the grossest measures of injustice ever inflicted upon any people." The honorable Senator from Nevada [Mr. Jones] and the honorable gentleman from Indiana [Mr. Holman] have made similar statements, and these statements have been reiterated by the press of the country and repeated again to-day by the gentleman from Missouri [Mr. Bland] and the gentleman from Illinois, [Mr. Fort.] In answer to these charges I propose, at the risk of being tedious, but in order to refute them once for all, to give, in a note at the end of my remarks, the history of the coinage act of 1873, as shown by the records of the Treasury Department and of Congress.

I have felt it necessary to make this weary statement in order to prove that the legislation of 1873 was not surreptitiously enacted, traveling over ground that has been occupied in part by other members who have addressed the House, and in part by the daily press, because there is nothing so unpalatable to the American people as "tricks" in legislation, of which the Committee on Mines and Mining will be fully conscious when it comes to be generally understood how far they have exceeded the legitimate line of their duty in bringing forward this bill, which could never have been reported from the Committee on Banking and Currency, to which it properly belonged.

I will ask the Reporter to insert at the end of my remarks the historical statement of the coinage act of 1873, prepared by this gentleman, and I will not weary the Senate by reading it. It contains a most complete analysis and statement of every stage of the passage of the bill.

Now, sir, I shall leave this question, upon which perhaps I show a little more feeling than I ought. It is pretty hard to chase down a lie so often repeated, but I thought it necessary to do it, and set forth the matter here, not only for myself, but also for all others engaged in that legislation.

If, after this second vindication of the members of the Forty-second Congress, this baseless charge is repeated I shall content myself with denouncing it as a falsehood.

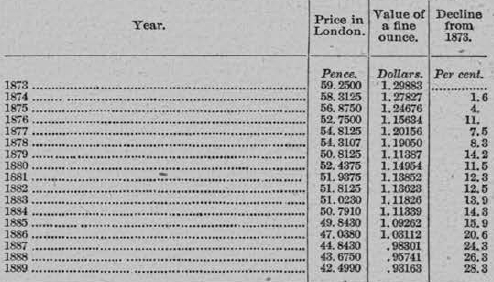

And now, sir, I recur to my second proposition, how to increase, if possible, the market value of silver to its legal ratio to gold, that of 16 to 1. In 1878 the United States commenced the experiment under the act of February 28, 1878, by remonetizing the silver dollar of 412½ grains of standard silver and by purchasing silver bullion at the market price to the amount of $2,000,000 worth a month and coining it into silver dollars. We know the result of that experiment. Silver bullion steadily declined in value. This table gives the average price of silver in London each fiscal year, 1873-1889, and the value of an ounce of fine silver at par of exchange, with decline expressed in percentages, each year since 1873:

The silver dollar, though a full legal tender, with every effort made by successive Secretaries of the Treasury, could not be kept in circulation to an amount exceeding $60,000,000. When pressed into circulation it steadily returned to the Treasury, and on June 1 the amount in circulation was $513,348,174 and the amount in the Treasury was $309,988,092. But the certificates based upon the dollars were issued and readily circulated as money and now form nearly one-third of all the paper circulation in the country and are received and paid out on a parity with United States notes and gold coin. This experiment clearly establishes two things: One is that silver dollars can not be made to circulate as money in excess of a very moderate amount for change or in small transactions. The other is that the coinage of silver dollars does not tend to advance the price of silver in the markets of the world.

But it is said that the reason of this failure is that executive officers neglected or refused to exercise the discretionary powers given them to buy and coin bullion to the extent of $4,000,000 per month. There is no ground for this contention. If the coinage of $2,000,000 worth of silver did not check the fall of silver, but steadily accelerated its fall, what would have been the natural effect of the coinage of $4,000,000 ? The very presence of $290,000,000 of silver coin known to be in our Treasury vaults that can at will be dumped upon the markets of the world is the great bearish fact, the menace that tends to depreciate the price of silver. If this great sum had been scattered among the hordes of Asia, where it is largely used as ornaments and where it is the only standard of value, it would be mingled in the vast unknown mass of three thousand millions of silver estimated as existing in the world.

But we have made this impossible. We have been careful to buy silver bullion in the market at about $1 for an ounce of 480 grains and have coined 371 grains of this silver and called it a dollar. We have given to this dollar, when circulated at home, certain qualities which make it current here as a dollar, but it is not current anywhere else in the world. All other nations can buy silver bullion as cheap as the United States and coin it for less cost. This bullion is an ample security for its cost, and if represented by notes not greater in amount than the cost of the bullion they can easily be kept in circulation, but the coin can not be. Its forced circulation would depreciate it in every State in the Union, especially in California and Nevada, where a large proportion of contracts are payable in gold.

As coin in the vaults of the Treasury it is in far more danger from thieves; it is more expensive to handle and to guard than bullion, ton for ton. It is easily counterfeited or duplicated. It is a vast hoard always in sight, known to all men, increasing yearly. Suppose instead of $290,000,000 it was $580,000,000, would this tend to increase its value ? Our silver in the form of coin does not and can not circulate in any country but our own. It is of less value in any foreign country than bullion, for to be coined there it must be converted into bullion. It is the opinion of many wise men that if the United States had only coined as much silver as could be circulated at home, leaving the surplus to find its natural market as bullion, the price of it would not have receded to the rate at which it has been sold; but, be this as it may, its continued coinage when not needed as money is not only a useless expense, but tends to lower the price of bullion.

What then can we do to arrest the fall of silver and to advance its market value ? I know of but two expedients. One is to purchase bullion in large quantities as the basis and security of Treasury notes, as proposed by this bill. The other is to adopt the single standard of silver and take the chances for its rise or fall in the markets of the world. I have already stated the probable results of the boarding of bullion. By purchasing in the open market our domestic production of silver and hoarding it in the Treasury we withdraw so much from the supply of the world, and thus maintain or increase the price of the remaining silver production of the world. It is not idle in our vaults, but is represented by certificates in active circulation. Sixteen ounces of silver bullion may not be worth 1 ounce of gold, still $1 worth of silver bullion is worth $1 worth of gold.

What will be the effect of the free coinage of silver ? It is said that it will at once advance silver to par with gold at the ratio of 16 to 1. I deny it. The attempt will bring us to the single standard of the cheaper metal. When we advertise that we will buy all the silver of the world at that ratio and pay in Treasury notes, our notes will have the precise value of 371¼ grains of pure silver, but the silver will have no higher value in the markets of the world. If, now, that amount of silver can be purchased at 80 cents, then gold will be worth $1.25 in the new standard. Free coinage means the substitution of a cheaper standard. All labor, property, and commodities will advance in nominal value, but their purchasing power in other commodities will not increase. If you make the yard 30 inches long instead of 36 you must purchase more yards for a coat or a dress, but do not lessen the cost of the coat or the dress. You may, by free coinage, by a species of confiscation, reduce the burden of a debt, but you can not change the relative value of gold or silver or any object of human desire. The only result is to demonetize gold and to cause it to be hoarded or exported. The cheaper metal fills the channels of circulation and the dearer metal commands a premium.

If experience is needed to prove so plain an axiom we have it in our own history. At the beginning of our National Government we fixed the value of gold and silver as 1 to 15. Gold was undervalued and fled the country to where an ounce of gold was worth 15½ ounces of silver. Congress, in 1834, endeavored to rectify this by making the ratio 1 to 16, but by this silver was undervalued. Sixteen ounces of silver were worth more than 1 ounce of gold and silver disappeared. Congress, in 1853, adopted another expedient to secure the value of both metals as money. By this expedient gold is the standard and silver the subsidiary coin, containing confessedly silver of less value in the market than the gold coin, but maintained at the parity of gold coin by the Government.

The bill was carried forward in the Senate Chamber by Mr. Hunter, of Virginia, and many of the most distinguished men of that day participated in the debate upon it, where it was fully discussed and its passage put upon the ground that it was impossible to make the two metals always equal to each other so that their relative value would not change. Therefore, gold was adopted as the standard and silver was to be used so far as it could be as a subsidiary coin for currency. In that way both metals have run side by side from that day to this, and under that law more gold and silver coin --four-fold more of both metals-- has been coined than under the old system of up Jo and down Jack, the system of a changeable ratio.

This system has been maintained now for thirty-six years, more than an average lifetime. Under it the coinage of silver has enormously increased. From 1792 to 1853 the entire coinage of silver was $79,241,904.50, including $2,506,890 of standard silver dollars. From 1853 to 1873, when the coinage act was passed, the coinage of silver dollars was $5,538,948, and of fractional silver (subsidiary) was $60,361,032.10. Under the act of 1873 there were issued 35,965,924 trade dollars, and $5,445,264.40 fractional silver. Under the resumption act of 1875, there was coined of fractional silver $48,082,580. Under the act of 1878 there were coined of standard silver dollars $363,626,266, as shown by the following table:

It is a remarkable fact that since 1853, when all silver coin was made from bullion bought by the Government, the coinage and use of silver has been much greater than when the coinage of silver was free. Under the free-coinage system prior to 1853 we coined in silver $79,241,904.50, and under coinage limited to bullion bought by the Government we coined in silver $519,020,014.55. Under the present system we have also maintained an increasing coinage of gold and have now in the United States among the people or in the vaults of the Treasury $689,275,007 in gold coin or bullion, all of which is either circulating as money or is the basis of paper money in active circulation.

Under the free-coinage system the cheaper metal was the only money of the country; the other fled to foreign countries. A rise or fall of 3 per cent. would demonetize one or other of the metals. Under the present system the people are indifferent to the fluctuations in the bullion market and they know they have a fixed standard of value and that the Government, the custodian of their money, will maintain the parity of the purchasing power of their coins whatever may be the market value of the metal contained in them.

The gold standard has been the recognized policy of all the great political parties that have longest controlled the Government of the United States. The Federal party in the beginning sought to secure it by ascertaining the precise relative market value of the two metals and coining both as money, but erroneously fixed the ratio at 15 to 1. When the Democratic party came into power, Mr. Jefferson, to secure the circulation of gold, suspended the coinage of the silver dollar, but a faulty ratio stood in his way. General Jackson and Benton and their associates in 1834, with the avowed purpose to restore gold, or "Benton mint drops," as they were called, to circulation, changed the ratio to 16 to 1, but this banished all silver coin. In the administration of President Pierce in 1853 the present system was adopted, by which gold became the unit of value and the coinage of silver was made subsidiary, but was always maintained in purchasing power the equal of gold, dollar for dollar.

And so when the Republican party came into power, though driven by the stress of war to the almost exclusive use of credit money, yet as soon as possible it resorted to the policy of 1853, of gold as the unit and silver as subsidiary, and coined both metals in greater sums than ever before, and maintained their parity by a limitation of the coinage of the cheaper metal and its prompt redemption by being received at its legal ratio into the Treasury as the equivalent of gold. By this policy it has combined in use within twelve years over $800,000,000 of gold and silver coin, and with ample reserves of their coin in the Treasury now keeps in active circulation over $900,000,000 of paper money, which is in our own country and in all parts of the world received and paid out as the equivalent of gold or silver coin.

The adoption of free coinage now will be a reversal of the established policy of the Government from its beginning. It will limit our coinage to a single metal, for who will deposit gold for coinage into dollars when it is worth more in the markets of the world ? If a fluctuation of 3 per cent. drove gold and silver alternately from our country, how much more would a fluctuation of 20 or 30 per cent.?